Stand-up comedian Tony Campanelli confessed Monday to the Feb. 26 killing of 180 comedy-club patrons during a performance at Crack-Ups in Royal Oak. . . . “Man, I killed ’em,” the 33-year-old Campanelli told Royal Oak police interrogators. “You shoulda seen them rolling out there. I really knocked ’em dead. . . .” —The Onion, March 1, 2000

“These Are the Poems, Folks”: On the Relationship Between Poetry and Joke-telling by David Yezzi

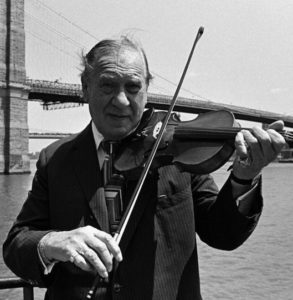

![]() once heard the actor F. Murray Abraham bemoan the fact that, after his Academy Award–winning turn as Salieri in Amadeus, he was, for years, straitjacketed into serious roles and that, in fact, he was very funny.1 (Abraham had played Bottom to great acclaim at Joseph Papp’s Public Theater in New York, after all.) He then told this joke—one of his favorites, he said. It goes like this: A man says to his doctor, “Doctor, I think my wife is going deaf, but I don’t know how bad it is. What should I do?” The doctor says, “Well, when she’s turned away from you, call out her name and if she doesn’t respond move closer until she hears you. Then you’ll know how deaf she is.” So, the man goes home, sees his wife at the kitchen sink with her back to him, and, from across the room, he says, “Honey, what’s for dinner?” No response. He takes a step closer. “Honey, what’s for dinner?” Nothing. He takes a step closer and asks again. Same thing. A step closer. Until, finally, she says, “For the fifth time, meatloaf.”

once heard the actor F. Murray Abraham bemoan the fact that, after his Academy Award–winning turn as Salieri in Amadeus, he was, for years, straitjacketed into serious roles and that, in fact, he was very funny.1 (Abraham had played Bottom to great acclaim at Joseph Papp’s Public Theater in New York, after all.) He then told this joke—one of his favorites, he said. It goes like this: A man says to his doctor, “Doctor, I think my wife is going deaf, but I don’t know how bad it is. What should I do?” The doctor says, “Well, when she’s turned away from you, call out her name and if she doesn’t respond move closer until she hears you. Then you’ll know how deaf she is.” So, the man goes home, sees his wife at the kitchen sink with her back to him, and, from across the room, he says, “Honey, what’s for dinner?” No response. He takes a step closer. “Honey, what’s for dinner?” Nothing. He takes a step closer and asks again. Same thing. A step closer. Until, finally, she says, “For the fifth time, meatloaf.”

My wife attests to the sly acuity of this joke, as regards husbands and wives. And I suspect the reason Abraham likes to tell it is that, beyond its fulfilling the basic structural demands of a good joke—a setup followed by a surprising reversal (what the writer Jim Holt calls that “little verbal explosion set off by a sudden switch in meaning” that constitutes a punch line)—it has a pointed design on us and conveys a psychological truth. We laugh, though a little uneasily, reminded that jokes are frequently tinged with the opposite of comedy—something close to tragedy.

The comedian Steve Allen even claimed that “comedy is about tragedy.” Whether or not one takes it that far (and I do mean to push things in that direction), most people would agree that jokes routinely treat all manner of human failings. Certainly, Allen is right to suggest that the “subject matter of most jokes, sketches, funny films, and plays is quite serious.” Comedy and humor have long been subjects for philosophical, rhetorical, and psychological study, attracting top bananas such as Aristotle, Cicero, Immanuel Kant, Sigmund Freud, and so on.

Another Allen—Woody—weighs in on the question of the seriously funny and the raucously serious with this squib, from the opening of Annie Hall:

The . . . the other important joke, for me, is one that’s usually attributed to Groucho Marx; but, I think it appears originally in Freud’s Wit and Its Relation to the Unconscious, and it goes like this—I’m paraphrasing—um, “I would never want to belong to any club that would have someone like me for a member.” That’s the key joke of my adult life, in terms of my relationships with women.

We laugh at Marx’s and Allen’s self-mocking spiel more loudly for its being dipped in the curare of, if not tragedy, then, at least, a discomfiting melancholy. The sentiment of Marx’s line is neatly and wittily expressed, and Allen seizes on it to memorable effect. It would be difficult, in fact, to write a poem that captures the same psychological and emotional truth as winningly and with as much compression, linguistic torque, originality of expression, memorability, and sheer pleasure (though Philip Larkin’s “Annus Mirabilis” comes close).

We laugh at Marx’s and Allen’s self-mocking spiel more loudly for its being dipped in the curare of, if not tragedy, then, at least, a discomfiting melancholy. The sentiment of Marx’s line is neatly and wittily expressed, and Allen seizes on it to memorable effect. It would be difficult, in fact, to write a poem that captures the same psychological and emotional truth as winningly and with as much compression, linguistic torque, originality of expression, memorability, and sheer pleasure (though Philip Larkin’s “Annus Mirabilis” comes close).

Freud rears his furrowed dome in Allen’s monologue for a reason. The chronic analysand Alvy Singer (Allen’s alter ego) name-checks Freud and his book on jokes both to make us smile and to make us ponder—the best jokes get at deeper psychic truths. For Freud “joke-work” and “dream-work” perform similar functions, each with strong ties to the complex machinery of the unconscious. So, then, what of the relationship between “joke-work” and, say, “poem-work,” between Jokes for All Occasions and Palgrave’s Golden Treasury? Aren’t jokes and poems also allied, not least because both are rhetorical acts performed for an audience? (This essay takes its title from the late Michael Donaghey, a brilliant reciter of his own poems, who liked to punctuate his performances with a twist on the comedian’s old line: “These are the jokes, folks.”)

Freud distinguished between “innocent” jokes, which are ends in themselves and serve only to occasion pleasure, and jokes whose content has a pointed design on us. Poems largely fall into this latter category. “But the poem about my great-great-aunt’s creeping schizophrenia is no joke,” I hear some red-faced poet object. But I want to show him that in a sense it is, or nearly, and no less poignant or affecting for all that. I would even go so far as to say poets ignore the essential likenesses between a good poem and a good joke at their peril. The similarities are both technical and rhetorical, as well as psychological—both poems and jokes bear the hoof prints of what the Renaissance poet Fulke Greville referred to as “the Black Ox” of melancholy.

on’t get me wrong: jokes and poems differ—they generally have disparate aesthetic ends. But, in this, poems do not necessarily enjoy the upper hand; they may be, in fact, at something of a deficit. With jokes, for example, their success or failure is clear-cut—either they work or they don’t. Jokes get tested on an audience, which then votes with either laughter or silence (and occasionally derision). Gauging one’s response to a poem or other work of art is more difficult. The bodily symptoms that we experience in response to a poem, if any, “tend to be subtle.” As Jim Holt reminds us, in Stop Me If You’ve Heard This: A History and Philosophy of Jokes:

on’t get me wrong: jokes and poems differ—they generally have disparate aesthetic ends. But, in this, poems do not necessarily enjoy the upper hand; they may be, in fact, at something of a deficit. With jokes, for example, their success or failure is clear-cut—either they work or they don’t. Jokes get tested on an audience, which then votes with either laughter or silence (and occasionally derision). Gauging one’s response to a poem or other work of art is more difficult. The bodily symptoms that we experience in response to a poem, if any, “tend to be subtle.” As Jim Holt reminds us, in Stop Me If You’ve Heard This: A History and Philosophy of Jokes:

A passage in a Bach fugue may fleetingly give you goose flesh. A line from Yeats might make you tingle a bit, or cause the little hairs on the back of your neck to stand up in appreciation. But there is a kind of aesthetic experience whose outward expression is grossly palpable. It involves the contraction of some fifteen facial muscles, along with the simultaneous stimulation of the muscle of inspiration and those of expiration, which gives rise to a series of respiratory spasms accompanied by a burst of vowel-based notes.

Comedians, not poets, as it turns out, best excite “the muscle of inspiration.”

Jokes paint with broad strokes, while poems are more ambiguous and subtle. But perhaps the gap between a gag and a Shakespeare sonnet is not so wide as first imagined. In weighing poems and jokes, I mean to leave aside the obvious similarities between joke-telling and the many varieties of light and comic verse—such as satire, parody, burlesque, ribaldry, epigrams, mock-heroic verse, limericks, clerihews, stuffed-owl McGonagalisms, comic narratives, vers de société, etc.—and consider instead the ways in which so-called “serious” poems share subjects and (most importantly) techniques with common knee-slappers.

Truth, since long before Keats interpreted his Grecian urn, has been—along with beauty—a time-honored purlieu of poetry and art; so, too, with jokes. David Freedman, a joke-writer for the comedian Eddie Cantor, once compiled a list of the six basic types of joke and then, on reflection, added a seventh: “Truth . . . and true portrayal of what happens to you in your life.” As Shakespeare makes plain with the Fool in King Lear, jokes sometimes get at truth more directly and penetratingly than poised, well-reasoned verse, often with uneasy results: “Truth’s a dog must to kennel; he must be whipped out, while Lady the brach may stand by the fire and stink.”

If jokes resemble poems in their ability to apprehend hard-to-handle truths, then in what ways do poems venture onto the territory of jokes? Click on the Wikipedia entry for “joke” (I’m paraphrasing slightly here): Joke-forms are frequently conventional. Jokes use a variety of rhetorical modes, such as stated observations, questions, and brief narratives. Jokes may employ irony, sarcasm, word play, and other devices to achieve their ends. Many conclude with a summary line that cements what has come before it or turns it on its head.

This could all be cross-referenced with the entry on “poetry.” In fact, the entry on jokes includes this passage, lifted from an article by Jessie Lehail, from Darpan magazine: “The rules of humour,” Lehail writes, “are analogous to those of poetry and lend themselves to include timing, precision, synthesis, and rhythm.” To these shared attributes, let’s add Holt’s definition of a punch line quoted above—i.e., “a little verbal explosion set off by a sudden switch in meaning.” Here we have the formula for an English sonnet, in which the reversal is enacted by a terminal couplet. For better or worse, this setup-punch-line structure constitutes the basic movement of the sonnet. (In the Italian sonnet, the reversal comes slightly earlier, in the volta.)

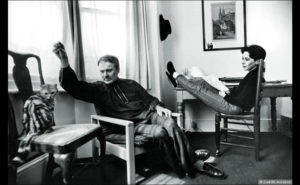

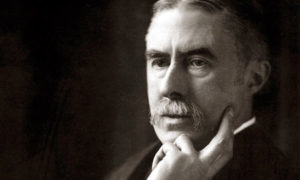

Goeffrey Hill and Alice Goodman, Cambridge, England, 1984; photograph by Judith Aronson, whose portraits of writers and artists have been collected in her book Likenesses: With the Sitters Writing About One Another, published in 2010 by Lintott Press in association with Carcanet Press, UK.

ome poets exploit the sonnet’s self-quarrelling structure (“I grant I never saw a goddess go;/ My mistress, when she walks, treads on the ground:/ And yet, by heaven, I think my love as rare/ As any she belied with false compare”), while others, like Geoffrey Hill, for example, prefer to work against it. (Shakespeare, actually, does both.) Hill is painfully aware of the punch-line effect of a sonnet’s closing couplet, and he doesn’t like it. In his recent, second lecture as Professor of Poetry at Oxford, Hill expressed sympathy for Renaissance poets like Samuel Daniel, Michael Drayton, and Thomas Nashe, who were forced to stare down the conventions of their age and confront the “English sonnet form that threatens to make [one] a laughing stock with its malign final couplet.” Hill cites Shakespeare’s Sonnet 140 as an example of a poem in which the inherent flow of “this particular sonnet form—three quatrains and a couplet—has been overcome by the though-drive of cumulative energy”:

For if I should despair, I should grow mad,

And in my madness might speak ill of thee:

Now this ill-wresting world is grown so bad,

Mad slanderers by mad ears believed be,

That I may not be so, nor thou belied,

Bear thine eyes straight, though thy proud heart go wide.

In order to succeed, Hill argues, “the final couplet must seem the logical—or, as often in poetry, the pseudo-logical—consummation of the preceding twelve lines, not as [inherently, he implies] a pathetic attempt to answer back.” Final couplets that perform a surprising or contradictory turn—in other words, that act like punch lines—have, for Hill, an “overriding tendency to sound merely flippant or silly.”

Hill’s resistance—beautifully managed in a number of the last century’s finest sonnets, including “Funeral Music,” “An Apology for the Revival of Christian Architecture in England,” “Requiem for the Plantagenet Kings,” and others—proves the rule with regard to the couplet’s tendency to “answer back”; he’s at considerable pains to avoid it.

To misconstrue this back-talking rhetorical movement is to misunderstand the sonnet. This is what happens, for example, when poets describe sonnets as elegant “containers,” like so many Louis Vuitton bags for toting around their personal items. I imagine these container sonnets being wheeled through the aisles of Poetry Mart, as the poet grabs armloads of shelf-damaged tropes and hackneyed phrases and adds them to the cart. The notion of poetic forms as containers makes me twitch. I immediately think of an airless and inescapable cell. I hear the sound that Ugolino heard of the door bolting shut and of his starving children crying “Eat us, father.”

Sonnets must not be filled up or filled in or filled out. Better to think of them the way we think of jokes, as a performance, an action, as a cannily modulated flow of connotative and surprising language. The measure of success is not how well the poet fulfills the formal requirements (something easily managed with a little practice) but how well the poem modulates the flow of expressive language through rhythm, timing, originality, and surprise.

ther fixed poetic forms echo joke structures as well. The refrains, for example, in forms such as the ballade, villanelle, and triolet make use of what comedians think of as a “callback”—a joke or a tag line that refers back to a joke earlier in the performance. The joke, like a good refrain, is often presented in a different context the second time around. Callbacks come at the end of a set and aim to create an effect of familiarity and recognition. Most well-turned refrains function this way. Take, as an example, the nonce-form refrain in Billy Collins’s ruefully titled “Hangover”:

ther fixed poetic forms echo joke structures as well. The refrains, for example, in forms such as the ballade, villanelle, and triolet make use of what comedians think of as a “callback”—a joke or a tag line that refers back to a joke earlier in the performance. The joke, like a good refrain, is often presented in a different context the second time around. Callbacks come at the end of a set and aim to create an effect of familiarity and recognition. Most well-turned refrains function this way. Take, as an example, the nonce-form refrain in Billy Collins’s ruefully titled “Hangover”:

If I were crowned emperor this morning,

every child who is playing Marco Polo

in the swimming pool of this motel,

shouting the name Marco Polo back and forthMarco Polo Marco Polowould be required to read a biography

of Marco Polo—a long one with fine print—

as well as a history of China and of Venice,

the birthplace of the venerated explorerMarco Polo Marco Polo

after which each child would be quizzed

by me then executed by drowning

regardless how much they managed

to retain about the glorious life and times ofMarco Polo Marco Polo

I’ve reneged a bit on my promise to avoid comic verse, though not entirely. Collins is a funny poet to be sure, but he’s not a comedian per se. Much of the poignancy of his poems—not to mention his success with audiences—comes from his understanding of how poems and jokes work together to affect as well as tickle the listener. The relentlessness of this single-sentence poem, as it escalates into something like menace, makes us laugh but also brings home the palpable discomfort of the poet’s physical and mental state.

The callback functions equally well in serious poems, such as Anthony Hecht’s dramatic monologue “Death the Whore,” from Flight Among the Tombs, which begins with an initial, bleak image of smoke rising in a desolate landscape:

Some thin gray smoke twists up against a sky

Of German silver in the sullen dusk

From a small chimney among leafless trees.

The paths are empty, the weeds bent and dead;

Winter has taken hold. And what, my dear,

Does this remind you of?

Readers familiar with Hecht’s harrowing poems of the Holocaust and the Second World War will find the image of smoke against a sky of “German silver” particularly haunting. The woman speaker, who has come to a bad end after being cast off by the man she is addressing, returns to this image at the close of the poem with eerie force:

There was no funeral, no cemetery,

Nowhere for you to come in pilgrimage—

Although from time to time you thought of me.

Oh yes, my dear, you thought of me; I know.

But less and less, of course, as time went on.

And then you learned by a chance word of mouth

That I had been cremated, thereby finding

More of oblivion than I’d even hoped for.

And now when I occur to you, the voice

You hear is not the voice of what I was

When young and sexy and perhaps in love,

But the weary voice shaped in your later mind

By a small sediment of fact and rumor,

A faceless voice, a voice without a body.As for the winter scene of which I spoke—

The smoke, my dear, the smoke. I am the smoke.

The seed planted at the opening bears fruit pages later, as the poem, like the stand-up’s act, comes full circle, with a rhymed couplet that is both a heightening and a return.

ffinities between jokes and poems go beyond their structural patterns to their very fabric, like rivalrous siblings recombining the same DNA. Poems and jokes handle words in similar ways and often to similar ends. Both sift experience and convey it to an audience through techniques of wordplay and compression.

ffinities between jokes and poems go beyond their structural patterns to their very fabric, like rivalrous siblings recombining the same DNA. Poems and jokes handle words in similar ways and often to similar ends. Both sift experience and convey it to an audience through techniques of wordplay and compression.

In his characteristically exorbitant foreword to his collection is 5 (1926), E. E. Cummings offers as a theory of poetic technique the “Eternal Question And Immortal Answer of burlesk, viz. Would you hit a woman with a child?—No. I’d hit her with a brick.” This rhetorical pratfall captures what Cummings prized as “that precision which creates movement.” This precise mechanics of expression, admired by Cummings, is the poet’s bread and butter. As the philosopher Henri Bergson suggests in his essay “Laughter” (1900), it’s also the primary business of humor: “the comic is something mechanical encrusted upon the living.” In poetry, we have the mechanism of the poem clicking shut at the end, as Yeats hoped it might. (This is different from the poem as “container,” since the image describes an action—the crispness of the closing—and suggests how well the poem works not how well it contains.)

In his characteristically exorbitant foreword to his collection is 5 (1926), E. E. Cummings offers as a theory of poetic technique the “Eternal Question And Immortal Answer of burlesk, viz. Would you hit a woman with a child?—No. I’d hit her with a brick.” This rhetorical pratfall captures what Cummings prized as “that precision which creates movement.” This precise mechanics of expression, admired by Cummings, is the poet’s bread and butter. As the philosopher Henri Bergson suggests in his essay “Laughter” (1900), it’s also the primary business of humor: “the comic is something mechanical encrusted upon the living.” In poetry, we have the mechanism of the poem clicking shut at the end, as Yeats hoped it might. (This is different from the poem as “container,” since the image describes an action—the crispness of the closing—and suggests how well the poem works not how well it contains.)

In his book How to Be Funny: Discovering the Comic in You, co-written with Jane Wollman, Steve Allen considers the mechanics of joke telling. Almost every verbal element he considers has a corollary in poetry. Here are a handful:

1. The Play on Words: Wordplay is as common in jokes and poetry as pigeons in a park. Wit (both capital W and small w), music, and surprising twists of sense are essential to both vaudeville zingers and heart-sick verses. Wordplay abides in repetition, alliteration, and, notoriously, in puns. As an example of this last, Allen offers:

Q: Do you know how many drunks there are in the United States?

A: The statistics are staggering.

Puns can be silly, but they can also be searing, as in the tiny poem “Their Sex Life,” a two-liner from The Really Short Poems of A. R. Ammons (1990). A romantic couple’s relations are described simply as

One failure on

Top of another

The wit, as the poet David Lehman points out, is in “the lining, the way the first line is ‘on top’ of the second.”

Puns get a bad rap. Stephen Leacock, in Humor and Humanity: An Introduction to the Study of Humor (1938), dismisses them with a scowl: puns act like insidious weeds, “denounced and execrated but refusing to die.” Leacock then denounces them in Latin: Expellas furco, tamen usque recurrit [sic], a bit of Horace that he misspells. In other words, you may drive puns out with a pitchfork, but they keep coming back. Leacock defines a pun as “the use of a word or phrase which has two meanings [that] the context brings into glaring incongruity.” Professor Edward Tayler of Columbia University, on the other hand, has commended the pun for its unique ability to call into meaningful relation different lexical galaxies, as in Herrick’s “Upon Julia’s Breasts”:

Display thy breasts, my Julia—there let me

Behold that circummortal purity,

Between whose glories there my lips I’ll lay,

Ravish’d in that fair via lactea.

Another defender of the pun, the poet Thomas Hood—a noted nineteenth-century practitioner (some would say perpetrator) of puns—wrote, “However critics may take offence/ A double meaning has double sense.” Many of Hood’s own puns, it should be noted, fall short of this lofty standard. Leacock calls Hood the “blackest spot in a darkened sky” of Victorian punning. A couple of examples gives the basic sense: “He went and told the sexton, and the sexton tolled the bell” and “A cannon ball took off his legs, so he laid down his arms.”

Groan. Well, yes, exactly. What makes a bad joke is often what makes a bad poem. The formal convention is dutifully followed without sufficient innovation or surprise; the received form is not enough.

2. The Reverse Formula: Jokes and poems frequently flip expectations, as Henny Youngman does in this saucy tidbit:

2. The Reverse Formula: Jokes and poems frequently flip expectations, as Henny Youngman does in this saucy tidbit:

The place I worked last week is kind of run-down. Between my dressing room and the room where all the circus girls change clothes there’s actually a hole in the wall.But I don’t care; I let ’em look.

Following the well-trodden path from the ridiculous to the sublime, we arrive at Gerard Manley Hopkins’s “Spring and Fall”:

Margaret, are you grieving

Over Goldengrove unleaving?

Leaves, like the things of man, you

With your fresh thoughts care for, can you?

By poem’s end we learn, counter to expectations, that:

It is the blight man was born for,

It is Margaret you mourn for.

The end of the poem is not wholly unanticipated, but there is something about the final, sententious utterance that gives one the sense of a revelation in the moment.

3. The Exaggeration Formula: “One of the best jokes ever written,” Allen claims, “was [and here’s a third Allen!] Fred Allen’s line about a scarecrow that was so scary the crows not only stopped stealing corn, they brought back corn they had stolen two years earlier.” Overstatement produces a powerful rhetorical affect, though, linguistically, it can be a bit unstable. Leacock, in an earlier book, Humor: Its Theory and Technique (1935), rightly identifies the half-life of hyperbole. No sooner is its effect felt than it is absorbed into the language and recirculated beyond its ability to move us: “The very familiarity of words weakens them,” he tells us. “To say that man is ‘incensed’ or ‘melted’ sounds quite literal and ordinary. We have to find a new exaggeration. Thus moves language.”

Poets relish overstatement and are forever pushing things further and further. The whole tradition of commendatory verse, for example, lives by exaggeration, and exorbitance is a commonplace of Petrarchanism. After endless Italianate moonings by poets in the sixteenth century, Shakespeare comes along to clear the air in Sonnet 130 (though he himself could hyperbolize with best of ’em):

My mistress’ eyes are nothing like the sun;

Coral is far more red than her lips’ red;

If snow be white, why then her breasts are dun;

If hairs be wires, black wires grow on her head.

This canny downplaying brings us to the opposite end of the spectrum: understatement, or what Leacock refers to as meiosis. Understatement, he believes, “probably flourishes more among English writers and English people generally than anywhere else in the world. . . . English people abhor sentimentality (the overdone expression of feeling), prefer to keep their sorrows silent rather then to parade them, and admire reserve and reticence.” He gives some amusing examples: “It will be recalled,” he chortles, “how the war news from the North Sea used to call it ‘certain signs of activity’ when two or three war ships clashed together; and when the Germans bombarded the Yorkshire coast, spoke of this as ‘liveliness.’”

For examples of comic British understatement, simply perform Sortes Virgilianae anywhere in the works of P. G. Wodehouse (whose unique gift was for unstated hyperbole). Or consider this eyebrow-raising account, by Jude Sheerin, of cool under pressure:

In 1982, a British Airways flight lost power when it was engulfed by volcanic ash over West Java. The pilot told his passengers: “Ladies and gentlemen, this is your captain speaking. We have a small problem: all four engines have stopped. We are doing our damnedest to get them going again. I trust you are not in too much distress.” The engines were restarted and the plane landed safely.Understatement, it seems, is woven into the British DNA. One can find it way back in the Old English epic poem Beowulf, which contains the line “that [sword] was not useless to the warrior now.”

For other examples of English understatement in martial poetry, A. E. Housman is the great master. Here is the last stanza of number xxxvi from More Poems (1936):

For other examples of English understatement in martial poetry, A. E. Housman is the great master. Here is the last stanza of number xxxvi from More Poems (1936):

Here dead lie we because we did not choose

To live and shame the land from which we sprung.

Life, to be sure, is nothing much to lose;

But young men think it is, and we were young.

4. The Cliché: Freud, in Jokes and Their Relation to the Unconscious, examines the scientist and satirist G. C. Lichtenberg’s use of the analogy “It is almost impossible to carry the torch of truth through a crowd without singeing someone’s beard.” “No doubt that seems to be a joke,” Freud writes,

but on closer examination we notice that the joking effect does not arise from the analogy itself but from a subsidiary characteristic. “The torch of truth” is not a new analogy but one that has been common for a very long time and has become a cliché—as always happens when an analogy is lucky and accepted into linguistic usage. Though we scarcely notice the analogy any longer in the phrase “the torch of truth,” it is suddenly given back its full original force by Lichtenberg, since an addition is now made to the analogy and a consequence is drawn from it.

The same revival of hackneyed expression takes place in Kay Ryan’s “Home to Roost,” which riffs on the old barnyard idiom:

The same revival of hackneyed expression takes place in Kay Ryan’s “Home to Roost,” which riffs on the old barnyard idiom:

The chickens

are circling and

blotting out the

day. The sun is

bright, but the

chickens are in

the way. . . .

Ryan’s slender poem (employing what she has termed “recombinant” rhyme) ends:

. . . These

are the chickens

you let loose

one at a time

and small—

various breeds.

Now they have

come home

to roost—all

the same kind

at the same speed.

The lock-step return of the chickens produces a smile and a shudder at once.

Horace encourages this sort of verbal rehabilitation in his Ars Poetica: “You will express yourself eminently well, if a dexterous combination should give an air of novelty to a well-known word” (translated by C. Smart and E. H. Blakeney). Both poets and comics find it germane to pick up worn-out phrases and hold them up to the light.

5. Bisociation: This aspect of jokes is described by Arthur Koestler in his book The Act of Creation (1964). Koestler’s term refers to “the mixture of concepts from two contexts or categories of objects that are normally considered separate by the literal processes of the mind.” Bisociation, according to Koestler, “means to join unrelated, often conflicting, information in a new way.” (Freud, too, refers to “the coupling of dissimilar things” in jokes.) While Koestler sees such incongruities as leading to laughter, these same incongruities are the essence of poetic Wit, as described by Samuel Johnson: “a kind of ‘discordia concors’; a combination of dissimilar images, or discovery of occult resemblances in things apparently unlike.”

It is difficult to share Johnson’s reservations about Donne, whose conceits were so masterly:

It is difficult to share Johnson’s reservations about Donne, whose conceits were so masterly:

Our two souls therefore, which are one

Though I must go, endure not yet

A breach, but an expansion,

Like gold to aery thinness beat.If they be two, they are two so

As stiff twin compasses are two;

Thy soul, the fix’d foot, makes no show

To move, but doth, if th’ other do.And though it in the centre sit,

Yet, when the other far doth roam,

It leans, and hearkens after it,

And grows erect, as that comes home.Such wilt thou be to me, who must,

Like th’ other foot, obliquely run;

Thy firmness makes my circle just,

And makes me end where I begun.

The Renaissance is a gold mine of examples of how poetry and jokes approach one another. The Metaphysical and Cavalier poets relished punning, word play, and raucous humor, all tinged with their signature melancholy.

eyond structures and techniques, a shared sensibility and psychology inheres between comics and poets—both are obsessed with mortality. The actor Edmund Gwenn is thought to have uttered on his deathbed “dying is easy, comedy is hard” (the adage seems to have undergone, like most good poems and jokes, a process of revision). Dying is not a seemly or delicate matter, but it is a laughing matter. And the comedy (and poetry) I most admire is tinged with this sobering awareness. As Tom Disch, the caustic poet and much-missed master of no-holds-barred hilarity, used to say of light verse, “There has to be blood in the grass.”

eyond structures and techniques, a shared sensibility and psychology inheres between comics and poets—both are obsessed with mortality. The actor Edmund Gwenn is thought to have uttered on his deathbed “dying is easy, comedy is hard” (the adage seems to have undergone, like most good poems and jokes, a process of revision). Dying is not a seemly or delicate matter, but it is a laughing matter. And the comedy (and poetry) I most admire is tinged with this sobering awareness. As Tom Disch, the caustic poet and much-missed master of no-holds-barred hilarity, used to say of light verse, “There has to be blood in the grass.”

In his essay “Sherbet in a Turkish Bath: Serious Humor and Serious Poems,” Andrew Hudgins gives this assessment of humor’s dark side:

Jokes swim in the deep waters of death, sex, fear, violence, hate, and innocence betrayed—the stuff of great literature, to the chagrin of many. Auden reminds us that “through the Janus of a joke/ The candid psychopompus spoke,” the psychopompus being Hermes, the god of, among other things, demons and deep truth.

“It isn’t usually happy people who tell jokes,” Hudgins adds. Neither do poets strike me as a particularly jolly bunch, though they can be uproariously funny, both personally and in print. As mentioned earlier, Fulke Greville believed his poems were not for those upon whose foot the Black Ox (of melancholy) had not already trod. So, too, Baudelaire, Rochester, Larkin, Dickinson, Frost, Hecht, and all the poets quoted in this essay.

The poet William Matthews understood, like any comedian worth his greasepaint, that, often, life amounts to just so many thwarted expectations. A harsh lingua franca of disappointment constituted for him “our burled, unspoken, common language.” In his poem “Dire Cure,” Matthews anxiously (jokingly!) rehearses names for his wife’s life-threatening tumor:

. . . I couldn’t stop

personifying it. Devious, dour,

it had a clouded heart, like Iago’s.

It loved disguise. It was a garrison

in a captured city, a bad horror film

(The Blob), a stowaway, an inside job.

If I could make it be like something else,

I wouldn’t have to think of it as what,

in fact, it was: part of my lovely wife.

Early in his essay “Laughter,” Bergson observes that laughter and emotion are incompatible: “It seems as though the comic could not produce its disturbing effect unless it fell, so to say, on the surface of a soul that is thoroughly calm and unruffled. Indifference is its natural environment, for laughter has no greater foe than emotion.” Others have argued that humor and joke-telling work as an avoidance of emotion, a buffering effect, but humor can also be fraught with emotion: like poetry, it accesses our most difficult feelings, even as it orders them and elucidates them.

Even in light verse, it is possible to discern beneath the poem’s comic veneer a motivation seated in deep feeling. This, as Freud suggests, is the point at which a surface jest becomes a full-on joke (or, in our case, a poem). Such deepening occurs in Robert Conquest’s wry and devastating “Progress,” perhaps the most brilliant limerick of the twentieth-century:

There was a great Marxist named Lenin

Who did two or three million men in.

That’s a lot to have done in,

But where he did one in,

That grand Marxist Stalin did ten in.

The music is sprightly but the matter is powerful and even tragic.

The great poet and critic Paul Valéry believed that at the root of the human condition was a shadowy center: “Latent in every man” he believed, “is a venom of amazing bitterness, a black resentment; something that curses and loathes life, a feeling of being trapped, of having trusted and been fooled, of being the helpless prey of impotent rage, the victim of a savage, ruthless power.” It is out of such stuff that jokes and poems are made.

For his part, Gershon Legman, a renowned dirty-joke collector—who, among his many accomplishments, introduced origami to the West, bedded Anaïs Nin, and invented the vibrating dildo—noted the “infinite aggressions” of jokes and their tellers. This sentiment was echoed by the theater critic John Lahr, son of the comedian and actor Bert Lahr. In speaking about the comedy of his father’s generation, namely burlesque and vaudeville, he noted the homicidal nature of the language used by comedians: I killed, I murdered ’em, I knocked ’em dead, I died out there.

Death is an enduring subject for comedy and poetry because it is, as Ted Cohen puts it in Jokes: Philosophical Thoughts on Joking Matters, permanent and universal: “Everyone is aware of it; everyone will know what you are talking about the moment you mention death. In this regard, death is like sex, . . . and marriage and illness and love and youth and old age—all things that we may presume many of us know about.” Anthologies of both humor and poetry are filled with the stuff.

![]() y considering what poems share with jokes, poets may better understand a number of crucial aspects of their work. To wit: poems are performed for an audience. As Gideon O. Burton of Brigham Young University writes on his website “Silva Rhetoricae”: “All rhetorically oriented discourse is composed in light of those who will hear or read that discourse.” It is crucial for a poet to have an audience in mind, even if it is only an imagined ideal reader. A poem, like a joke, is carefully crafted speech that is then tested on an auditor, not merely the skillful fulfilment of a form. Poems are best understood not as empty containers but as rhetorical strategies; they either convince or they don’t. Like jokes, poems are shaped by timing, repetition, and surprise. Wielding these elements with precision creates movement, and the force of that movement is conveyed to the seasoned reader, by repeated encounters with the poem. Each time through, the effect of the poem should be palpable.

y considering what poems share with jokes, poets may better understand a number of crucial aspects of their work. To wit: poems are performed for an audience. As Gideon O. Burton of Brigham Young University writes on his website “Silva Rhetoricae”: “All rhetorically oriented discourse is composed in light of those who will hear or read that discourse.” It is crucial for a poet to have an audience in mind, even if it is only an imagined ideal reader. A poem, like a joke, is carefully crafted speech that is then tested on an auditor, not merely the skillful fulfilment of a form. Poems are best understood not as empty containers but as rhetorical strategies; they either convince or they don’t. Like jokes, poems are shaped by timing, repetition, and surprise. Wielding these elements with precision creates movement, and the force of that movement is conveyed to the seasoned reader, by repeated encounters with the poem. Each time through, the effect of the poem should be palpable.

1 This essay was originally given as a talk in the poetry symposium of “Writing the Rockies,” a conference sponsored by Western State College of Colorado in July 2011. It originally appeared in print in the 30th Anniversary September 2011 issue of The New Criterion.