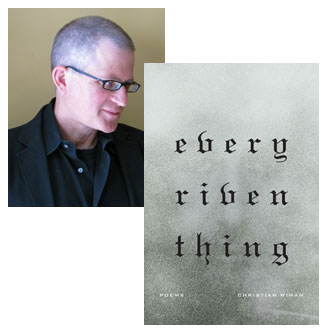

Reviewed: every riven thing by Christian Wiman. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010. 93 pages.

Reviewed: every riven thing by Christian Wiman. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2010. 93 pages.

From its hardcover heft and granite-engraved dust jacket (remove the jacket and a black, bible-like, hardback cover is revealed), to its ivory paper stock and black section divider pages (complete with roman numerals blazoned in white), every riven thing announces the solemnity it aims to deliver and does: verses crafted as if with a chisel on stone, the weight of each line falling into the congregation of a hushed readership, organ sounding in the background—

There is no consolation in the thought of God,

he said, slamming another nail

in another house another havoc had half-taken.

grace is not consciousness, nor is it beyond.

(“Hammer is the Prayer”)

Wiman’s preaching style doesn’t truly take hold until the second section of the book, after the first section’s poems set the scene for a sensitive boy-child’s coming to reckoning with mortality. Though it takes awhile to get going, the lofty rhetoric rolls from Wiman’s tongue with alarming frequency and to no other purpose but to ruminate and moralize:

There is a lake from which no sun returns.

Brown, glintless, it lies in the land like the land.

A man might be forgiven for thinking he

might walk that water like any acre’s dirt,

might stride the man-made dam like a god in mind.

*

If it is grief that brings him here, it is

a grief in which the land participates,

a dry grief, a grief of heat, in which the trees’

contortions tighten and the cacti crouch.

He stares and stares at the unchanging lake.

(“The Reservoir”)

No question but that this poet knows his business. Such verses show awareness of meter, rhyme (internal and end), a talent for rhetorical use of repetition (“a grief in which the land participates,/a dry grief, a grief of heat, in which the trees’/”), apt metaphorical phrasing (“trees’/contortions tighten and the cacti crouch”), as well as a graceful use of syntax, especially of the compound-complex kind. But hark! The ghost of Shelley’s “Ozymandias” haunts with its “lone and level sands [that] stretch far away” and Hopkins hovers near that cacti “pitched past pitch of grief.” The nineteenth-century turn that Wiman favors is one that begins to require some indulgence on the part of the reader:

If I say I loved the seagull

tethered to its cry, the cypress’s imprisoned winds,

speak to the brink of my hands

a moss-covered rock

soft and knobby as a kitten’s skull.

If I say I loved.

(“Late Fragment”)

Edna? Is that you? But the nineteenth century may be preferable to the seventeenth, which is where the poems tend to congregate when they want to confront God or to impart wisdom (usually a little bit of both):

God let me give you now this mind of dying

fevering me back

into consciousness of all I lack

and of that consciousness becoming proud:

There are keener griefs than God.

They come quietly, and in plain daylight,

leaving us with nothing, and the means to feel it.

(“The Mind of Dying”)

I struck the board, and cried “No more!” then fled Him, down the nights and down the days, shouting “Batter my heart, three-person’d God!” With stakes this high (life or death), it’s hard to believe in the reality of danger when the poems themselves fall back on the poetic strategies of another time. Where is the precipice? The fear? The heat that drives them on? Writing like Hopkins is a laudable accomplishment, a job jolly well done, but eliciting something original, as Hopkins did for his time, is what’s missing in Wiman’s work. One only needs to compare Wiman’s attempt to record spiritual struggles in these poems with those of his contemporaries, D.A. Powell and Franz Wright–both of whom have managed to write searing and wholly original poems dealing with God, mortality and spiritual suffering without invoking clichés of diction, form, or sentiments from centuries past.

If one believes in the biography as a necessary accoutrement to the work, then Wiman’s is unimpeachable (he has been diagnosed with an incurable cancer), but high-minded and concerned with important matters as these poems are, and as grounded in real biography as they purport to be, they fail to impart a sense of what’s at stake. They only talk about what’s at stake:

But the world is more often refuge

than evidence, comfort and covert

for the flinching will, rather than the sharp

particulate instance through which God’s being burns

into ours. I say God and mean more

than the bright abyss that opens in that word.

(“2. 2047 Grace Street”)

There’s no real sense of urgency, only an urgency once-removed, something talked about. If the “I” in this collection were a persona (and perhaps it is), I would object to its lack of persuasiveness. I am not convinced that a voice so careful, earnest, and proper (or a poet/persona so invested in crafting each line in the shape and echo of Hopkins, Herbert, Donne or others of their bygone ilk) is one that can take contemporary readers by the collar and shake them, or shock them, into an awareness that the poet claims to have attained with great difficulty. Suffering, hard work, and integrity do not, unfortunately, make an original, exciting, or memorable poem.

As for the collection as a whole, there are several poems here that strike me as exercises. (To put it more generously, they are intended to show Wiman’s range, that he can toss off a few on the side while forging the tough ones in the secret smithy behind the altar.) This is an unfortunate editorial decision, as the book would have benefited from a culling of at least 10 poems. Its ponderous tone is not alleviated, but instead trivialized, by the inclusion of such ditties as “The Wind is One Force,” wherein Wiman lightens things up by applying end rhymes to the same lot of grave observations and admonitions. Here, the reader is allowed to get up and stretch, greet his pew mates, and relax a bit. It’s all a rueful chuckle after all, this thing we call life:

…

it all goes soft as snores,

murmurs, some vague ache,

as if dreams were a course

a storm might take,

a people’s hearts its source,

their bones its wake.

…..

Wiman’s every riven thing is, perhaps, a book one should read—important poems written by an important poet who also happens to be editor of the country’s most important poetry journal, and who is published by one of the country’s most important publishers, and lauded in all the right, important places–but the prospect of becoming a better person by spending any more time with these poems, is, finally, unimportant. I would rather spend time reading a collection that surprises me again with the power of poetry. This is not that book.

I have big objections to this review. The primary bases of Houlihan’s critique are the assumptions that (1) novelty is the source of poetry’s power and that (2) novelty is the same as originality. She writes, “With stakes this high (life or death), it’s hard to believe in the reality of danger when the poems themselves fall back on the poetic strategies of another time. Where is the precipice? The fear? The heat that drives them on? Writing like Hopkins is a laudable accomplishment, a job jolly well done, but eliciting something original, as Hopkins did for his time, is what’s missing in Wiman’s work.” First, why should we agree with her assumption that in order for a poem to be convincingly urgent it has to somehow invent novel “poetic strategies” (as opposed to those “of another time”)? (And why does Houlihan assume that it’s a weakness to use poetic strategies gleaned from the great poets of the past? Why is that “fall[ing] back,” a phrase used pejoratively by Houlihan?) Second, if the standard Houlihan holds for poetic value is something as “original” as Hopkins’ work, then I’m afraid we may not have a single living poet who would qualify as acceptable.

Every Riven Thing is one of the best books written in the last ten years. Time will tell. Joan Houlihan doesn’t like the subject matter of religion which she calls “preaching” or “moralizing”. Just because the language is rife with internal and end rhyme doesn’t mean it’s 19th century.

Craft + subject matter does not equal power or poetry that matters. I think that’s what JH is looking for, and so am I. I echo her conclusion: this is not it.

It’s okay as a throwback to older poetry, but it’s not compelling to read. Even contemporary painters–– someone like Condo, who is influenced by classical paintings in his work, injects something strange and new. And we have only to look at paintings––– in a book of poetry 90 pages long–– we must read through it.

@EDW: What it sounds like Houlihan is looking for is poetry that is ever novel in its strategies (stylistics, form, voice) (nevermind the fact that this would be impossible in any art form and nevermind the fact that all of our greatest poetry relies on its gleanings from the literary tradition). She locates “the precipice,” “fear,” and “the heat that drives them on” theoretically in superficial features of poems’ forms (“poetic strategies,” in her phrase). That’s her primary mistake, as following that idea to its logical conclusion would necessitate claiming that a poem that met certain superficial criteria would be “urgent” and “original” and ultimately “important,” even if the poem were, in actual experience, uninteresting or hogwash. She also seems to be making the strange claim that sincerity and urgency can only find expression to the extent that they throw off tradition and the past (“it’s hard to believe in the reality of danger when the poems themselves fall back on the poetic strategies of another time. Where is the precipice? The fear? The heat that drives them on?”). Well, I say, WHAT IN THE WORLD DOES THE ERA OF A POEM’S INFLUENCES HAVE TO DO WITH THE POEM’S “REALITY OF DANGER” OR “HEAT,” OR THE POET’S OR READER’S FELT “PRECIPICE” OR “FEAR”? Houlihan’s implied claims are assumptions that do not seem to be at all based on logic.

Luke Haskins asks : “First, why should we agree with her assumption that in order for a poem to be convincingly urgent it has to somehow invent novel “poetic strategies” (as opposed to those “of another time”)?”

Where Joan writes “poetic strategies” I might put “contemporary idiom” or such like – but I agree with the substance of her statement. A contemporary poet’s relation to great forebears & models is very tricky & full of pitfalls. We have to do two things at once : absorb the past and not be overshadowed by it. When a poet leans too heavily on the high old rhetoric, the outcome is just that : rhetoric, rather than something really new. Originality remains a sine qua non.

@Luke: I wish I had had an “intense emotional reaction” to Wiman’s poems, they certainly deserve one. Unfortunately, the poems struck me as technically accomplished but dull. There are several reasons why this might be so, and I cited some of them, including a reliance on familiar, sometimes archaic, poetic strategies. Obviously, originality (I don’t use the term novelty, you do) is primary to a poem’s success. Of course, originality is, as Henry says, the sine qua none, and may simply (simply!) reside in voice. There are no “superficial criteria” or even non-superficial criteria that a critic or reader can list and a poet can then apply and voila! a poem is great. In the case of poetry, as in all art, the whole is much more than the discrete parts.

@John: Obviously, the subject matter is not a problem for me (I cite two of Wiman’s contemporaries who deal with religious material in more exciting ways) and poets can get preachy without needing to go near religious material. It’s tone, not subject matter. I favor sound in poems and I don’t think rhyme by itself is 19th century. That century is signalled by a constellation of things including archaic (“poetic”) diction, inversion, as well as end rhyme. Nowadays, end rhyme seems to show up mainly in light verse.

@Ellen: Yes, the poetry needs to matter. To the reader as much as to the writer.

@Kathy: yes, it’s a long book and it makes unreasonable demands on a reader’s time and attention. Some poems are weaker than others. It needed a better editor.

@Henry: thanks for reading what I wrote.

@Joan: Thank you for joining the conversation. I appreciate your explanation in the comment more than what seems to me a review containing overly pejorative and mocking language. (Speaking of tone…) So, re: your comment to Henry, he is not the only one who read what you wrote. Perhaps his interpretation of what you wrote was closer to your intended meaning, but my interpretation was also justified based on the words and the tone. I purposely introduced the term “novelty” to describe what it sounded to me like you were after. But, as I said, I appreciate your clarifications in your comment, though I am quite surprised to hear your idea that end rhyme shows up mostly in light verse today, which I’m guessing must be based more on what you personally choose to read than on objective observation (exceptions, off the top of my head and in no particular order: Seamus Heaney, Richard Wilbur, A. E. Stallings, Paul Muldoon, Ernest Hilbert, Ashley Anna McHugh, Melissa Range, Natasha Trethewey, Morri Creech, Erica Dawson, Adam Kirsch, Geoffrey Hill, Fred Chappell, Gjertrude Schnackenberg, Sherman Alexie…and it could go on and on).

Ultimately, I’m much less concerned with your conclusions about Wiman’s poems than I am about the stated reasons for your dislike, some of which sound to me like a distaste for the past and a call for novelty as the means of originality (though I know you don’t use the former term — the word is my interpretation of the language of the review).

Just A Trace

Poems lack love and much lustre,

And lack flavor like sweet custard,

Trying to fill your very being,

Which is worth tasting and seeing.

How grand is great grandiloquence,

Or fool seeing which side of fence,

That he just may happen to be on;

Then life which was now has gone

So see the spirit inside of me;

Release my soul so it can be free,

And of God, give me His grace,

Eve if small or just a trace.

Odd. I’ve never been at all a fan of Wiman’s, and am often accused of thinking innovation everything in poetry. I’m not big on the apparent subject matter of this collection, either. But I found the quoted passages at least as good as the work of any other poet reviewed in CPR, and some of that is excellent if not the best around. His diction and imagery seem generally fresh to me, and I like the resonance with earlier poets–including, most pronouncedly for me, Stevens, one of my three favorite pre-1960 American poets.

I’d be very interested to hear what you had to say about the poetry of the late M. A. Griffiths.

http://ramblingrose.com/grasshopper/

She was a fearless poet who didn’t give a damn about po-biz, and her poetry is a damn sight better than Wiman’s. Why don’t you review her book?

Better Wiman is remembered for this tombstone of a book rather than the wreckage he left of poetry magazine.

I would like to see more poems of a serious nature, and more poems about death. Thomas Hardy thrills me. I had a near death experience. It was so horribly wonderful. Wiman may be facing the grave a little earlier than some of us. Yet the grave yawns before us all, a rotten mouth full of broken teeth.

Without addressing the substance of this review, it does seem problematic to me that it is written by a poet whose most recent book was given a hugely unfavorable review in the journal edited by Christian Wiman. Whatever you might want to say about her claims and criticisms, Jean Houlihan can hardly be regarded as impartial on this subject. The supposed objectivity of her critique is completely negated by her personal investment in rejecting Wiman’s poetry and poetic standards. Would she have written the same review if her book had been praised in Wiman’s journal? Probably not. The mystery is not why this review was written, but why it was published. Who wouldn’t want to slam the work of an editor who has publicly dismissed their work, in “the country’s most important poetry journal”? I know that under the same impetus I’d like to say a few nasty things about Wiman and his journal, and I have no doubt that there are no shortage of writers who would like to say the same things about me and my journal–but professionalism, a sense of how journals work, and the vital necessity of editorial subjectivity (Wiman was put in charge of Poetry not because he’s “impartial,” but because he stands for something the board of the journal consider important) make such statements self-evidently childish. This journal needs to give some serious thought to the necessity of at least gesturing towards impartiality in the assigning of reviews.

Mr. Feld, in the matter of a possible tit-for-tat review of Wiman’s book, I take your point even though Wiman is one (or more) “tats” removed since he himself did not review my book, only published, in your words, a “hugely unfavorable” review of my book. It could be argued that perhaps I shouldn’t have chosen to review his book because of the mere appearance of partiality (even though, a book review, being one person’s opinion, is anything but impartial). Yet consider: who, out of the thousands of poets who are desperate for publication in Poetry, would dare to review his book (that is, to review it honestly, if not impartially)? In that sense, who better to review it than someone who has had it both ways with Poetry: hugely favorable and hugely unfavorable? A review that is completely impartial is one that is also completely useless. I think you are objecting not to partiality but to the kind of partiality. It may not be a hugely favorable review; however, I have tried to be thoughtful and think it is well-considered.

Meanwhile, your complaint against CPR, that we should at least “gesture toward impartiality” is what you here extol in Poetry—a lack of impartiality in editorial decision-making! So, which is it? Impartiality or “the vital necessity of editorial subjectivity?” I happen to agree with the idea of a vital editorial subjectivity, and that a journal should have a discernible viewpoint—it should “stand for something.” But who can discern the editorial viewpoint of Poetry? It seems to be, to put it kindly, eclectic. To put it less kindly, a grab bag. Meanwhile, it is CPR that has a discernible editorial stance, one that values intelligence, integrity, outspokenness, and a dislike of favor-trading—and that’s exactly why I edit and write for it.

At the risk of everything, I need to jump in here. I do not know any of these people personally. I do have my own history of being in and being reviewed by Poetry that includes both very positive and very negative experiences. I also know a lot of thing one knows from listening and reading on line and in real life.

So that is my context. From there, I’d like to say that I think Joan Houlihan’s review is and was brilliant, brave, and on the money. I’m grateful she wrote it and wish I’d seen it sooner. I just saw it now because Mr. Feld’s remarks made it the subject of some talk on face book.

I happen to think, given what I have experienced, read, heard, and known, but mostly, MOSTLY just from the surface argument and writings right here available to everyone, that Mr. Feld is in the wrong, though he may be a nice guy defending something out of all good reasons.

Thanks for your wisdom, courage, and knowledge, Joan Houlihan. Let’s us talk sometime.

Jennifer

For what it’s worth, I agree with JH here. This is a depressing book, even more depressing when the patient/poet (a central fact of this book, no?) makes half-hearted gestures toward acceptance and joy. And yes, I feel he’s constantly moralizing, beating us over the head with his oh-so-precious faith. Well crafted? sure. But also self-aware I would say (all those cute references to the “craft” and “art” of writing), and those similes do pile up.

Is this Christian poetry? Everything says that it is, but yet it is not. The poet is obviously deeply conflicted, or at least determinedly evasive, regarding religious concepts, beliefs, and ideas. It’s Wiman poetry – safe, narcissistic, new agey religion for the Poetry (magazine) geriatric fan-base.

So, go JH! Thank you for your honest review.

There are always going to be readers who don’t like certain poems because the poems are derivative and others who love the same poems because they are linked strongly with tradition. I’m of the latter group here. To say that these poems are just like Hopkins or mere imitations of Donne or Herbert is ridiculous because there are so many techniques and aspects of the poems that are nothing like those three poets. Some people love the iamb, some fear it, some despise it. Some accept it as a crucial part of the English poetry, which it is.

I’m not sure Andrew has a leg to stand on here, though, even though I think Houlihan’s review is wrong and she must not have an ear to hear. I reviewed (positively) Wiman’s book elsewhere though one of my books got butchered by another inept reviewer in Poetry’s pages. I’ve also had poems published in Poetry. So how do I come to my conclusions about his poems? Well, I try to read them and ask myself if it is good poetry based upon all the good poetry and bad poetry I have read. One tries to be objective. I may have had an ax to grind with Wiman over letting such a stupid review of my book (D.A. Powell got it much worse than me in the same review) go to print. But then maybe I want to get more poems in Poetry? I am not concerned whether Poetry Magazine ever takes a poem of mine again. It is a feather in the cap, for sure, but what is a feather in a cap? Who can tell what transpires psychologically with any given critic? I don’t think Houlihan is malicious. Only deaf and probably at odds with a poet whose vigorous religious views don’t match hers.

To call Christian Wiman’s Poetry new-agey is to be a shallow thinker when it comes to religion and philosophy. To read “Dust Devil” or many of the other poems and say that is to be uninformed. How these poems are “safe” I know not. “deeply conflicted”, yes. So which is it? Is it preachy or new agey? It’s neither, and that is why I love the book. It is what Blackmur called for when he wrote: “The art of poetry is amply distinguished from the manufacture of verse by the animating presence in the poetry of a fresh idiom; language so twisted and posed in a form that it not only expresses the matter in hand but adds to the stock of available reality.”

Let’s not confuse Wiman’s own book with what transpires in the pages of Poetry. An editor’s selections does not constitute his creation, and one must distinguish the two, though one may compare them. I dislike most of what Poetry has published in the past three years. But I dearly love Every Riven Thing. It’s a great step forward from his two previous books.

Dear Editors and commentors:

I agree with Houlihan’s verdict, but not with the assumptions on which she predicates her judgments. Wiman’s poems lack the energy of direct experience (however lived the experiences of “real life” which they take for their subject) and seem anxious, in a Charles Wright sort of way, to impart “deep wisdom,” though that wisdom is not proved upon the reader’s pulse with any consistency or force That is what leaves me cold, not the echoes of Hopkins or Donne or whomever. Reviewers with a bone to pick or an ax to grind regarding form and tradition frequently betray their ignorance in literary matters which require some modest degree of historical perspective.

To say that these poems rely on tradition is to say nothing whatsoever about them: so Wiman sounds like Shelley here, Donne there, Herbert elsewhere–doesn’t the synthesis of these styles through the particular manner and contemporary idiom of Wiman constitute an interesting stylistic innovation itself? I think it does, however much I may be left unmoved by the poems themselves. It is, after all, possible to approve of a writer’s technique but not be impressed with his or her vision.

Vision cannot be equated with mere subject matter, moreover. To dismiss religious poetry for being . . . well, religious . . . is to show a profound lack of understanding of humanity. People do, after all, continue to believe in such things, however much that may dismay enlightened critics; should religious people be offended by Stevens’ “Sunday Morning,” then, or Larkins’ “Church Going,” because of their irreligious sentiments? We may all be wrong regarding Wiman, of course: consider Dr. Johnson’s dismissal of “Lycidas,” arguably the greatest pastoral in the English canon, on the grounds of its fussy construction and its lack of genuine emotion.

To return to Houlihan’s appraisal or Mr. Wiman: to imply that Herbert and Shelley are similar because they both use iambs and end rhyme is to betray a frustrating, even laughable ignorance of the tradition, of history, and of all of these astonishingly different writers–like saying Thomas Carlyle is too evocative of Sir Thomas Browne because they both use paragraphs.

I should also point out that there is nothing “searing” about Franz Wright’s artless verse. I delight in well-crafted free verse as well as in strong formal verse, and see no reason to prefer one technique over another; to do so seems, in the twenty first century for God’s sake, incredibly parochial. But Franz Wright’s bathos is unshaped by memorable phrasing, emotional restraint, or technical control of any kind, regardless of the tradition one wishes to lump him in; and there is no freedom from tradition (at this point, even John Ashbery is a canonical figure), only successful or unsuccessful attempts to address it.

Nothing could be more cliche than to continue the tired, hackneyed mode of modernism and postmodernism–as though some smarmy schoolmaster has forbidden us to look backward further than 1917, for fear of catching the “form” virus. Again, silly and parochial from any educated point of view. Just as the modernists looked backward in order to move forward–Eliot and Pound may have broken the back of the pentameter line a hundred years ago, but they also employed it famously in their work, and both used rhyme frequently; they also revered the formal works of the sixteenth and seventeenth century. Perhaps it’s time for us to do so as well. I suspect we may find more in the nineteenth century that is of use to us now–after all, it was in the century of Blake’s “London” when the consequences of industrialism, imperialism, revolution, and “modern” isolation (including isolation from God and the rapidly receding sense of a meaningful tradition) become disturbingly apparent–far more than any of the works of the twentieth, which have been mined, imitated, innovated upon, and reacted against to the point of absurdity.

Perhaps we would do well to look at our twentieth century forebears, a century after the triumph of vers libre over “formal” verse, and follow their historical example rather than merely their aesthetic. Pound and Eliot both took what was useful from the nineteenth century and then reached back further, particularly to the seventeenth century, in order to break free of Victorian cliches. Wordsworth and Coleridge, a century earlier, had broken with the Augustan poets not simply by changing their formal approach, but also by innovating on the content of their verse. Think, too, of the resurrection of the sonnet form, after its eighteenth century moratorium, as a vehicle for meaningful expression.

What modernist cliches have we clung to? On what hackneyed, outdated, untested assumptions do we continue to base many of our aesthetic judgments, despite the fact that Eliot and Pound, Wordsworth and Coleridge alike would dismiss these as irrelevant and desiccated, searching instead for ways to “make it new?” The unfortunate effect of institutionalizing poetry by A.W.P. standards is that it has frozen American poetry in an aesthetic that does not connect to earlier centuries than the twentieth. To look back further than Eliot is considered verboten, as it would imply that young poets have more to learn from Shelley (and from English, not “creative writing,” classes–scholar poets again! egad!) than their M.F.A. mentors, who have themselves worked too hard to acquire the acceptable period style to see their own students jettison it in favor of “old fashioned verse.”

What will happen though, I wonder, when students wishing to reconnect to an older tradition and be taught the nuances of formal poetry find the likes of Houlihan teaching them–postmods with only the crudest historical perspective, the most reflexively conservative aesthetic, and the dullest understanding of what distinguishes one poet from another (simply because they happen to employ some of the same techniques)?

If we must dismiss a poet like Wiman–as perhaps we must–it should not be because he chooses to be influenced by unfashionable models or because radically conservative reviewers disapprove of his methods. Poetry in the new century must–it MUST–find a way to innovate away from the prevailing aesthetic of the last century. There is no other way for it to remain relevant. Some poets–to critics’, teachers’, and reviewers’ dismay–will perhaps be shocked by the audacity of certain poets to reflect a broader, more liberal view of artistic progress–one that understands, as the revolutionary modernists did, how integral backward historical reflection is to forward progress.

Right now at least, the most radical thing a poet could do is to write of contemporary life in received, not invented, forms. To stick with unquestioning fidelity to the current norm is to be a postmodern lemming. Do I advocate form over free verse? Absolutely not. Just don’t bore me with the status quo; I think, after all, that we would all be astonished at just how bored most readers are of contemporary poets. And perhaps, despite our wishes to the contrary, the fault lies with poets themselves, who have proven themselves stubborn in their fetishism of modern assumptions about craft, even to the point of their own irrelevancy.

I must follow up with a question for the reviewer: why does Hopkins, or the seventeenth century, seem so objectionable to her, and how does she propose Mr. Wiman create something new in his own time without echoing the past? Does she prefer the syllabics of Marianne Moore, which are decidedly not in fashion now, but will certainly seem outdated once fifteen or twenty new poets try their hand at the “Pangolin” stanza? Or the heteroglossia of Ashbery, imitated with lock-step fidelity by dozens of poets? Or maybe the stair-step long line of Charles Wright, which he himself brazenly borrowed from Pound? Or would she prefer the tradition of Jorie Graham, an anemic echo of Eliot in our time that has herself spawned dozens of imitators? Or does she prefer the William Carlos Williams long-short-long line variable verse tercet, exploited by Linda Gregerson in several of her collections? What about the sixteen character modest-length free verse line that gets used so reflexively by . . . well, just about everybody? Tradition is a problematic thing for critics like Ms. Houlihan precisely because it doesn’t hold still, as she seems to believe. Precious little is left to be done that hasn’t been done before, and unfortunately, the bold pioneers of a previous age–even free versers like Williams, Stevens, Olson, et al.–become the hackneyed cliches of the next. To exclude free verse from a discussion of “making it new,” and to assume, as Ms. Houlihan does, that somehow freedom from rhyme and meter equals freedom from the past, is to make a catastrophic historical and aesthetic mistake in judgment; it is to betray a naivete for which intelligent readers must, at last, express extreme exasperation. The same thing could said, too, for prose poetry, which is well over a century old, though Mark Strand is publishing some terrific ones as I write this, and the form remains in fashion, relatively speaking. Perhaps critics like our reviewer wish to paraphrase Ed Meese of the Reagan era, claiming that they cannot tell us what novelty is but that they “know it when they see it.” At the end of the day, no matter what tools we dismiss as old hat and outdated, we all must remember that language is the most outdated tradition of them all: we didn’t invent the language, but are merely inheritors of it, and though we may change or add to the meanings of existing words, add a few new things to the lexicon, and revise a few things out as archaisms, it is neither useful or advantageous to throw it all out of the window and insist, with each new generation, that we invent the whole thing anew. Surely there are a few things from the past which might serve us well; and it is a poet’s duty, after all, to keep tradition alive even as she innovates upon it–much like musicians who strive to create a unique sound by borrowing melodies, lyrics, and progression from the past in order to find their voice. If Mr. Wiman seems seventeenth century, perhaps we should thank him for reminding us that those ideas still have sufficient force to be echoed meaningfully by the present. Unfortunately, though, the critical assertion that metered poetry, and formal techniques in general, are no longer expressive is itself a profoundly shopworn cliche. Criticize formal poets all you want, on an individual basis–most of them are bad, anyway, and not just the formal poets of our age–but at least have the intelligence to assess whether it is being used effectively or not, instead of merely dismissing it altogether. To do otherwise is simply lazy.

Please retract my comment from August 30; sometimes I work myself up into high dudgeon, online, and forget humans are reading this stuff.

Wow, I’m loving the strong responses to Joan Houlihan’s review and to the question of Wiman. I’m one of those who are unmoved by the poetry, which seems too self-consciouus to me – but I can’t add to what others have said.

What I will do is shamelessly put in a plug for a sheaf of poems which I’m selling on Amazon, and which you can preview on my website – New Possum, I think these poems may satisfy your longing for something that’s both new and old, and in a more natural form than Wiman’s grab bag (as it seems to me).

In the end, it comes down to which poets you support with your dollar. As a young poet, it’s dreadful to me, the thought that there’s so much stuff out there that no one is going to get any nourishing piece of the pie – I’m talking about dough of course. I’ve done my part, by abandoning the creative writing industry as soon as I was through with school. But if you’re not in it, you’re quite lost. Anyway, check out the book for free, and vote with your wallet, if I’m your candidate.

Thanks in advance, CPRW – how I love you, with my wallet! – for your patience with this bit of self-promotion!

Pingback: Christian Wiman’s –Every Riven Thing– Rant & Review « Damselfly South