As Reviewed By: Ernest Hilbert

Part 9: Anne Sexton

It is a peculiar pleasure to hear Anne Sexton read her poems, though her parched agony carries through and occasionally sends a shiver down the spine. Her voice, smoky and a bit bored even in the earlier recordings, conveys the world-weary, scarred persona that gained her such an enormous and devoted following. Despite the excruciating private torments that formed the basis of her poetry-the girlhood abuses, multiple suicide attempts, the vodka and Thorazine-she was a very public figure. By 1970 she had accumulated innumerable awards and honorary degrees. She formed a touring rock band, Her Kind (after the title of one of her best-known poems), and, in a slim red satin dress, thrilled worshipful audiences with recitations of her incendiary poems, a rock star of poetry. While many of her poems are gaudy and overworked, as one would expect from such a passionate outpouring of painful emotion, her best work shows a poise and strength that places it among the best written in America since the Second World War.

It is a peculiar pleasure to hear Anne Sexton read her poems, though her parched agony carries through and occasionally sends a shiver down the spine. Her voice, smoky and a bit bored even in the earlier recordings, conveys the world-weary, scarred persona that gained her such an enormous and devoted following. Despite the excruciating private torments that formed the basis of her poetry-the girlhood abuses, multiple suicide attempts, the vodka and Thorazine-she was a very public figure. By 1970 she had accumulated innumerable awards and honorary degrees. She formed a touring rock band, Her Kind (after the title of one of her best-known poems), and, in a slim red satin dress, thrilled worshipful audiences with recitations of her incendiary poems, a rock star of poetry. While many of her poems are gaudy and overworked, as one would expect from such a passionate outpouring of painful emotion, her best work shows a poise and strength that places it among the best written in America since the Second World War.

Recordings of poets such as T. S. Eliot or early Robert Lowell, even the scarcely audible recordings of W. B. Yeats, possess an eerie quality, much as one finds in recordings of bluesman Robert Johnson. Sexton’s readings, however, are anything but ghostly. Although sounding from the gray stone halls of Bedlam, her voice conveys a very direct, matter-of-fact presence. It contains more of the ennuyé shopkeeper than the Sibyl, her tone more housewifely than haunting. This is all the more disturbing. To hear her intone in a raspy New England accent “I come to this white office, its sterile sheet, / its hard tablet, its stirrups, to hold my breath / while I, who must, allow the glove its oily rape, / to hear the almost mighty doctor over me equate / my ills with hers / and decide to operate” is actually quite disturbing. The calm voice belies the naked horror behind the poems. She had to play it cool, particularly when reading before audiences (some of the recordings are from live performances) for various reasons. It was the tenor of the times, first of all, to be cool; second, she saw herself as the seductive, dissolute artist, wearied of the world, ready, almost, to depart it, or at least to try again. On October 4th, 1974, she was successful in this. After lunching with the poet Maxine Kumin, she corrected the galleys of The Awful Rowing Toward God, poured a glass of vodka, put on her mother’s mink coat, and went to the garage where she started her car and placed a brick on the gas pedal.

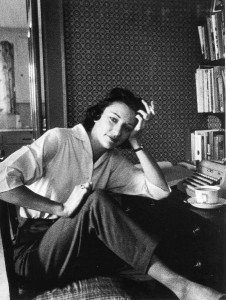

Sexton was as ambitious as it is possible for a poet to be. Although she lacked the precise, classical education of Sylvia Plath, she did spend an enormous amount of time in classrooms, with John Holmes at Boston Center for Adult Education in Harvard Square and with a deteriorating Robert Lowell at Boston University. Having taken up poetry at the suggestion of her therapist, she quickly befriended a number of other poets in these semi-formal settings, including Maxine Kumin (who would be come her closest literary confidant), Peter Davison, and Sylvia Plath (Peter, Sylvia, and Anne would gather over martinis after the Holmes seminar, a short-lived literary circle that Sexton made a great deal of later). Boston in the late 1950s presented an exciting world for aspiring poets. Peter Davison forcefully portrays the era in his book The Fading Smile: Poets in Boston from Robert Lowell to Sylvia Plath. In his telling, Sexton always seemed to be in the room, dangling a long cigarette from her fingers, elegant and nearly starved in appearance, sexy, enthusiastic, and often hazardous to herself and others.

The recordings in this series date largely from her later period, when she was adored and perhaps sometimes feared by her readers, many of whom may have glimpsed their own tragic self absorption in her potentially noxious blend of caustic assertion and infatuated self-awareness. All Sexton cared about, it seems, was her poetry, and her poetry was, from the start, a treacherous extension of herself, an expression of her own anguish and inextinguishable need for attention and love, none of which could, ultimately, stem her suicidal urges. These recordings bring her poems alive in all of their subdued fury and restlessness, their anguish, and their enduring power to fascinate reader and listener.