As Reviewed By: Ernest Hilbert

Part 2: Randall Jarrell

Randall Jarrell’s poetry and criticism have lately experienced individual resurgences. Even his children’s books, with illustrations by Maurice Sendak, have proven very popular. He is one of a small handful of deservedly enduring authors from the golden age of mid-century American letters, the “Age of Criticism,” one of the men who fought in the Second World War, attended university on the GI Bill, and decided to face European traditions on their own terms. He was a very American writer. He loved his sports cars, his cats, and Hollywood; he wrote some of the best war poems of the century, though he never fired a shot himself; his late career recollections of childhood resemble William Wordsworth’s in their nuance and William Blake’s in their immediate simplicity and subtle complexity.

Randall Jarrell’s poetry and criticism have lately experienced individual resurgences. Even his children’s books, with illustrations by Maurice Sendak, have proven very popular. He is one of a small handful of deservedly enduring authors from the golden age of mid-century American letters, the “Age of Criticism,” one of the men who fought in the Second World War, attended university on the GI Bill, and decided to face European traditions on their own terms. He was a very American writer. He loved his sports cars, his cats, and Hollywood; he wrote some of the best war poems of the century, though he never fired a shot himself; his late career recollections of childhood resemble William Wordsworth’s in their nuance and William Blake’s in their immediate simplicity and subtle complexity.

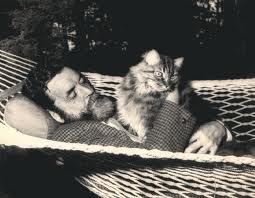

Photographs tell us a great deal about his world. They nearly all show him in domestic situations. Far from the pearled glamor of Anne Sexton or exotic poses of Allen Ginsberg in a white cloak feeding monkeys in India, one finds Jarrell holding the fluffy family cat, wearing gray flannel suits, seated at grassy curbside polishing the hubcaps of his Mercedes-Benz, poised on chair’s arm with Alastair Reid and Robert Graves, in conversation with Robert Lowell at the Arts Forum. If he blazed, it was on paper. He was not, however, an example of the “uptight, plastic fantastic, Madison Avenue” type made famous by the 1956 film Man in the Gray Flannel Suit. He tenderly hosted a ragged Jack Kerouac at his home, escorted Jack (six-pack slung from his thumb day and night) to the Washington Zoo, though Mrs. Jarrell had the sense to conceal their remaining liquor bottles. Author of Poetry and the Age, one of the great books of literary criticism in the past century, Jarrell remained an independent and sometimes brutal critical voice (he said of one book that it seemed to have “been written on a typewriter by a typewriter”), and he took his punches in return (though, as it turns out, he may have had a glass jaw).

Like so many of his generation of American writers, and the generation that trailed them, he suffered nervous exhaustion and attempted suicide. A severe review of one book-commingled with terrible anxiety and the mental strain of a second divorce-led him to slash his wrists open. Robert Lowell, a friend, wrote to comfort and fortify him: “Your courage, brilliance and generosity should have saved you from this.” In the autumn of 1965, while in a Chapel Hill hospital for therapy on his torn wrists, he went for the last walk of his life; he was struck by a car on the edge of a highway and died instantly. This may or may not have been suicide, and the matter is still debated by his devotees. Lowell described Jarrell as “the most heart breaking poet of our time.” It seems that most of the time it was Jarrell’s own heart that was breaking. Like many poets, prized for his delicate observation and aesthetic sense, he was quite fragile when it came to daily life.

The recordings begin with poems written on the subject of the Second World War. Jarrell enlisted in the Army Air Force in 1942 and tried his hand at being a pilot; though he failed to earn his wings, he became a celestial navigation training operator for B-29 pilots. His detailed knowledge of bombers and their pilots proved a serviceable runway for two of his best-known and most harrowing poems, ‘Eighth Air Force’ and ‘Death of a Ball Turret Gunner’. These “war” recordings, delivered in Detroit in 1962, include the rather abstract observations of ‘The Lines’, the sad humor of ‘Gunner’, and the eerily calm ‘A Ward in the States’. As with many recordings, they point up revisions, made on either page or tongue, such as the replacement of the line “All my wars over? . . . It was easy as that!” with the more forceful “All my wars over? . . . How easy it was to die” in ‘Gunner’. ‘A Ward in the States’ immediately calls to mind Wilfred Owen’s description of shell-shocked soldiers from the First World War in ‘Mental Cases’, those “whose minds the Dead have ravished.” Jarrell’s ward is less freighted than Owen’s with deathly cargo, but it is no less gripping. The images are of peace and recovery, yet the ward in which disoriented soldiers rest is “barred with moonlight.”

‘Death of a Ball Turret Gunner’, the poem most familiar to readers of anthologies, is couched in considerable explanation. Given the compression of the poem itself (five lines long), Jarrell’s extempore commentary dwarfs it. Likewise, his grounding for ‘Eighth Air Force’ is extensive. In both cases, the background is welcome. Most readers would not have known, for instance, that the ball turret gunner on an American bomber was often positioned like a fetus in the womb or that at high altitude blood would instantly freeze to the fur-lined jacket. These facts are necessary for complete comprehension of the poem:

From my mother’s sleep I fell into the State,

And I hunched in its belly till my wet fur froze.

Six miles from earth, loosed from its dream of life,

I woke to the black flak and the nightmare fighters.

When I died they washed me out of the turret with a hose.

He doesn’t give too much away, though. The Pilate/pilot dichotomy of ‘Eighth Air Force’ is alluded to simply by way of crediting the Gospels for many of the lines in the second two stanzas of that poem.

An unavoidable characteristic of his natural speaking voice is that Jarrell often sounds as though he is about to weep. This would be an effectual quality if it did not soak every poem. There are other distractions that both add to and detract from the interest of these recordings. In the otherwise “clean” recording of ‘The Truth’, read at Princeton in 1951, an air raid or fire siren goes up midway through the poem and holds its enervating pitch for much of the poem. The trinity of poems written from the perspective of an aging woman, ‘The Face’, ‘Next Day’, and ‘The Woman at the Washington Zoo’, are quite moving given the minor quaver of his voice. The final line of ‘The Face’, “It is terrible to be alive,” is the sort of line that it best to hear Jarrell himself deliver. The last stanza of ‘Next Day’ strikes a commanding chord, at least for the middle class in America:

How young I seem; I am exceptional;

I think of all I have.

But really no one is exceptional,

No one has anything, I’m anybody,

I stand beside my grave

Confused with my life, that is commonplace and solitary.

Jarrell’s consideration of Donatello’s David-a lithe giant-killer poised with foot on the head of Goliath, certainly not the imposingly large and docile David of Michelangelo-is loving in its detailed litany; such a light but erotic treatment brings continued definition to the statue upon which it reflects. The poem seems an act of devotion, particularly its surprising close:

Blessed are those brought low,

Blessed is defeat, sleep blessed, blessed death.

The remainder of the recordings, with the exception of the excellent poem ‘The Player Piano’, is taken up with the three-part long poem ‘The Lost World’, which derives its name from the story of that title by Arthur Conan Doyle and the subsequent 1925 film directed by Harry O. Hoyt. By way of an introduction to his own “Lost World,” Jarrell describes his boyhood journey to school on a double-decker bus, which would take him past the Hollywood studio from whose gates papier-mâché dinosaurs peered menacingly. Much as Doyle’s fantastic notion of a valley untouched by millions of years of evolution is very pleasing in its way (the clumsy use of that title by the Jurassic Park franchise makes no sense, if one thinks about it at all), Jarrell’s notion of a boyhood that remains intact though lost somewhere in time is very gratifying and, in the hands of the adult poet, irresistible.

Certainly Marcel Proust understood that although time cannot be regained, memories may recreate sensations of the past; Wordsworth likewise understood that objects and places fade in the light of age but that with age we are rewarded with wisdom and insight. Jarrell reads ‘The Lost World’, written in conversational rhymed iambic pentameter, with agonizing slowness, and it should be recalled that after the book’s publication he gradually lost control of his life. The little boy surrounded by toy planes and stories of mad scientists has gone. As John Berryman answers his own question in ‘The Ball Poem’, “I am not a little boy.” The adult knows that madmen can destroy the world. He knows now that those toy planes were replicas of machines used to demolish cities. The world has become a murderous place for the grown man, who has attained experience and knowledge, and it is not to be redeemed in reminiscence. This is the world we all inherit:

My universe

Mended almost, I tell him about the scientist. I say,

“He couldn’t really, could he, Pop?” My comforter’s

Eyes light up, and he laughs. “No, that’s just play,

Just make-believe,” he says. The sky is gray,

We sit there, at the end of our good day.

This is the world Jarrell decided he no longer wanted to live in.