I first wrote about Franz Wright’s poetry while working as poetry editor of Random House’s online magazine, Bold Type. Upon publication of his first book with Knopf, The Beforelife, I contacted him for an interview. He agreed, and I sent him a preliminary set of questions. He promptly declined. First-round rebuffs are not unusual for interview assignments. Although deterred, I remained undaunted. Franz and I later became friendly after I met him in person for the first time at the downstairs bar of Makor, on West 67th Street in Manhattan, where he was reading that evening with Sapphire. His editor, Deb Garrison, introduced us, and we hit it off immediately. We shared a morbid sense of humor and a real respect for serious poetry. On another occasion I arranged to have tea with him at the Algonquin Hotel, the famous literary haunt near Times Square. At the chock-a-block outdoor New Yorker Festival readings at Bryant Park that year, he waved me backstage past security (chronically insolvent, I stuffed my bag with fruit and bottles of water from the craft service truck). That evening we attended a New Yorker party, where we encountered the likes of Salman Rushdie, David Remnick, and the magazine’s stable of rather unstable cartoonists. Our acquaintance warmed, and we wrote to each other regularly over the next year or so. When I approached him again about the possibility of an interview, he agreed enthusiastically. He had just won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry and his writing career rose on an updraft that continues to this day, despite his occasional inclination to brawl with critics and battle with magazine editors. On the poetry best-seller lists issued by Soundscan, his last three books have enjoyed successful rankings, placing him among Billy Collins and Mary Oliver as one of the most popular American poets publishing today. Our interview took place over the course of several days and represents, to my knowledge, the most extensive interview conducted to date with Franz Wright.

I first wrote about Franz Wright’s poetry while working as poetry editor of Random House’s online magazine, Bold Type. Upon publication of his first book with Knopf, The Beforelife, I contacted him for an interview. He agreed, and I sent him a preliminary set of questions. He promptly declined. First-round rebuffs are not unusual for interview assignments. Although deterred, I remained undaunted. Franz and I later became friendly after I met him in person for the first time at the downstairs bar of Makor, on West 67th Street in Manhattan, where he was reading that evening with Sapphire. His editor, Deb Garrison, introduced us, and we hit it off immediately. We shared a morbid sense of humor and a real respect for serious poetry. On another occasion I arranged to have tea with him at the Algonquin Hotel, the famous literary haunt near Times Square. At the chock-a-block outdoor New Yorker Festival readings at Bryant Park that year, he waved me backstage past security (chronically insolvent, I stuffed my bag with fruit and bottles of water from the craft service truck). That evening we attended a New Yorker party, where we encountered the likes of Salman Rushdie, David Remnick, and the magazine’s stable of rather unstable cartoonists. Our acquaintance warmed, and we wrote to each other regularly over the next year or so. When I approached him again about the possibility of an interview, he agreed enthusiastically. He had just won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry and his writing career rose on an updraft that continues to this day, despite his occasional inclination to brawl with critics and battle with magazine editors. On the poetry best-seller lists issued by Soundscan, his last three books have enjoyed successful rankings, placing him among Billy Collins and Mary Oliver as one of the most popular American poets publishing today. Our interview took place over the course of several days and represents, to my knowledge, the most extensive interview conducted to date with Franz Wright.

Ernest Hilbert: You were born in Vienna in 1953 and lived in the Northwest, the Midwest, and northern California. Can you say a few words about your childhood?

Franz Wright: My mother (first American-born child of Greek immigrants) and father (middle son of carpenter, factory and railroad worker West Virginian hillbilly Irish) were high school sweethearts who helped each other escape from Martins Ferry, Ohio—across the Ohio River from Wheeling—to the wider post-war world. My father served in the occupational forces in Japan, and then attended Kenyon College, and my mother went to nursing school in Cleveland. My father received a Fulbright scholarship to Vienna, proposed to my mother, broke off the engagement, and then reproposed. They were married, my mother’s father (whose own father, a drunk gambler, had sold him in Paris to some sort of merchant ship captain into virtual indentured servitude for his own fare back to Greece at the outbreak of WWI) banished her from the family, and they took a ship to Vienna, where I was born nine months later, March 18 1953, in their hotel room. During my mother’s pregnancy her mother died of cancer back in Ohio and she never saw her again. In the summer of 1953 we crossed the Atlantic back to the US where I, filled with space and light, was no doubt already addicted to travel or at any rate constant address change. My father attended grad school at the University of Washington in Seattle and studied with Theodore Roethke. My mother worked as a nurse to support us, and my father walked me to nursery school every morning, in the orange shadow of Mt. Rainer—we counted the earthworms which were, due to constant rain, always out crossing the sidewalks, and he sang Schubert’s Die Forelle and various German marching songs and Goethe poems. It was on one of these walks that I am said to have composed and recited my first poem (“I see the shining wind / I see the shining cookie up in the tree”—nice rhythm, good parallelism). Auden awarded my father the Yale Younger Poetry Prize for his first book The Green Wall. Roethke took him to prize fights and they went fishing and drank a lot of beer, and he began his career as an adulterous genius, part psychotic and part saint. He got a job teaching at the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis, where Saul Bellow and John Berryman were colleagues—I remember all these people vaguely—drank more. My parents had an intensely physical relationship (half sex, half fistfights). My mother discovered my father’s love letter correspondence with Anne Sexton, resulting in more fistfights. My younger brother Marshall was born into the maelstrom of their marriage, while I concerned myself with Homer and the Green Lantern. We spent weekends at Robert Bly’s farm in Madison, Minnesota, where I got to ride a horse and shoot things with a .22 caliber rifle in the beautiful woods. My parents divorced. My father had a big breakdown, got fired, got a Guggenheim fellowship and moved to New York; while I—aged 8—and my mother and three year old brother moved to San Francisco, where my mother became a psychiatric nurse. I spent a lot of time wandering around San Francisco by myself and sold my comic book collection (Spiderman #1 is an example of my treasure, which would probably be worth about a million dollars right now) for the first Beatles album. My mother remarried a Hungarian Holocaust-denier who had fought for the Germans and been forced to work in a mine in Siberia by the Soviets and who regularly beat the shit out of me and my brother. We moved to Walnut Creek where I excelled in high school, taking courses at UC Berkley, and purchasing my first ounce of marijuana for $10. I saw the Beatles last concert, at Candlestick Park—I also saw, regularly, Jim Morrison, Janis Joplin, Jimi Hendrix, the young L. Cohen, and read one book—a great book—per day and continued to excel in school hoping to escape from my family, which I did—I traveled in Europe for a year, then came home and went to Oberlin College back—of course—in Ohio. A big strange circle. Q: Do any particular episodes from your childhood stand out for you today? It’s such a vast topic. What immediately comes to mind is finding myself in San Francisco (after the strange cross-country drive with my mother and three-year-old brother) at the age of eight and, being left very much to my own devices beginning to explore, on foot and by bike, that incredible city—this was the early sixties—with great trepidation and loneliness that had something exultant about it. I really had no one to answer to, and that was both terrifying and magnificent. I still feel I could find my way around that city blindfolded. It was really around that time, too, that I discovered that there was another parallel world, the world of reading—the first book I recall really falling in love with was Homer’s Iliad. There was just such a sense of loneliness and loss—I loved my father very much and never stopped grieving the loss of him—combined with this weird miraculous sense of privilege and absolute freedom. Though that loneliness was very painful, physically painful, and along with it my lifelong sense of social ineptness, it gradually transformed into something I loved and treasured and would not have traded for anything. I experienced very powerfully a sense of some special destiny, without having the slightest idea of what form it might take—but for a long time that sensation was enough. I will have to give some more thought to this, I guess. I could be more specific, but the specifics would not be very different from anyone else’s childhood, probably.

EH: You mention that you met many writers through your father. What literary personalities stand out?

FW: Robert Bly is the most vivid. He always seemed ten times more alive than everyone else. It was startling. He was gruff but funny, with children, a lot of fun but serious, intimidating. He showed me how to ride a horse and shoot a gun, and that was big stuff at six and seven years old. I vaguely remember Roethke and Berryman, I was introduced to Sexton, the young Bill Knott—the lovely John Logan, sort of like a drunk saint. When I was visiting him in New York during late high school and during college years, which happened once or twice a year, we got together with Kinnell, Merwin. Dickey was a trip, as I think I have mentioned. Probably lots of other people I am forgetting.

EH: Are you still in touch with any of the ones still alive, like Kinnell, Merwin, Knott?

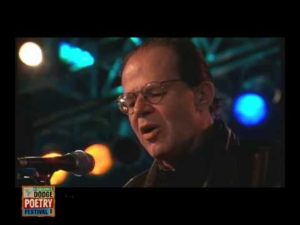

FW: I just saw Galway at the Dodge Festival and we got to talk briefly—a beautiful man. Knott I run into once in a while in Boston or Cambridge, and this extraordinary genius and recluse has never failed to treat me with the utmost friendliness. I am always startled that he recognizes me at all. Robert and I correspond once in a blue moon—a kind of marvelous uncle. These illustrious people have always treated me very well, perhaps partly out of their fondness for my dad. The person who has meant the most to me personally is Donald Justice who just recently died. He is the person I most miss talking with and corresponding with, him and Larry Levis.

EH: You mention a number of concerts from the golden age of rock music. What influence has music had on your writing?

FW: The influence of music on me personally and I hope very much on my writing has been incalculable. That is one incredibly fortunate thing about my upbringing, which, as I think I have hinted, was mostly a botched improvisation on my part, as my parents were too busy being lunatics to be of much practical assistance. However, they did love me, and that is something. Anyway, one wonderful thing was the constant presence of classical music in the house, as my father spent almost as much time listening to it and forcing me to listen to it as he did reciting Shakespeare and forcing me, thank God, to listen to it, until he departed when I was six or seven. I loved music, have always loved and physically hungered for music, of every kind. As a child I used to mentally improvise classical music in my mind to fall asleep—it never occurred to me that this might not be a normal activity, and at four I was playing little Mozart pieces and so forth on the piano, and studied classical and jazz trumpet between ages 10 and 15, when I gave it and everything else up for poetry. The Beatles appeared on Ed Sullivan when I was in fourth grade in San Francisco, and from the first note of that weirdly joyous music I burst into tears and—like every other child in the country—was never the same again. I attended high school between 1967 and 1971 and lived in northern California. I was at Altamont, along with just about every other teenager in the Bay Area at the time. As a teenager, I was of course heavily under the influence of the astonishing range of very great young rock musicians and composers of the time, and remember going to hear Neil Young at Winterland Ballroom a lot, as well as the free concerts the Grateful Dead put on in Golden Gate Park. As an adult I developed a love of every conceivable form of music. There is no genre I am not interested in, and lately it is a lot of sacred music, Bach to Bruckner to Bill Evans to Arvo Pärt. But I listen to and am quite knowledgeable about jazz, and there is still rock and roll. I love Paul Westerberg and would very much like to have a talk with him (we have mutual friends, but have never met). I love West African music. At this moment I am listening to Salif Keita.

EH: Have your poems ever been set to music?

FW: A poem of mine called, I think, “The Wish,” which is about a wish to be a wolf spider and begins “I’m tired of listening to these / conflicting whispers / before sleep . . .” was once sung by, I believe, a Pittsburg group connected with their symphony orchestra at one of the James Wright Festival get-togethers in Martins Ferry, and I have heard that some of my translations from Rilke’s Marien-Leben (“The Life of Mary”) have been, but that’s all I am aware of. A composer named Nathan Pawelek set “Shaving in the Dark” to music, and it was performed last May by the South Dakota Symphony Orchestra—I had an invitation to attend, and wish very much that I could have. Track 5 on the Brooklyn band Clem Snide’s forthcoming CD Hungry Bird is a six-year-old recording of me reciting my poem “Encounter 3 AM”—which will appear next year in Earlier Poems—with a quiet and very lovely Eef Barzelay guitar background or overlay or whatever it’s called. I was skeptical, but in fact it is terrific, chilling really. Q: Outside of music, what influences would you name? From fifteen on, primarily, Rainer Maria Rilke—the poems, the letters, the Notebooks of Malte Laurids Brigge—all of this material ought to be banned to naive teenagers who already happen to live in a sort of nineteenth-century conception of literature and the world, like I did for clinical reasons I do not completely understand, until they are at least thirty years old.

EH: Many of your earlier books are difficult to find. Has there been any interest in publishing a comprehensive book of your earlier work?

FW: A lot of the poems in my first four full-length collections appear in Ill Lit: Selected and New Poems (Oberlin College Press, 1998), a book that has started to sell a little better since it came out that an L.A. rock band named itself after the book (Ill Lit). They are pretty good. I think they’re on tour right now in the west and southwest. But those early books are still around and not that hard to get hold of. I should add that I am trying to get free of my nineties commitment to Carnegie-Mellon University Press (who never distributed my books and never paid me a cent). In another year or so, those three books’ rights should revert to me, and Knopf has expressed some tentative interest in someday doing a big collection, but I may not live to see it.

EH: What are your feelings about the teaching of poetry?

FW: MFA programs have multiplied more than the stars of heaven, that most of them are run by idiots who sit around allowing a roomful of fifteen young writers to subconsciously ruin each others’ best but embryonic impulses by their approval or disapproval, the blind leading the blind. And that the proliferation of MFA programs has filled the country with a fog of mediocrity that has made it virtually impossible to distinguish bad from good poetry. And that what a young writer needs is a mentor—and if he or she can find that in an MFA program, fine, but that the only value of an MFA degree is to allow one to teach in an MFA program—if you can first manage to eat all the other smaller fish who are trying to do the same thing. If you mean the writing of poetry, it can’t be done, but everyone knows that. Of course, there are a lot of things real writers in the same room can teach one another, little always-recalled tricks. And they can have a huge influence on one another, whether through admiration or hatred, I guess.

FW: MFA programs have multiplied more than the stars of heaven, that most of them are run by idiots who sit around allowing a roomful of fifteen young writers to subconsciously ruin each others’ best but embryonic impulses by their approval or disapproval, the blind leading the blind. And that the proliferation of MFA programs has filled the country with a fog of mediocrity that has made it virtually impossible to distinguish bad from good poetry. And that what a young writer needs is a mentor—and if he or she can find that in an MFA program, fine, but that the only value of an MFA degree is to allow one to teach in an MFA program—if you can first manage to eat all the other smaller fish who are trying to do the same thing. If you mean the writing of poetry, it can’t be done, but everyone knows that. Of course, there are a lot of things real writers in the same room can teach one another, little always-recalled tricks. And they can have a huge influence on one another, whether through admiration or hatred, I guess.

EH: How then would one explain the great number of MFA (master of fine arts) programs for poetry in the United States today?

FW: Well, some of my best friends teach in MFA programs. But seriously, I do not understand the proliferation of MFA programs over the past quarter century, and have no opinion about it. It’s a subject that offers endless possibilities for someone like me (who never seemed to be able to fit into any adult real world situation for most of his life) for cheap shots, for example: Can you imagine Arthur Rimbaud taking part in a creative writing workshop? But even I realize how childish that is. I have no advanced degrees myself, but that is not something I am proud of—it just didn’t work out like that for me. I have had a couple opportunities, briefly, to teach, and enjoyed them very much—though I must say I infinitely prefer the teaching of literature courses. That is a hell of a lot of fun.

EH: If you could choose four poets in the English language, from any period, to teach in a course, whom would you choose?

FW: That sounds like one of those rapid free association questions. Ok, before I have time to think about it, right off the top of my head: Walt Whitman, William Blake, Theodore Roethke, and George Herbert.

EH: Along the lines of free association: When I say the word “James Dickey”, what is the first thing that comes into your head?

FW: I don’t know if that’s really fair. Like a lot of poets of his generation he was a more or less hopeless alcoholic and this led him into some deplorable behavior (and look whose talking)—but I believe his best work is fantastically beautiful poetry, and I think it is largely forgotten that his influence on other poets was huge, as big as Robert Lowell’s or then Robert Bly and my father (I think my father was seriously influenced by Dickey, as much as he was by Bly). I think he wrote some truly great poems, in his middle period.

EH: It has been remarked that poetry consists either of moral discourse or visionary observation. What do you think of this statement, and how would your poetry fit into this description?

FW: I think those are both good descriptions. All true poets are visionaries and experience oceanic instances of seamless mingling with the infinite in the face of everyday things (astronomical perceptions, as Blake and Lorca put it, in the contemplation of very small concrete things; or as Flannery O’Conner said, only in and through sense experiences does a writer approach a contemplative knowledge of the mysteries they embody); and of course poetry, of all arts, is the most moral if we keep Kant’s definition of morality in mind, as that act for which no possibility of compensation really exists. There is nothing to be gained from writing poetry (and everything to lose, come to think of it) if it is truly taken seriously.

EH: Your poetry often treats subjects such as emotional and physical recovery. Can you say something about your choice of this subject?

FW: Well, I guess the famous dictum is “write what you know.” Actually, I have always believed it should be the exact opposite, and wish very much that I could be more like, say, René Char, and spend more time in the lyrical absolute than in my wretched personal concerns—and I think I am making a little progress!—but it is the inescapable fact that my life has involved a sometimes nearly lethal struggle with drugs, alcohol, and mental illness (as well as sex and rock & roll, during younger years). I’m a pretty regular baby boom kind of guy in that respect, I suppose. But I think it is also true that from the very start poetry represented for me a way out of a very dark and hostile world into a radiant and serene one, so even when the poems seems to be very dark, I did not experience them that way: I experienced them as blessed moments of escape and relief from my self.

EH: Some poets, like Geoffrey Hill, claim never to have been disappointed by anything they have published. Others, like Ezra Pound at the end of his life, have experienced an incredible sense of remorse. Have you ever regretting something that you have published?

FW: Approximately 90% of it.

EH: You have written poems in what might be called a darkly humorous mode, such as “Body Bag,” from your collection The Beforelife, which consists of a single line: “Like the condom in a pinch one size fits all.” Your work is generally very serious. What role does humor play in your work?

FW: I don’t know. Some people seem to find my most serious poems funny, or they’re enraged by them, or something. But never mind that. The parts in my poems that are funny just seem to appear at certain moments—maybe there is a sense in many extreme situations where humor is the only appropriate response to the horrific, a sanity-protecting thing kicks in. One thing I will say about this is that it may have originated in an attempt to emulate James Tate, whose “funny” poems are sometimes his most terribly poignant. I think he is an inimitable master in this regard.

EH: There are famous stories of Ernest Hemingway sharpening pencils and lining them up on his desk as a way to prepare him emotionally and mentally for the start of the writing day [he denies this in his Art of Fiction interview with the Paris Review, but it serves as an example of possible writerly ritual. – E]. Do you have any rituals that help you to write?

FW: I generally won’t even attempt to write anything down unless I feel a genuine upwelling from (for the more secular minded) the subconscious or an infusion of necessity or energy from above. But yes, there is one thing I still do, which is take a walk, at least an hour, someplace I feel comfortable and safe and happy. I have a number of these fortunately in the town I now live in, west of Boston, Purgatory Cove along the Charles, a very beautiful cemetery not far from my house, Walden Pond or Flint’s Pond in the Lincoln Woods about a twenty minute drive away, and so forth. Words are often generated by walking, for me.

EH: What is your usual technique of composition?

FW: It usually starts with a fragment that occurs—mentally—and which I carry around in my mind for a while to see if anything else is going to come before setting it down in one of the little pocket notebooks I always carry (this often involves furtive and evasive procedures like going to the men’s room, or hiding behind a tree or something). I transfer fragments to bigger notebooks and to typewritten sheets, which accumulate over time—I really use any means available at that point, typewriter, computer. I still prefer working longhand in a notebook, but then certain technical advantages emerge when you got to type something, I find.

EH: Do you compose in lines, mentally, as William Wordsworth did, or do the lines emerge from the larger written form only later on the page, as one finds when looking at the manuscripts of W.B. Yeats, who usually began with a block of prose?

FW: The fragments tend to fall very quickly into verses, since I don’t take a real interest in them unless they possess a certain rhythmic and musical quality as well as imagistic or intellectual quality.

EH: You have remarked in the past that you sometimes have the sensation that a poem comes to you as a unified whole all at once, while you are walking or in another meditative state. Is this true?

FW: It has certainly happened, but it is rare, of course. Just the other day I wrote a poem of about fifteen lines, one I am very pleased with, just about as fast as I could get it down, a few minutes maybe. They do occasionally appear fully formed. But again, this is rare. I have very often spent years on poems. I once spent six years on a five-line poem.

EH: What do you think of poetry in the United States today, opposed, say, to twenty or thirty years ago? What has changed?

FW: I’ve gotten sort of old and grouchy and set in my ways and tend not to read that much anymore (except a few books by people who lived hundreds or thousands of years ago), and I think this is partly because being obsessive about writing poetry kind of ruins the magic of reading it. I don’t enjoy reading it the way I did twenty and thirty years ago. I know there are a hell of a lot more people writing it (as Richard Howard quipped, more people write than read poetry now) and that there is a dizzying array of groups or cliques or schools of poets. But maybe that has always been true, and as there are so many more human beings on the planet now, there is a commensurate increase in the number of people foolish or suicidal enough to want to be poets, I mean in the United States of America. There are of course cultures, in which there is some degree of prestige attached to being a poet, but ours is not one of them, and the reason for that is that there is no money in it, which makes it somewhat suspect in our eyes.

EH: If you could change one thing about literary culture in the United States, what would it be?

FW: I really don’t have the faintest idea—maybe wish writers and reviewers of poetry could be less petty and prejudicial and more generous, open minded and spiritual, which is absurd and sounds a bit like saying I wish for peace on earth, and the coming of the kingdom of heaven. It’s never been that way and never will be, except in the hearts of certain rare individuals (and I am certainly not claiming to be one of them). And maybe a certain degree of hostility isn’t so bad, it may help younger people form their own critical sense.

EH: Do you have any particular critics or publications in mind when you say this?

FW: One immediately comes to mind, the New Criterion, and their main spokesperson William Logan (who should really learn how to write prose, by the way). My idea is that they should start a literary version of one of those rightwing talk radio shows. That way they could reach many more young reactionary unpublished paranoids who are convinced a vast conspiracy exists to keep them from being read, and this might serve to somewhat quiet the malicious and envious hatred that keeps them awake at night gnashing their teeth at the thought that someone out there might have a few people reading his books. Logan in particular never bothers to write about anyone with his inimitable spirit of hatred and mockery unless the writer gets a certain degree of attention, and in this way he is oddly snobbish. But think of being a most ignored and mediocre writer, both of verse and prose, who has to teach English at the University of Florida in Gainesville. I suppose he should be pitied. See what a tolerant person I am?

EH: Are there any literary magazines, newspapers, or other reviews you read regularly?

FW: Not that regularly, no, though I still try to keep up with a couple, like Field, which comes out of Oberlin and reminds me of my college days and my beloved teachers David Young and Stuart Friebert. I think they still do a hell of a job combining established poets with unknown very promising ones. They also begin each issue with a symposium on a particular poet, either American or European, with excellent and thoughtful and generous essays by real writers, as opposed to illiterate and highly opinionated hacks, who really out to be writing for British tabloids or something.

EH: Can you name three American poets writing today, of any age, who you admire?

FW: Fanny Howe, Olga Broumas, and Jean Valentine.

EH: All women here, but when asked about your four ideal poets to teach in a class they were all “dead white men,” so to speak (Walt Whitman, William Blake, Theodore Roethke, and George Herbert). How do you explain this discrepancy between the living and the dead?

FW: I just mentioned those four off the top of my head. On another day, it might have been four others. And I certainly see no distinction between great male and great female poets. You’re a poet or you’re not (and if you’re not, count your blessings).

EH: In many ways, two important poetry editors have championed you, Deb Garrison at Knopf and Alice Quinn at The New Yorker. Can you comment on your relationship with them?

FW: I think they are both utterly brilliant and dedicated editors, with a genuine gift or calling to do what they do. In my personal case, I can’t tell you how many times they have improved a poem of mine with a single glance and suggestion, immensely improved it. They have the eye. In any field (education, medicine, sports, etc.) you get a lot of competent people at work, but a few will stand out as genuinely gifted, genuinely called to do their work. And I think Alice Quinn and Deborah Garrison are like that.

EH: What role should an editor play in the life of a poet?

FW: Certainly it should be different from that of an historian or a novelist. I’ve been fortunate with editors. The other one who stands out is David Young, in that they have become friends and, when necessary, counselors in a sense. People I can turn to for advice.

EH: What differences are there between publishing with a university press like Oberlin and a commercial publisher like Knopf, which is part of Random House, which in turn is part of the international media conglomerate Bertelsmann?

FW: You get more publicity, better distribution, so you do tend to sell more books. And you get more reviewer attention. And I have to say the snobbery of reviewers and places like Publishers Weekly, and other such magazines, astounds me—they never paid the slightest attention to my work until Knopf published it. Actually, it must have more to do with ignorance than snobbery. As everyone who knows anything about contemporary poetry knows, a good deal of the best work is published by small or university presses (while a good deal of absolute shit is published by major publishers)—but I suppose you have to know where to look or be into it enough to know where to look.

FW: You get more publicity, better distribution, so you do tend to sell more books. And you get more reviewer attention. And I have to say the snobbery of reviewers and places like Publishers Weekly, and other such magazines, astounds me—they never paid the slightest attention to my work until Knopf published it. Actually, it must have more to do with ignorance than snobbery. As everyone who knows anything about contemporary poetry knows, a good deal of the best work is published by small or university presses (while a good deal of absolute shit is published by major publishers)—but I suppose you have to know where to look or be into it enough to know where to look.

EH: And what are your experiences with independent presses, ones even smaller than university presses?

FW: I don’t know what to say about that except many of my favorite books over the years have come out of independent small presses and are now even more precious as they are impossible to find anymore. An example from hundreds that comes to mind is Cid Corman’s masterpiece of a translation from Char’s Leaves of Hypnos.

EH: Tapping the White Cane of Solitude, was published by Triskelion Press in 1976. How did it come to pass Triskelion published your first book?

FW: Triskelion was a small, handset type press run by David Young (and editor of Field and professor at Oberlin College) and another professor there, Dewey Ganzel, the Twain scholar. I was a junior at the time, 1976, and David suggested we do a chapbook, as I’d been publishing poems for several years.

EH: The Earth Without You was published by the Cleveland State University Poetry Center a year later. The One Whose Eyes Open When You Close Your Eyes was published by Pym-Randall Press the next. Going North in Winter was published by Gray House Press in 1986. Entry in an Unknown Hand was published by Carnegie-Mellon University Press in 1989. And Still the Hand Will Sleep in Its Glass Ship appeared from Deep Forest in 1991. Midnight Postscript (1992); The Night World & the Word Night was Carnegie-Mellon again, in 1993. Ill Lit: Selected & New Poems appeared from Oberlin in 1998. Then we have the two from Knopf, The Beforelife and Walking to Martha’s Vineyard, for which you won the Pulitzer Prize. How do you explain the range of different publishers you have used?

FW: You forgot Rorschach Test, another Carnegie-Mellon book, maybe the best of them but probably also the most disturbed. I don’t know, I think deep down I just never believed it to be worth the trouble to even try sending a manuscript to a major New York press, and so never even tried. Whenever someone expressed interest, I would just let them have the work, and somehow someone always did. Carnegie-Mellon was a good place, and Jerry Costanzo, the main editor there, cared very much about the books and did a good job with them but was unfortunately unable to pay me any royalties or to distribute the book—don’t think I ever once saw a copy of any of those books on a shelf in any bookstore. That never happened, in fact, until The Beforelife appeared in 2001. My wife and I used to go into Cambridge and walk around to various book stores just to look at the strange fact that I had a book on a shelf in a poetry section. It seems funny and pathetic now. Ill Lit, from Oberlin College Press, got around a little better, though not much, but it felt good to be back with people I was friends with and knew cared about me.

EH: You have several chapbooks as well. Hell & Other Poems appeared from Stride, in the UK. God While Creating The Birds Sees Adam In His Thoughts was issued by David Dodd Lee. How do these projects get started?

FW: Somebody writes to me and expresses an interest in doing a small limited edition chapbook, and if I have work on hand—say I am in the middle of working on a book, which come to think of it, I suppose I always am—I say, sure. I love those little books. I think in some ways the ideal book of poems is twenty poems. Though saying that, I am reminded that I am now trying to finish one that is over one hundred poems long right now. I am trying to figure out a way to produce a longer “statement” which also works as a whole, not just a miscellany of poems.

EH: Some of your other books prove a bit more elusive, such as the early 8 Poems, Midnight Postscript, and Knell. Can you tell me where these appeared?

FW: New York, New Hampshire, and Minneapolis. 8 Poems was a Xeroxed and stapled pamphlet done by my dear college friend Dan Simko who died a couple months ago in NY—someone pointed out a rare books online service offering it for sale for fifteen hundred dollars or something like that recently. I remind you, very few people took much notice of my work until about three years ago—it is very strange.

EH: You are married. Is your wife also a writer? How has she affected your writing and your life in general?

FW: She’s quite a good writer, an excellent writer, and a very gifted translator who is official American translator of a number of fascinating contemporary German poets. She literally saved my life, took me on when I was still in a state of psychotic depression (which lasted nearly three years) and made it clear she would have stayed with me even if I had remained a semi-invalid. Brilliant woman, and an absolute babe.

EH: How has winning the Pulitzer Prize changed your life?

FW: I think it has made me a more confident person, it seems easier to hold my head up in certain social situations—not literary ones, necessarily, but just normal ones. It’s helped me sell more book and get readings, and that helps me make a living, such as it is. Psychologically it has helped me feel a bit less overwhelmed by my father’s shadow, that sort of thing. I consider it a great honor, and it still amazes me, and I think it will always amaze me.

EH: Your father won the prize as well. Are you the first son of a winner to take the prize home as well?

FW: Yes, that’s what I have been told.

EH: The Pulitzer Prize is a widely recognized award, due in part to the great emphasis journalists themselves place on it. Do you get the sense that the prize somehow legitimizes the practice of poetry to our society at large?

FW: I really don’t know. But maybe this is my chance to say that poetry’s unimportance in this country may not be such a bad thing. It maybe has helped, in some oddly Darwinian way, to give it its greatest moments. Antionio Porchia said somewhere, the truth has few friends, and they are suicides. To devote yourself, I mean really devote yourself to poetry in the U.S.—it does (in spite of the usual flood of mediocrity, or half measures) tend to separate the nuts from the shells.

EH: You are about to read at the Dodge Poetry Festival, the largest in the country. What are your feelings about public readings?

FW: I don’t mind reading, and actually—I am thinking of my one participation in the New Yorker Festival in Bryant Park—I think it is easier to read in front of thousands of people. It’s the readings where five people show up that are tough. Anyway, the whole thing is very unpredictable, for me. Sometimes I’m up for it, and do pretty well—sometimes I make a fool of myself, for some reason, or that’s what it feels like. My feeling is that the public reading of poetry is basically a mistake—but then I think of the excitement I felt when young at getting to see and hear a poet a greatly admired. I think there is one danger inherent in poetry readings as we know them. I think there is a danger that the poet will be subconsciously affected, or his writing will be, by the kinds of responses he gets from an audience. We long to be loved and admired, no matter how strong someone is, or self-reliant, I think this is true—and if you notice that a certain type of poem goes over well with an audience, there may be an unconscious (or perhaps quite conscious) tendency to continue writing in that vein, and then you do not grow and your work may not develop and deepen in the same way it did while you were writing to no audience, no applause, no chuckles. I can think of poets whose work has suffered because of too early success in this way, too many readings, too much exposure to reading audiences.

EH: Has the culture of public readings given too much attention to performance and personality over poetry? Is there even a division between these?

FW: I don’t know, but I think poets should be as solitary and invisible as possible—no problem there, really. Since poetry, like crime, can only be accomplished in absolute privacy and secrecy. (Even prayer is something people can do together.) But what the hell, why shouldn’t poets get out and get a bit of attention or even adulation, and make some dough at the same time? I find that as long as I am sober, I can handle the scene, and then just go home and return to being my normal wretched, lonely and sometimes euphoric self. I really don’t have that much experience with all this, haven’t, until now, given that many readings or attended more than a handful of them.

EH: When James Schuyler, formerly a bit of a recluse, finally gave his first big public reading at the Dia Center in 1988, the crowd was large and very eager to hear him. Many younger poets remark on how important this reading was for them. Have you enjoyed the readings of any particular poet in this way?

FW: When I was sixteen or seventeen I drove from Walnut Creek into San Francisco to the San Francisco Art Institute to hear Robert Bly read, and what actually happened was that he appeared with a big stack of books by other poets and proceeded to read from them and comment on them with a passion I have never before witnessed in any poetry reading I have attended. I think that made an impression on me that has remained indelibly as an example of the power of love for poetry and an ecstatic readiness to be of service to it. I should add that the young Andre Codrescu (this was about 1969 or 1970) happened to be in the audience, drinking a bottle of wine and his lively and erudite interjections livened up and added tremendously to the whole thing—it must have gone on for a couple hours—an exciting time. Afterwards we went to a party somewhere, and I found myself surrounded by many poets I was in awe of—I think Ginsberg and Bill Knott (I may be imagining this) might have been there as well, though very quietly—and remember overhearing Robert and Andre comparing notes on the benefits of fucking in the snow and so forth. This was some wild shit for an extremely shy but poetry-obsessed teenager.

EH: Do you feel any anxiety before your own readings? I feel great trepidation, usually, right before my own readings, but a strange wild excitement as well. And I have learned, over the years, I think I have learned how to convey my passion for poetry in a reading. Usually they go fine—though I have memories of some that are searingly embarrassing to me still.

EH: What can go wrong in a reading?

FW: Well, it’s not like someone’s going to stand up in the back and say, “That line sucks!” But you can tell. You can feel when you are getting through to people in an audience, whether there are five of them or three thousand—and you can definitely tell when you aren’t, and it is then you sincerely wish to get down on your hands and knees and crawl off the stage. I should add that I have gotten much better at it recently, maybe from doing it so much. I am much calmer, and somehow that helps me be more passionate, as opposed to hysterical. When you’re frightened about what people think, you’re lost.

EH: Oscar Wilde wrote, “All bad poetry springs from genuine feeling.” This was a standard witty inversion for him, but he was convinced that style trumped all else. Is it possible for a poet to succeed artistically without depth of feeling? Must one feel extremes of pain or love to create authentic poetry, or is stylistic capacity enough?

FW: You must have both, clearly. And have them to a terrible, excruciating and obsessive degree.

EH: What of an evasive and coolly disposed poet like John Ashbery? Is he somehow incomplete in this regard?

FW: I’ve always imagined him as being a rather impassioned writer—the stuff is torrential no matter what else one may think of it. And I do happen to think he is a very great poet. It’s just not my thing. The earlier stuff, yeah.

EH: If someone were blindfolded and reached out at random on your bookshelves, what might he come away with?

FW: The New Testament, Neue Gedichte, and the pornographic stories of Apollinaire.

EH: What is your advice to a reader who would like to become familiar with modern poetry?

FW: My advice would be read all the great poetry that preceded it first.

EH: But there’s so much. It would take someone years just to get through the big names in English poetry. Wouldn’t this tactic discourage a new reader?

FW: If they had no interest in reading previous poets—even if they only went back to the seventeenth century and the Romantics—why would they wish to read the poetry which was largely written in response to or in reaction to it? Besides, there aren’t really that many great poets, are there?

EH: If Hollywood were to make a movie about the life of a poet, which one would be the most interesting?

FW: They already have—did you ever see that one in which Leonardo DiCaprio plays Rimbaud? It was actually rather touching, in an idiotic way. The whole idea is horrifying, and I’m glad poetry is so unpopular here that it hasn’t often occurred to them. The one about Iris Murdoch was good. I steered clear of the Plath one, but then I steer clear of anything relating to her extremely promising but almost infinitely overrated work.

EH: If they made the story of Franz Wright, who would play you?

FW: Laurence Olivier.

EH: How important are stories to you, when it comes to poetry? I’m not thinking of narrative poems, as such, but stories that can be used in a poem to perhaps drive a larger philosophical or poetic point.

FW: I don’t know about stories. I do know there are brief intense moments in life that are instantly recognizable as somehow cosmically symbolic or significant, or—and they usually involve great suffering—are clearly occurring as terrible and unavoidable teachings. Sometimes, later on, years later usually, when the pain of them has faded, they can be written about.

EH: I would like to take a single, extended line, from the poem “Year One,” in your most recent collection, Walking to Martha’s Vineyard: “Moonlit winter clouds the color of the desperation of wolves.” How did you arrive at this image?

FW: My brother and I came up with it together during a conversation in a mental hospital in California in 1989, where he was staying for a while. I think we had taken LSD.

EH: Is it unusual for an image to stay with you for that long before it appears in a poem?

FW: I think that must be nearly a decade and a half after its inception that the line appeared to the public. Happens all the time. Image in search of a context, again in the Glückian sense. I keep many, many notebooks—and am blessed with or inherited a kind of semi-photographic memory from my father.

EH: At the end of a poem, Allen Ginsberg would sometimes cite the drugs he had taken while writing it. What effects have drugs of all kinds—even coffee, cigarettes—had directly on your writing?

FW: It had a huge effect, for about twenty-five years, but largely a negative one. One of the most sinister things about addiction is that in its initial stages, in the early years, it seems to produce a state resembling religious enlightenment, or a Blakean sense of the infinite in the small and particular, the eternal in the moment. And this is the right thing to be looking for, but drugs only produce the delusion of having this experience, and pretty soon (if you’re made that way) you start needing them just to leave the house and function in the world, forget about visionary sensations. The other effect they have—Ill Lit is a good example, Berryman’s Dream Songs are an immortal one—is that they may lead you into writing what amounts more or less to a textbook on what it’s like to be a narcissistic and terrified psychotic.

EH: I’m going to give you some quotes, and I would like you to respond to them in any way you like. The American literary critic Burton Rascoe once wrote that “what no wife of a writer can ever understand is that a writer is working when he’s staring out the window.”

FW: I am blessed with a wife who understands that quite well—perhaps because she is a lovely writer herself. Sometimes she will glance at me while we are driving or eating dinner and say something like, “Writing again?”

EH: Robert Frost said “A poet never takes notes. You never take notes in a love affair.”

FW: The statement and its silly analogy both strike me as inaccurate.

EH: Walker Percy thought that “a good title should be like a good metaphor; it should intrigue without being too baffling or too obvious.”

FW: That’s lovely—hard to improve on that.

EH: Toni Morrison said, “I always know the ending; that’s where I start.” Does this relate at all to your style of composition?

FW: I know what she means, but in my case, for most of my so-called career I seemed almost to cultivate a deliberate unconsciousness as to subject material (I think I have become a good deal more conscious of what I want to say now, though not too conscious I hope)—language, phrases, images, lines come to me in a fairly random way and after a while accumulate and begin to suggest what Louise Glück marvelously described as a context. Somewhere very near the end of composition process I become aware of a subject or context or something, and then can bring conscious faculties to bear. But if I’m not a bit shocked or moved myself by what occurs, I consider the whole effort a failure. I have noticed, technically, that a good poem has the look of a single correctly spelled word, symmetry and something very satisfying, like good shoes.

EH: Maurice Valency said, “failure is very difficult for a writer to bear, but very few can manage the shock of early success.”

FW: I was lucky—I had some early success, beginning to publish at 18 and having a little book while I was still an undergraduate—but it was not the sort of overwhelming success that, say, Jim Tate dealt with so well, and that others have not dealt with so well.

EH: Commenting on his reasons for giving up boxing when in college, T.S. Eliot wrote, “I was too slow a mover. It was much easier to be a poet.”

FW: I think many things Eliot said, when he was aware they would be quoted, were meant to throw people off his track. I wonder if there has ever been another poet so politically concerned with his reputation? Not that this makes him any less great as a poet—any more than being a practically psychotic addict lessened the magnificent humanity and visionary powers of, say, Baudelaire or Berryman or Hart Crane. But Eliot was probably such a passion-torn (far more than Yeats, who talked about it so much) and guilt-ridden person, it is no wonder he resorted to these sorts of charming quips and evasive tactics.

EH: Stephen Spender wrote, “Great poetry is always written by somebody straining to go beyond what he can do.”

FW: Aside from its perfectly clear literal meaning, it reminds me of the experience I always have upon completing what I consider to be a successful poem. First I get down on my knees, in reality or in thought, and thank God. But even then, in the back of my mind, I am rejoicing at having hit upon the formula, the way to write the poem. But as soon as I try to apply it, I immediately discover it won’t work, that it’s as if I had suffered a stroke and have to learn how to write all over again. Every poem is an attempt to write The Poem, and is a failure.

EH: Religion seems to be central to your writing. Can you say a few words about how religion has affected your life and your view of the world?

FW: My religious faith is very real and literal, almost to a childlike degree—though with my ancient skepticism and dread of abandonment thrown in—and I can only say it has made it possible for me to go on living. I would not have been able to go on living otherwise.

EH: Could you write without this faith?

FW: Sure, but it would be the same old lurid and sensationalistic in-love-with-death or oblivion crap I wrote so much of. But the point is, I very likely would not be around anymore to write anything at all. Not that that would be any tremendous loss to letters, as they say. Part of what makes it possible to go on writing is an intensely acute sense that it is not just the poem but what the poem is pointing to, and that it’s all going to go, all of it, Shakespeare, Homer, Basho, everything—the sun itself will die, and all will return to whatever it is, whatever Light it emanated from to begin with.

EH: What poems about God or religious faith do you feel are particularly important?

FW: The poems of the skeptically religious—of, for example, Blake, Rimbaud, Hart Crane, Rilke—often feel more satisfying to me in this way than the more obviously religious poets like Donne or Eliot or Hopkins or lot of others anyone could mention. You know who is really interesting in this way is George Herbert, who so clearly a believer yet whose whole work seems to amount to a serious doubt about his worthiness even to speak of or to God. That is especially poignant to me.

EH: In his poem “Affliction III,” Herbert writes: “My heart did heave, and there came forth, ‘O God!’ / By that I knew that Thou wast in the grief, / To guide and govern it to my relief, / Making a sceptre of the rod.” Can you say something about those lines?

FW: It reminds me of something Louise Glück wrote in her last book, and I am not quoting it correctly but it amounts to: “I am the light, your anguish and humiliation—did you imagine another? There is no other.” [Editor’s note: This is from the poem “Stars” in her collection The Seven Ages, Knopf, 2001: “I am the light, / your personal anguish and humiliation. / Do you dare / send me away as though / you were waiting for something better?”] I think what Herbert is getting at (Hopkins is marvelous at this, too) is that our suffering is the terrible and only teacher—Kierkegaard said famously suffering is the characteristic of God’s love—and I think everyone senses that failure and brokenness and loneliness cause us to perceive us as God might, as naked and ignorant and blind. Our suffering may be the real form love takes, but we also know that at the end of it waits infinite peace and radiance, that has been my experience anyway. Why things are arranged this way, who knows—pretty soon we are all going to find out.

EH: Yes, the Kierkegaard epigraph to your selected poems Ill Lit is “one must never desire suffering. No, you have only to remain in the condition of praying for happiness on earth. If a man desire suffering, then it is as though he were able by himself to solve this terror—that suffering is the characteristic of God’s love. And that is precisely what he cannot do.” Can you talk about that a bit more?

FW: It reminds me of the big misunderstanding, especially in certain forms Christianity takes—the mortification of the body to approach the spiritual side of one’s being, as if further mortification than what is daily offered us, for free, were not enough. It’s like the difference between anorexia and true selflessness or self-denial. Rilke has a wonderful remark about this: “Asceticism, of course, is no solution: it is sensuality with a negative prefix. For a saint this might become useful, as a kind of scaffolding. At the intersection of his various acts of renunciation he beholds that God of opposition, the God of the invisible who has not yet created anything. But anyone who has committed to using his senses in order to grasp appearances as pure and forms as true on earth: how could such an individual even begin to distance himself from anything! And even if such renunciation proved initially useful and necessary for him, in his case it would be nothing more than a deception, a ruse, a scheme—and ultimately it would take its revenge somewhere in the contours of his finished work by showing up there as an undue hardness, aridity, barrenness, and cowardice.”

EH: Some critics have referred to the extreme uses of drugs and alcohol among artists a form of “inverted asceticism.” Is there anything to this?

FW: Well, like I said before, drug use among artists is the catastrophic and incredibly obvious mistake of looking for the right thing, illumination, in the wrong place—as if the chemical contained what was necessary, when all along it is within us, obviously. The problem is it takes a lifetime of discipline to access that state of illumination—it must be sought, found, then constantly maintained—and with drugs at first you get the impression that it’s something you can turn on and off with a switch. But it is understandable—the world is so awful, and artistic aspirations go so against the grain of things as they are, it is natural to despair, in the midst of so much ugliness and chaos, of finding any other way to enter that other state, that other place of illumination. And the other horrible problem is that it sometimes really works, initially—if it didn’t work, to some degree, it wouldn’t be such a problem.

EH: Have you ever been interested in writing criticism, reviews, or perhaps a memoir?

FW: I won’t write a memoir, but I have some ideas for essays actually, and would like to try to put together a book of them—but we’ll see. I feel there are so many more important things I need to do—and I don’t mean writing more poetry—and time is short.

EH: If you could speak to one writer in history, actually sit in the room with them for an hour, whom would you pick?

FW: Any of the writers I might choose, I don’t think I could bear sitting in the same room with. My father was about as much as I could deal with, that was sufficiently awe-inspiring and as much love as I could endure.

EH: Any other historical figures, aside from writers, who you would like to meet and engage in conversation?

FW: I would like to meet Jesus, but I would certainly not wish to engage him in conversation—I would like to follow him everywhere he goes, at a great distance, far enough away to keep an eye on him and to be able to hear a little of what he says (or find out from somebody closer to him), and hoping very much not to be noticed by him.

EH: Why not to be noticed? What would happen?

FW: I don’t know. It’s a hard thought to cope with. Maybe the George Herbert dilemma again—one feels, how can I possibly be worthy of God’s attention, and on top of it, maybe it would be best—considering the way I have spent most of my life—not to be noticed at all. When all the time unqualified love and mercy and forgiveness are precisely what we are being offered.

EH: Are you a Catholic?

FW: Yes. I ought to add that I was only baptized a bit over three years ago. And that I often attend Greek Orthodox services, as well as trying to get to Mass every morning, and that I practice certain forms of Buddhist meditation and have a lifelong interest in that—for several years as a teenager, I studied Zen Buddhism seriously with a Korean Zen master in Berkeley.

EH: What position does the Church take on the role of the poet in society?

FW: I don’t know. I can say the priests and other parishioners I have come in contact with have taken a very lively interest in the fact that I am a poet—so much so that I wish I had kept this to myself sometimes.

EH: Do people treat you differently after they learn that you are a successful poet? Do you every find people expecting a certain type of behavior or wisdom?

FW: I guess that happens in certain public situations, like the recent Dodge poetry festival [Editor’s note: the interview was begun before he had read there, and continued afterward], or sometimes with certain people at readings, but not too much—not among people I’m in daily contact with.

EH: What are you working on at the moment?

FW: I have a new book of about 100 poems called Prescience. It begins with a 200-line poem that deals with the place I found myself back in 1996, just before entering a two-year period of psychotic silence, frankly. Thought it is about a bit more than that. It should appear one of these days before too long. Deborah Garrison and I are just beginning the editing process. [Note: The long book was retitled God’s Silence and issued by Knopf in the late spring of 2006. There are plans to publish his first four books of poetry as Franz Wright: Early Poems in 2007, also from Knopf.]

EH: Do you intend the word “prescience” as a title for your new book to refer to divine omniscience or simply to a foreknowledge of future events?

FW: First, I should add when I said it is due to appear soon, I meant in the pages of The New Yorker. As to prescience, I like the word on the page because it looks like pre-science as well as meaning the ability to know of things before they occur or whatever. I am also using it because it as title of what I consider—though it is a fairly inscrutable poem, and quite formal, in its way—to be the central poem of the collection. It appeared last February in The New Yorker while I was down in Fayetteville. I don’t know what else to say about that. I think sometimes I will use a title to draw attention to a particular poem, though, and that may be true in this case. Also, none of this is written in stone. I may very well change the title at some point, though I doubt it.

EH: Allen Ginsberg would sometimes rewrite poems for decades after their first publications. His books went through many printings, and he was so lucrative for Ferlinghetti’s City Lights Books, that he could change poems each time they appeared. Do your poems continue to go through changes right up to the publication of a book? Do you ever wish you could change something after it appears?

FW: Not very often. Though when I got the opportunity to do a selected from my first four books (along with translations and some new poems) in Ill Lit, I quite radically revised some of those poems. It was very enjoyable, like getting to work on somebody else’s poems.

EH: Are there any other projects you are looking forward to attacking?

FW: I am dreaming of a book of essays. And I would like a new translation project. I have always secretly longed to work on Johannes Bobrowski, the great post-war East German poet, a sort of updated [Georg] Trakl who commemorated some of the disappeared Jewish communities and villages in eastern Europe—which, I suppose, he had an involuntary hand in making disappear, like Gunther Eich, another very major and magnificent post-war German poet who found himself faced (in a way different I think from Paul Célan, since he was more a normal German citizen) with the recreation of a language destroyed by the demonic uses it had been put to by you know who.

EH: Do you have any advice for a young person who wants to become a famous poet?

FW: Are there any famous poets? Sounds like an oxymoron. I like what Mark Strand said, it’s like being famous in your family. But I am not one to be handing out advice. If I had had the slightest idea of what I was in for, I don’t know if I could have gone forward with all this. Well, probably I would have. I would say that the one and only reward of writing is the experience of writing—if you take it seriously, technically and spiritually—the experience, that secret glory, itself. That’s all there is, let’s face it.

Pingback: - E-Verse Radio