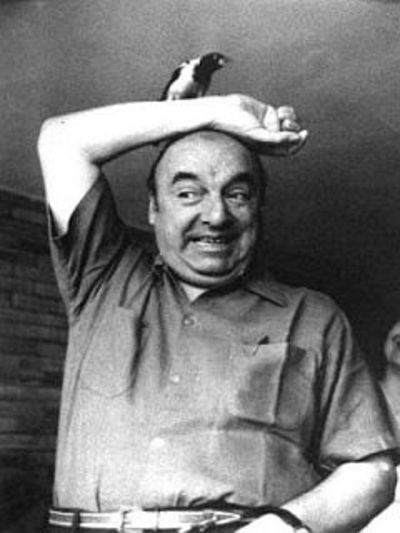

We have all heard the story of an aged Pablo Neruda at a poetry reading, turning down a request to perform a poem from the earlier days of his career, citing a failing memory. There were plenty of copies of it at hand, but the Chilean poet wouldn’t countenance anything as unprofessional as reading his work. The tale ends with the crowd reciting it to him.

What did Neruda know about poetry, though? The guy filled mere stadiums while we North American poets are able to pack entire phone booths! Hey, if it were about numbers we’d all be reading Thomas Tusser (“Who?”). Compare the hodgepodge constituency of Neruda’s audience to the purity of ours—poets and friends only—and the superiority of the anglophone approach becomes obvious, operating as it does without a significant audience. The logic is unassailable: “Why write for those who don’t read poetry?”

Take another, even more anachronistic, example: that guy from Stratford kept two theatres profitable pandering—literally, by many accounts—to the public. That was dramatic poetry. The broader lesson we can surmise is that we must remove any hint of drama from our writing or delivery, lest we attract the kind of fruit-throwing rabble that he did or, worse, draw parallels to slam or performance poets. Similarly, we must avoid populist genres such as comedy, romance, tragedy, and elegy. The issue here is compatibility; it is vital that our subject matter, form and presentation all be equally devoid of vitality.

Cynics may wonder if a worldwide boycott on English language poetry would go unnoticed. (“You mean there isn’t one?”). These people just don’t understand that poetry is meant to be an intimate experience. Lowering the number of unfamiliar faces at readings eliminates the need for crowd control. It reduces stage-fright. It strengthens our case for financial aid as a “nonviable” art form.

Creating a friendly, collegiate atmosphere requires everyone’s participation. For starters, when conferences mention those invited as readers, they really do mean readers. Don’t be confused by the more inclusive term, “presenters.” Those inflicting poetry on attendees will be reading it. Reciting one’s work would be a faux pas; performing it would be downright gauche. Indeed, the latter might be regarded as the height of arrogance—suggesting, at the very least, that these particular words are actually worth remembering. In addition, not having a script might lead to making eye contact with the audience, which could be viewed as peculiar. Invasive. Voyeuristic. Poetry readings are supposed to be private. Even peeking at those who drop in for a nap would seem rude.

Do not be distracted by the fact that our language has a word for reading forgettable text alone or to others, that word being “prose.” Do not assume that attendees are clapping for the reader; those still awake are entitled to express their relief and applaud their own endurance. Above all, do not break stereotype. You were invited to speak because your body of work exhibits traits in common with other presenters; this is hardly the time to “make it new.” Ignore Ezra Pound. Ralph Waldo Emerson, too. Consistency may be the “hobgoblin of little minds” but it’s the hobgoblin who brought you to this gathering.

Finally, readers must understand that, this being the Computer Age, all readings must be in the same robotic voice, absent changes in inflection, tone, or pace. If done perfectly, everyone in the audience—asleep or enthralled—will agree that the performance was mesmerizing.

lol, nice, too many one-liners to keep track.. great way to end the week!