Thomas Hardy’s poem “The Last Signal” is one of his finest elegies. That is already saying a good deal, since a great many of his poems could be defined as elegiac in tone, if not actually in strict form. This clearly is the case with almost all of the poems written about his first wife, whose qualities he seems only to have fully appreciated after her death; as Hugh Haughton has put it, Hardy is pre-eminently the poet of lateness, if not “too-lateness”, and so perhaps it comes as no surprise that so many of his finest poems are written about “the late…”

But having said that, it is worth noting that Hardy did not write many formal elegies in commemoration of people other than those in his close family circle (which included his dogs and cats); there are only a handful of elegies written in honor of other writers, for example (George Meredith, Swinburne, Leslie Stephens), and few of them count among his most memorable work. “The Last Signal”, however, written to commemorate his life-long friend, the writer William Barnes, is one of his most moving poems; indeed, Samuel Hynes wrote: “Nowhere does he show such close emotional bonds to another person, except in the sequence of elegies to his first wife, the ‘Poems of 1912-13”. It is clearly Hardy’s intention to make it clear just how much he owed to the older writer, and he does this in a number of remarkable ways, not least of which is the deliberate employment of various poetical devices closely associated with Barnes’s poetry. In doing so Hardy is not simply paying subtle literary homage to an influential teacher; he is indicating how Barnes helped to shape his whole approach to poetry—and, indeed, to the English language.

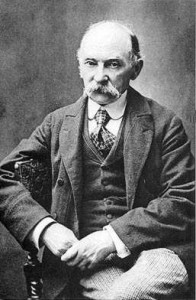

It is hard to exaggerate how important Barnes was in Hardy’s development. Samuel Hynes goes as far as to say: “We can, I think, make two valid statements about Barnes’s influence on Hardy: he is the only poet, with the obvious exception of Shakespeare, whose influence is demonstrable”. The friendship between the two writers began in 1856, when Hardy, at the age of sixteen, worked next door to the village-school that Barnes ran in Dorchester, and continued until Barnes’s death thirty years later. Hardy reviewed his Poems of Rural Life in the Dorset Dialect (1879), wrote his obituary for The Athenaeum and edited and wrote the preface to his Selected Poems.

Barnes was an extraordinary figure, perhaps most efficaciously described by Philip Larkin as “a kind of successful Jude Fawley”. Like Jude (and, of course, like Hardy), he was of humble origins and to a great extent self-educated. His scholarly work included a Philological Grammar, for the compilation of which he drew upon sixty languages; he wrote his daily diary in Italian, read some Persian every week and employed Welsh metrical devices long before Hopkins ever did. His poetry is generally recognized as minor but has had many powerful champions, ranging from Hopkins to W.H. Auden, Geoffrey Grigson and Tom Paulin.

Tom Paulin, in particular, draws attention to Barnes’s insistence on the Anglo-Saxon roots of English and his determination to move away from Latinate vocabulary. To a certain extent Barnes was reviving an argument that had held sway in the 16th and 17th centuries, when such scholars as Richard Mulcaster and John Cheke had rebelled against the so-called “ink-horn terms” being introduced into the language by lovers of the classics. In his book An Outline of English Speech-Craft (1878), Barnes proposed a series of new Saxon compounds (such as “speech-craft” in place of “grammar”). Despite the antiquarian roots of this controversy, the language with which Barnes made his proposals can sound at times extraordinarily prescient of certain 20th-century trends:

This little book was not written to win prize or praise; but it is put forth as one small trial, weak though it may be, towards the upholding of our own strong old Anglo-Saxon speech, and the ready teaching of it to purely English minds, by their own tongue.

Speech was shapen of the breath-sounds of speakers for the ears of hearers, and not from speech-tokens (letters) in books, for men’s eyes…

It is not too far-fetched to hear an anticipation of Robert Frost’s theory of “sentence-sounds”, which were “always there—living in the cave of the mouth […] real cave things: they were before words were”.

Barnes introduces a number of striking compound-words in both his scholarly work and his poetry, even though few of them ever actually caught on in general parlance. In addition to “speechcraft” for grammar, we find “starlore” for astronomy, “welkinfire” for meteor, “nipperlings” for forceps, “free-breathings” for vowels and “breath-pennings” for consonants. It is not unreasonable to imagine an influence on Hardy’s poetry here; to confine ourselves to some of his best-known poems, we can find such memorable compounds as “blast-beruffled”, “red-veined rocks”, “swan-necked one”, “her yew-arched bed”, “air-blue gown”, “dewfall-hawk” and “wind-warped upland thorn”—not to mention such simple but effective coinages as “unhope”.

When Hardy pays tribute to the aural effects of Barnes’s poetry in his Preface to the Selected Poems, he does so in language that seems deliberately to gesture towards Barnes’s own lexical choices:

His ingenious internal rhymes, his subtle juxtaposition of kindred lippings and vowel-sounds, show a fastidiousness in word-selection that is surprising in verse which professes to represent the habitual modes of language among the western peasantry.

It is typical of Hardy that such a striking Saxon coinage as “kindred lippings” is subtly juxtaposed with the Latinate phrasing of “subtle juxtaposition”.

Samuel Hynes has analyzed well the relationship between the two writers. Naturally enough he points out the many differences, beginning with the statement that “Barnes was a provincial, Hardy was not” and concluding with Hardy’s own description of Barnes’s rustics, who “are, as a rule, happy people, and very seldom feel the sting of the rest of modern mankind—the disproportion between the desire for serenity and the power of obtaining it”. Clearly no-one is likely to mistake a poem by Barnes for one by Hardy. However, Hynes points out that Hardy did learn a great deal from the elder poet. Firstly, he found in Barnes’s poetry “a dramatic form, a form particularly suited to [his] abilities and needs”. And secondly, and no less importantly, Barnes “introduced his young disciples to forms outside the main stream of English poetry which Hardy, with his limited education, would probably not have discovered for himself.” When we consider the distinctive nature of Hardy’s poetry, we must acknowledge that these are not minor aspects. In his elegy for Barnes, Hardy succeeds in paying tribute to these qualities of the elder poet, while creating a poem that is fully Hardyesque in form and spirit.

The poem is based on an actual incident. In The Early Life, Florence/Thomas Hardy states that “Hardy’s walk across the fields to attend the poet’s funeral was marked by the singular incident to which he alludes in the poem entitled ‘The Last Signal’”. And in his exhaustive commentary on Hardy’s poetry, J.O. Bailey quotes from the report of the funeral given in the Dorset County Chronicle of October 14, 1886, to assure us that the coffin was “of polished elm with brass mountings”, and that therefore it was perfectly plausible that the sun would have been been reflected from it as it turned into the road. (To my knowledge no Hardy scholar has yet checked the meteorological records to ascertain whether the sun was shining that day.)

The tiny incident must have already struck Hardy as a very suitable basis for a tribute to Barnes, who had a great fondness for images of striking effects of lighting and colour. Here are some characteristic lines from his most famous poem, “My Orcha’d in Linden Lea”:

An’ brown-leav’d fruit’s a turnen red

In cloudless zunsheen, over head…

Indeed, “zunsheen” is one of Barnes’s favourite words; “gleam” and “beam” are frequent rhymes in his poetry. And Grigson cites as a typical image that of “snow-white linen” against a wintry sky.[1]

Hardy therefore pays tribute to this vein in Barnes’s poetry but makes it very definitely his own; in his poem the gleam of sunshine is reflected off a coffin. In this manner it becomes one of his own memorable lighting-effects. It is rather like passing from a Bellini painting of a Madonna and Child to one by Caravaggio or Rembrandt (one of his favorite painters).[2] Hardy does make something personal and even heartwarming from the image, but it comes amid his own remarkable chiaroscuro imagery.

The poem begins with a typical lone Hardy figure, travelling on an uphill road (see the openings of Under the Greenwood Tree, Return of the Native, The Woodlanders, Tess of the D’Urbervilles…). The destination, of course, is “a spot yew-boughed”, which already suggests a graveyard as the final destination.[3]The journey is being undertaken at a time when the light is changing, and the narrator describes the contrast between the western and eastern sky, ending the stanza with the line “And dark was the east with cloud”. This provides the setting for the “event” of the poem. The event in itself—the flash of light from the coffin—is brief and seemingly unimportant, but undeniably striking.

The second stanza provides further details of the setting, pinpointing the geographical source of the flash: “where the light was least, and a gate stood wide.” The essential ingredients of the poem—the flash of light, the gate and (perhaps) the road—are stark and simple; it is the atmospheric setting that gives these elements meaning and resonance, and of course the speaker’s reception of these elements. Much of the power of the poem lies in the way the narrator shapes the story; as so often in Hardy’s poetry, what we sense is the novelist behind the poet—or, perhaps one could say, the novel behind the poem. Even if the poem contains no dramatic dialogue, we are clearly being presented with a scene of great dramatic effect (in stanza 3, it is actually described as “the livid east scene”); we are reminded of the bonfires on Egdon Heath “embrowned at twilight” or the stark figures of Bathsheba and Gabriel bringing in the harvest against the stormy sky.

It is characteristic of Hardy both in his poetry and his fiction to give us enigmatic glimpses of events seen from odd angles or from a distance; sometimes we have the sense of an almost voyeuristic narrator seeing something not intended for his eyes, and then brooding and creating, if not squeezing, a meaning from it. A group of ironic poems from 1911 is tellingly entitled “Satires of Circumstance in Fifteen Glimpses”. The glimpse is often all that is allowed—but it is usually enough. In “The Last Signal” the narrator turns the momentary flash into a specific message for himself; one might say that a meaning is imposed on the event by the narrator, rather in the fashion of the bird in Robert Frost’s poem “The Woodpile”, “one who takes / Everything said as personal to himself”.

In the last stanza the image of the journey is taken up again; it is now explicitly a “last journey”. In the penultimate line Hardy includes a tribute to his friend’s Saxon compounds, with the coinage “his grave-way”—which, of course, is what all our ways are. The poem concludes with the image of the “wave of his hand”, the signal that sanctions the end of the journey and the “last farewell”. (The image connects the poem interestingly with another elegy in the same volume, “Logs on the Hearth”, in which the poet, observing a log on the fire from a tree that he and his sister used to climb as children, recalls his sister “Just as she was, her foot near mine on the bending limb, / Laughing, her young brown hand awave.”)

The poem is, of course, Hardy’s own last signal to his friend and incorporates, as already seen, a number of “waves” to his friend. The most notable of these, as critics have pointed out, are to be found in the very form of the poem, which contains at least two Welsh techniques that Barnes had introduced into English poetry. Hynes provides a succinct account of these two techniques:

The internal rhyme scheme (“road-abode” [in stanza 1]) is called in Welsh poetry union; Barnes used it in “Times o’ Year.” There is also in Hardy’s poem the repetitive consonantal pattern called in Welsh cynghanedd; in the third line, for example, the pattern is LLSNSLLNS (compare Barnes’s use of the device in “My orcha’d in Linden Lea”). Hardy’s further use of assonance, or vowel chime, makes this one of his finest poems from a purely technical point of view.

These were all techniques that Barnes not only used in his own poetry but defined in his Philological Grammar, which could be said to be the Book of Forms for his own day, providing examples from the poetry of sixty languages. (Here, for example, is his definition of union: “under-rhyme, or rhyme called union, which is the under-rhyming of the last word or breath-sound in one line, with one in the middle of a following one.”) Hardy does not simply use these devices as a kind of literary “in-joke”; they are an intrinsic part of the poem’s meaning, not only making it one of his most musically fascinating but testifying to the strength and profundity of the bond he felt with the older poet.

There is at least one other element in the poem that can be considered a tribute to Barnes, and it is one that critics do not seem to have picked up on (at least, not to my knowledge). This is the image of the gate, found in line 6 (“Where the light was least, and a gate stood wide”) and in line 14 (“Trudged so many a time from that gate athwart the land!”).

Gates and doorways are potent symbols in Hardy’s works. It has been said that The Return of the Native is essentially a tragedy of an unopened door (and something similar could be said of his first novel Desperate Remedies). There are not many homes in Hardy’s fiction; we do not find the comfortable or intriguing interiors so typical of Dickens’s novels. His characters tend to live in vans, in towers, in huts in the wood or on the road. When they do have houses, they are frightened of losing them, because of expired leases, unpaid rent or even invasion by the French. The inhabitants of houses, in both his novels and his poems, are most typically glimpsed in doorways or leaning out of windows (think of our first view of Fancy in Under the Greenwood Tree, or the “rash bride” in the poem of that name—a poem that seems closely connected with the novel).

Doorways and casements are, of course, well-suited to the narrative-strategy of the glimpse. His characters are often caught in revealing poses or situations through windows and doorways, either by other characters (“Seen by the Waits”; “In Church”; “Outside the Window”), or by the moon (“Shut Out That Moon”; “The Moon Looks In”), or by the creatures of the place, as in “The Fallow Deer at the Lonely House”, which presents what one might almost call the archetypal Hardy situation: “One without looks in to-night / Through the curtain-chink…”. Homes are never inviolable sanctuaries in Hardy’s fiction and poetry. Perhaps the culmination of this imagery comes in the final chapter of Tess of the D’Urbevilles, where Tess’s last home consists of nothing but open doorways: ancient stone ones, providing no protection, safety or comfort.

Thus the image of the gate can be seen in its way as a typically Hardyesque image; we might be reminded that his famous poem contemplating his own death uses the image of the “postern” (“When the Present has latched its postern behind my tremulous stay…”, in “Afterwards”, the concluding poem of Moments of Vision). But the image in “The Last Signal” is perhaps also a tribute to the last poem William Barnes ever wrote, dictated to his daughter on his death-bed. Entitled “The Geäte A-Vallèn To”, it is one of his finest poems, relying for its effect on the symbolic power of the image indicated in the title, which is used with a gentle elegiac touch. Each of its five stanzas concludes with the words of the title; the final stanza reads:

An’ oft do come a saddened hour

When there must goo away

One well-beloved to our heart’s core,

Vor long, perhaps vor aye:

An’ oh! it is a touchen thing

The loven heart must rue,

To hear behind his last farewell

The geäte a-vallèn to.

It seems likely that Hardy, writing a poem in which he makes his “last farewell” to his old friend, would include a “wave” to his friend’s poignant valedictory poem. Hardy’s elegy, which is as much a celebration of his great mentor as it is a poem of mourning, interestingly reverses the image of the gate, as found in Barnes’s poem. The gate in “The Last Signal” “stood wide”: this indicates on the one hand that Barnes’s coffin has passed through it for the last time but it also perhaps subliminally points to the way Barnes’s life and poetry opened the way for his pupil. It is certainly in contrast with the image of the “postern” in the poem that we might almost consider Hardy’s elegy for himself, where we have the suggestion of the speaker being irrevocably thrust out from the back-door of life.

In conclusion, of all Hardy’s numerous poems that deal with death, “The Last Signal” is perhaps the least depressing. The celebratory aspect – which relies to a great extent on the numerous and varied ways Hardy succeeds in paying tribute to his old friend – gives the poem something of the consolatory force one might customarily associate with religious literature. The poet Patricia Beer, in an essay aptly entitled “A Poet of Farewell”, said of Hardy’s elegies for his wife that they possessed a quality she could only define as “the light of loss, the illumination that sadness might bring to a man of Hardy’s temperament, who consciously believed in the value of suffering.” “The Last Signal” is much less a poem of suffering than most of Hardy’s works, but Beer’s description nonetheless seems peculiarly apposite. Indeed, one could say that the last signal Hardy describes in this poem—the flash of light from the departing coffin—is a literal embodiment of that “light of loss” that she claims characterizes his best works.

[1] A few more examples: “When wintry weather’s all a-done, / An’ brooks do sparkle in the zun” (“The Spring”); “Wi’ yollow buttons all o’ brass, / That glitter’d in the zun lik’ glass” (“Easter Zunday”); “As I went eastward, while the zun did zet, / His yollow light on bough by bough did sheen (“Lowshot Light”). This last poem seems particularly close in its imagery to Hardy’s tribute, listing the various objects the “lowshot light” of the sun catches: the tree-boughs, the cows, the plough and finally “One lovely feäce”.

[2] See this description from Chapter 50 of Far from the Madding Crowd: “The strange luminous semi-opacities of fine autumn afternoons and eves intensified into Rembrandt effects the few yellow sunbeams which came through holes and divisions in the canvas, and spirted like jets of gold-dust across the dusky blue atmosphere of haze pervading the tent, until they alighted on inner surfaces of cloth opposite, and shone like little lamps suspended there.”

[3] This footnote is probably the best place to mention that I have followed in Hardy’s footsteps and discovered that there are now no yew trees at the top on the hill between Max Gate and Winterborne Came.

This is all delightful and lucid. I would have found it helpful to have the Hardy poem in front of me, rather than having to go find it on the web or on my bookshelf–I find it hard these days to interrupt the process of reading an essay in order to look up something, however essential. Thank you, however, for your scholarship and your appreciation of both Barnes and Hardy.