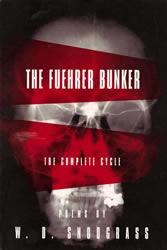

Interviewer’s note: William DeWitt Snodgrass is commonly credited with inaugurating the “confessional” era in American poetry in 1959 with his first collection, Heart’s Needle. It went on to win the Pulitzer Prize, and there is evidence that it influenced Robert Lowell’s own pioneering collection Life Studies. Snodgrass went on to write successfully in a great variety of styles on a wide range of themes—oscillating easily between bawdy lyrics and apocalyptic narratives (incredibly, both appear side by side in his classic, and controversial, epic cycle the Führer Bunker). He has also translated songs and poems out of several languages into English and worked as an editor and anthologist. While he was traveling near Philadelphia, Mr. Snodgrass set aside some time for me to visit his hotel room where we recorded a conversation about his influences, his associations with American masters John Berryman, Robert Lowell, and Randall Jarrell, and the dust that kicked up in the 1970s around the Führer Bunker. What appears below is a transcription of that taped recording.

Interviewer’s note: William DeWitt Snodgrass is commonly credited with inaugurating the “confessional” era in American poetry in 1959 with his first collection, Heart’s Needle. It went on to win the Pulitzer Prize, and there is evidence that it influenced Robert Lowell’s own pioneering collection Life Studies. Snodgrass went on to write successfully in a great variety of styles on a wide range of themes—oscillating easily between bawdy lyrics and apocalyptic narratives (incredibly, both appear side by side in his classic, and controversial, epic cycle the Führer Bunker). He has also translated songs and poems out of several languages into English and worked as an editor and anthologist. While he was traveling near Philadelphia, Mr. Snodgrass set aside some time for me to visit his hotel room where we recorded a conversation about his influences, his associations with American masters John Berryman, Robert Lowell, and Randall Jarrell, and the dust that kicked up in the 1970s around the Führer Bunker. What appears below is a transcription of that taped recording.

Ernest Hilbert: I’ve heard rumors that you were raised as a Quaker. Is that true?

W.D. Snodgrass: No. My parents were United Presbyterians. I was a Quaker for about six months or so when I was in school in Iowa. They had a wonderful Quaker meeting there, and I never found one after that that was quite so splendid. I was born in Beaver Falls, Pennsylvania, but my family lived in Wilkinsburg [PA]. They came back to Beaver Falls for my birth because my father’s father, who was a physician, was in the hospital there. So they took me down there for the birth and then took me immediately back to Wilkinsburg. But later we moved to Beaver Falls and I grew up there.

EH: You served in the navy.

WDS: I was a yeoman, a typist. I was on Saipan for two years.

EH: After leaving the navy, you transferred from Geneva College to the University of Iowa. What inspired that decision?

WDS: Iowa had the only creative writing department in the country at the time. It was very hard to get into. Fortunately, my mother knew a lady on the board of trustees [laughs].

EH: You studied at Iowa at a heady time. John Berryman, Randall Jarrell, and Robert Lowell taught there.

WDS: When I first came, none of them were there. Lowell came several years later. At first, I was not in the creative writing department. I was in the theater department. I wanted to write plays, but my plays were lousy. The only way they could’ve gotten worse was for me to do what my teacher was telling me. She was totally incompetent. She had been a girlfriend of Tennessee Williams, insofar as he could have a girlfriend. She kept him in food and drink.

EH: What are your memories of Berryman?

WDS: The head of the creative writing department was Paul Engle, but he was often out recruiting students. One semester when he was gone, John Berryman took his place, but Berryman soon got into trouble—he got drunk and wrecked his room, and the police threw him out of town.

EH: Jarrell?

WDS: As for Randall Jarrell, he came to Colorado, to Boulder, and taught a creative writing class for three weeks. I got to attend because there was a lady historian who had delivered a lecture at Iowa and had given her payment back and said “give this to the students as a fellowship.” I got one of those.

EH: And Lowell?

WDS: I took Robert Lowell’s course a number of times. I have to say his was the biggest mind I’ve ever encountered. It was fantastic. A friend of mine said, “when he does your poem in class, it’s like having a gigantic octopus sit on it, and it sends out one arm and gets religion, and sends out another and gets mythology, and another comes back with science. You sit there and think: ‘My poor little poem doesn’t need any of those things.’” Then you’d run into him on the street three days later, and he’d come up and put his arm around you and say, “you know I’ve been thinking about your poem, the one with the rather grand language”—and that is not a compliment—“I was all wrong about that. It isn’t about that at all.” He’d have a whole new set of theories about it. It was simply staggering. I was also in a class in which we did The Iliad. He and Gerald Else, who was then the leading classicist in the country, taught it jointly. I was the only one in the class who had taken any Greek. The rest were young poets. The first forty-five minutes of the class, Lowell would throw out the most wonderful, exciting, brilliant ideas about these lines from The Iliad that you’d ever heard, and for the rest of the class Else would tell you what it was really about.

EH: Was Berryman there long enough for you to develop a relationship with him?

WDS: Oh yes. As a matter of fact I remember that in the long cycle of poems that I was first known for, “Heart’s Needle,” about my daughter and thinking I would lose her in that divorce. Lowell didn’t like those poems at all. He said, “Snodgrass, you’ve got a brain. You can’t write this kind of tear-jerking stuff!” Berryman, on the other hand, did like them, and as a matter of fact there is one line in there that he suggested. He said “why don’t you do this instead,” and I did. Two years later, I mentioned to Gertrude Buckman, the widow of Delmore Schwartz, that no one would print “Heart’s Needle.” She took them and showed them to Lowell, and then he fell in love with them.

WDS: Oh yes. As a matter of fact I remember that in the long cycle of poems that I was first known for, “Heart’s Needle,” about my daughter and thinking I would lose her in that divorce. Lowell didn’t like those poems at all. He said, “Snodgrass, you’ve got a brain. You can’t write this kind of tear-jerking stuff!” Berryman, on the other hand, did like them, and as a matter of fact there is one line in there that he suggested. He said “why don’t you do this instead,” and I did. Two years later, I mentioned to Gertrude Buckman, the widow of Delmore Schwartz, that no one would print “Heart’s Needle.” She took them and showed them to Lowell, and then he fell in love with them.

EH: Did he realize they were the same poems?

WDS: I don’t know. I know that he went to work to get them published. He went to Knopf and they accepted the book. Otherwise, I might never have published those poems. He later said he was taking the poems as a model, and that scared the hell out of me. I thought, “here I am doing something you’re not supposed to do, and he’s going to follow. I’ll be responsible!” It scared me half to death. I worshiped Lowell.

EH: So you had a distinct influence on Lowell’s Life Studies?

WDS: Oh yes, definitely. He wrote me to say so.

EH: You were featured in Hall, Pack, and Simpson’s highly influential anthology New Poets of England and America. I still keep a copy by my bedside. What do you make of Hall’s division of the tweeds and the sandals, for instance? What Lowell called the cooked and the raw? Which one were you?

WDS: I was cooked! But that’s really up to a critic to decide. I did a lot of different things than the other so-called academic poets. Most of the best of the Beats, as far as that goes, came out of the academy. Ginsberg was at Columbia.

EH: Are there similar divisions in American poetry today?

WDS: There are so many poets today; I simply can’t keep up with them.

EH: Do you think anyone could?

WDS: Oh, yes, if you didn’t do anything but read books of poetry morning till night every day.

EH: Maybe we should appoint a national poetry reader who could submit a report to congress each year.

WDS: [Laughs]

EH: You won the 1960 Pulitzer Prize for your first book, Heart’s Needle, which was published the previous year. Were you ready for the fame?

WDS: Nobody is ever ready for that kind of change. Shortly after, Norman Mailer wrote about how winning an early prize can ruin a career. So did Tennessee Williams. Suddenly schools that wouldn’t have taken me as a student wanted me to come and give readings. It simply changes everything.

EH: How does fame change the way a poet writes?

WDS: It affects different poets different ways.

EH: How did it affect you?

WDS: A critic could probably tell you better than I can. After that I wrote one more set of poems about somebody in my immediate family, about the death of my younger sister, who, I felt, had been destroyed by our mother. After that, I thought I would have to find other things to write about, other ways to approach it. I didn’t want to go on doing the same sort of thing. I knew I could do that. The only thing worth doing is something you think you maybe aren’t able to. I know I was somewhat influenced by the Beats. They hated me. I was especially influenced by the fact that they always read the poems aloud. So I started doing much more of that. I took voice lessons, both with a speech teacher and singing teachers. I also started doing lots of translations, mostly translations of songs, so I could sing them.

EH: The term “Confessional” was first used by M. L. Rosenthal in a review of Robert Lowell’s Life Studies in The Nation. That article was published in September 1959, the same year that Heart’s Needle appeared. Since then, some have suggested that you were, in fact, the first Confessional poet. What do you say to that claim?

WDS: As I said, Lowell saw my poems, at first didn’t like them, and then later decided he did. He wrote to me and said “I’m taking you as a model.” Just exactly as he, at first, gave me hell for writing poems as personal as that, his teacher, Allen Tate, gave him hell. I was particularly lured by several influences, one of which was going to work with Jarrell who said, “Snodgrass, do you know you are writing the very best second-rate Lowell in the whole country? But there’s only one person writing any first-rate Lowell, and that’s Lowell.” Two other things, both of them musical, also moved me. I had been a musician. If there had been any jobs, I would be playing tympani in a symphony someplace, but there weren’t any. There were only about ten decent orchestras in the country then, and every one of them had a young timpanist except for Philadelphia, who had an old man named Oscar Schwar, and he had a pupil! But two things moved me. One was the kindertotenlieder of Gustav Mahler, songs for the death of children. They very much moved me toward writing about losing my daughter. They were very personal poems. The second thing was that I heard an album by Hugues Cuenod—who, just yesterday I sent a 105th birthday card to—an absolutely wonderful tenor and a marvelous man. He recorded 16th and 17th-century songs from Spain and Italy. When I heard those, I knew right away I had to change. The poems I was writing had everything except that clarity and that passion. His recordings did as much to change the way I wrote as anything else. Cuenod made his debut at the Met when he was 85 years old. Stravinsky rewrote his opera The Rake’s Progress to give Cuenod a part. Still, I must say that Jarrell had a hand in my development as well. He was a tough teacher. He really beat you up. No teacher I know would do the things he did. Especially if he thought you had some promise.

EH: Can you give an example?

WDS: We went out to a little out-door coffee shop, where students sat around with Cokes, and he would read loudly my poems and howl with laughter and slap his thigh and say, “Snodgrass, you wrote that? Listen to this. You wrote that! Wait a second, I’ve gotta read this again!” So all these students would hear me being beat up.

EH: Like a public flogging. He had you in the stocks!

WDS: Yes, but the bastard, he was right. He knew what was sentimental and what was not and what was just in the poem because teachers told you that’s what you put in poems.

EH: How important are formal elements like meter and rhyme to poetry?

WDS: That’s one thing you can do, but you don’t have to. I make up prosodies. Also free verse.

EH: Are there advantages to publishing with a small press sometimes rather than a commercial one?

WDS: Commercial presses can give you much better advertisements and can push the book. It is also much more likely to get attention from major critics.

EH: You first published parts of the Führer Bunker series in 1977 with the subtitle “A Cycle of Poems in Progress.” Why did you decide to publish portions of it before the cycle was completed?

WDS: Because I had gone for a good many years without bringing out any kind of book. I wanted people to know that I was working like hell, and that I hadn’t quit writing or anything like that. Al Poulin, Jr. was willing to do this book with BOA Editions. He heard the poems when I read them in Brockport, NY, and was very much taken by them. I thought, “okay, it’s big enough to be a book now.”

EH: Would you describe Führer Bunker as a series of dramatic monologues?

WDS: Yes.

EH: What sort of reaction did the book inspire among critics and readers at the time?

WDS: Horror. It made me an instant pariah. The important magazines dropped me. People would come to my readings just to turn their backs on me at the reception. I was kept out of anthologies and critical discussions.

EH: What were they afraid of?

WDS: I gave a reading one night for American Poetry Review, for Steve Berg, who had been a friend and often been a supporter. I read all poems from that cycle. When it was over, a man got up and said, “How dare you glorify these monsters!” I said worse things about the Nazis than any historian, and most of the audience agreed. The man sat down and shut up. The next day I got a letter from him with the same accusations but instead saying “you’ve humanized them.” As Joe [X.J.] Kennedy has said, that’s exactly the point. They are human. And we all have histories that show we’re all capable of such atrocities.

EH: Did you get support from other poets at the time?

WDS: Well, Don Hall. [His wife, Kathleen Snodgrass, who was in the room at the time, interjects here] KS: Robert Lowell said very nice things. WDS: Yes he did. He wrote me that he had tried to write about Hitler and wasn’t able to. He also wrote “I hope you know you are hated in many circles here, in New York, but I am on your side on this.” Donald Hall recently said, “That’s a wonderful poem.” It’s all changing now. Younger poets often come up to me and say, “The Bunker poems are the ones I like best.” If I may brag, Daniel Ellsberg twice said it’s a masterpiece. The original attitude is changing, but back then I gave a reading in New York from the Bunker cycle at the Manhattan Theater Club, and only twenty people came. Fifteen were on the staff. So five people came, from all New York . . . .

EH: You adapted the Führer Bunker for the stage, and it was performed at the American Place Theatre in New York in 1981. Were you happy with the result?

WDS: Yes and no. It was directed by Carl Weber, who had worked for ten years with Bertolt Brecht. It was a great pleasure to watch the way he worked with people on this. Wynn Handman—to whom I’m grateful—suggested I do it, and who else would have had the nerve to put it on? We mounted it three times. The first time, I was satisfied with it. But the composer said, “I don’t think we’ve done any service to the text with this.” He was a well-known Broadway composer, Richard Peaslee. They brought it back and did a much more experimental thing. One actor would take on more than one role at different times. You had musicians right up front on the stage. The percussionist in particular was of great importance. Speakers were hidden around in different parts of the theater, so voices would come out behind the audience. I thought “This treats it as what it is. It is not a play. It is a cantata for speakers.” I had written choruses for it, and this treated it like a musical piece. It is certainly not a play. You can’t have a play with Hitler in it, because no one can openly show conflict with him. Though the characters, the top Nazis, all want to undercut him and replace him, they could never say so. It’s all inside the individual speaker. This approach allowed that to come out. For the third and final version, they went back to something closer to the earlier version, more like a stage set for a play. That was partly because they felt the other approach involved too much amplification of voices. The audience can’t take too much of that.

WDS: Yes and no. It was directed by Carl Weber, who had worked for ten years with Bertolt Brecht. It was a great pleasure to watch the way he worked with people on this. Wynn Handman—to whom I’m grateful—suggested I do it, and who else would have had the nerve to put it on? We mounted it three times. The first time, I was satisfied with it. But the composer said, “I don’t think we’ve done any service to the text with this.” He was a well-known Broadway composer, Richard Peaslee. They brought it back and did a much more experimental thing. One actor would take on more than one role at different times. You had musicians right up front on the stage. The percussionist in particular was of great importance. Speakers were hidden around in different parts of the theater, so voices would come out behind the audience. I thought “This treats it as what it is. It is not a play. It is a cantata for speakers.” I had written choruses for it, and this treated it like a musical piece. It is certainly not a play. You can’t have a play with Hitler in it, because no one can openly show conflict with him. Though the characters, the top Nazis, all want to undercut him and replace him, they could never say so. It’s all inside the individual speaker. This approach allowed that to come out. For the third and final version, they went back to something closer to the earlier version, more like a stage set for a play. That was partly because they felt the other approach involved too much amplification of voices. The audience can’t take too much of that.

EH: Are you still working on the series?

WDS: I am. I spent thirty-five years on it, and hadn’t expected to do any more. But Joachim Fest, the historian who was born in Berlin and grew up there, brought out a book just before he died called Albert Speer: The Final Verdict. He reveals that since Speer died a number of documents have come to light that show him to have been much more involved in the dirty work.

EH: He was not the “good Nazi.”

WDS: Right. Dan van der Vat’s book on Speer called The Good Nazi came out just before that. I’m not used to talking to interviewers who are as well read as you are. I had interviewed Speer myself at his house in Heidelberg, right up above the castle. He was very gentlemanly, and I like him. Gitta Sereny has a book about him called Albert Speer: His Battle with The Truth. She occasionally lived with Speer and his wife. Although, like myself, she didn’t believe he was as innocent as he claimed, she liked him. I felt much like that. You couldn’t be that high in the Nazi hierarchy and not know what was happening. Proof now has come out that he was indeed involved in a lot of things, including the emptying of the so-called “Jew Flats” in Berlin. Something like 35,000 people were thrown out of their houses to build the new big Germania.

EH: Based on Rome.

WDS: Exactly. There were other things like that. Of course he knew. He had seen groups of people standing on the street with their luggage being taken places.

EH: Will you be adding portions to the cycle devoted to Speer?

WDS: I’m rewriting all of his speeches. There are six. I just finished those, and I’m writing one last speech after he has said good-bye to Hitler. The last thing he did there was to go in and say goodbye. They flew in and landed on Unter der Linden, and he went and confessed to Hitler that he had not obeyed the command to destroy everything. He came out and the next day after that he went to Hohenlychen, which was a clinic run by Himmler, where he had been a patient. He believed Himmler had tried to kill him while he was there. He went and talked to Himmler, and Himmler was sure that he would be needed by Eisenhower to keep peace after the war.

EH: Or to help fight the Bolsheviks.

WDS: Right. Himmler was really such an idiot. I’ve written a speech for Speer after Himmler has driven away and Speer is making his post-war plans. The essence of it is that he knows so much about what the British did wrong in their attacks, ways they could have ended the war sooner. Speer knows that if he can give this kind of information to the east or the west, he can perhaps save his life.

EH: Trying to save his own neck in the eleventh hour.

WDS: There are rumors that he did. He had a couple of sessions with important British and American officials, and some think—and I rather tend to agree—that’s how he got twenty years instead of hanging.

EH: For trading war secrets.

WDS: Already, the Russians and the west were at each other’s throats and dividing up the German scientists. So it’s quite possible it happened. Also, he planned to plead guilty, which would suggest to them that even though he hadn’t always done right he shared the west’s moral convictions generally.

EH: Will we see another edition of the Fuhrer Bunker?

WDS: No, I imagine these new poems will not be seen until after my death. I hope there will be a collected Snodgrass, and I will inform my editor that I want him to replace those sections with the new ones.

EH: Now that we’ve covered tragedy so thoroughly, let me ask you what role humor plays in poetry.

WDS: I don’t think in big terms like that, but it’s clear that as traditional meter and an elevated tone that suggest some connection with high spiritual matters has declined, humor and comedy have increased.

EH: Years ago, when editing the Oxford Quarterly, I was privileged to publish “Toma Alimos,” a Romanian Folk ballad you translated with Nicolae Babutz. I now realize that by that time [1995] you were interested primarily in translating songs and ballads. Why did you decide to switch from the translation of lyric poetry to songs?

WDS: Because I do have a musical background. I played the violin very badly, piano quite badly, but then I became a pretty good timpanist. I also did some choral conducting. I even got to conduct a rehearsal of the Beethoven Third. You feel like a god doing that. After the war, it was clear that I had to get out of music. Still, music was always of great importance to me. There were an awful lot of people translating poets from different languages and doing quite brilliant jobs of it. But nobody seemed to be translating songs. Besides which, I wanted to sing them. I was playing the guitar and the lute.

EH: What relation does a modern lyric poem, like “April Inventory,” for instance, bear to a traditional folk ballad like “Toma Alimos”? Are they different things or do they share a lineage?

WDS: “Toma Alimos” comes out of a peasant culture. Something like “April Inventory,” which is in traditional prosody, is part of a courtly tradition, probably more from the troubadour tradition. Some of the troubadours were peasants, but they were singing for the court.

EH: So would a song from the peasant tradition be more “earthy,” or bawdy, perhaps less refined?

WDS: Some of the troubadour songs are pretty dirty. I’ve never published in this country all the troubadour songs I’ve translated. I’ve done 22 of them. One of them was published only in France. It was by Guilhem de Peitieus, the first troubadour, and it is called “Leis de Con” [the “law of cunt”]. There is no other way to translate that. They wouldn’t have known the word vagina or any derivation of it. That was the only word they had. It didn’t have any of the ugly connotations then that is has today.

EH: You translate with the help of a collaborator who is familiar with the language of origin. You once remarked that it is “a lot easier to translate poems if you don’t know the original.” Why is that? You mentioned Lowell with The Iliad.

WDS: [laughs] Well, he did read Ancient Greek. Ancient Greek is the only language I ever learned. The only translation I’ve ever done from the Greek was about 20 lines of the Iliad into 30 lines of English alliterative meter.

EH: So you translated it from the dactylic hexameter into accentual English meter?

WDS: Yes, with alliteration joining the half lines. But that was so hard. It took many months. And I thought, “Who the hell’s going to publish this anyway.” But I’m kind of impressed by it. It sounds like something that could be recited in a mead hall.

EH: Your wife Kathleen also translates poetry. Do you collaborate with her?

WDS: We were with a group of people in Germany called Societé Imaginaire. The meetings were just such awful horseshit. But there was a Polish poet named Leszek Szaruga, which means “Louis Starkweather.” He was very unlike the others. He had been with Solidarność [Solidarity] for many years and had to leave Poland for Germany. We got to talking to him about Zbigniew Herbert, whom we both greatly admired. We were so taken by his commitment to Herbert that we thought, “let’s try some of his poems.” He didn’t have English. We didn’t have Polish. There was a Hungarian there who had both English and Polish. So we mediated our discussion through those languages. The four of us would get together and work out translations of Szaruga. Since then Kathleen and I have been going regularly to Mexico, for 25 years. We go to San Miguel De Allende. Kathleen had both Spanish and French in school. She’s been steadily picking up more Spanish down there. She’s been translating Luis Miguel Aguilar. He was absolutely delighted. He edits a very fine magazine down there. Then she’s worked with five other Mexican poets. She’s the only one I know who has translated a villanelle and as a villanelle and sestina as a sestina, “the Narrow Bed” and “The Broad Bed.” I don’t know Spanish, but I’m damn sure these are as good as the Spanish.

EH: In your book De/Compositions: 101 Good Poems Gone Bad you take apart poems by Stevens, Auden, and even Shakespeare, to reveal how important every facet of a particular poem is. How does this relate to the art of translation?

WDS: This gets back to something I said earlier, that you might be better off not knowing the original language. Because that language is going to be full of things that can only fully be grasped by someone who took in that language with their mother’s milk. The most obvious things are puns. When I work on poems, very often the person I’m working with indicates that something has a double meaning. I hunt for something in English that will do the same thing. Once or twice I’ve found it. But only once or twice. Most of the time, that, and certainly deeper richnesses are not going to be available in English. So I find myself often picking up suggestions or tones of voice that weren’t in the original. Looking for puns, looking for richnesses and so forth. I’m interested in making an interesting poem in English. The dictionary sense of a poem from another language is almost never of much interest. Mrs. M.D. Herder Norton’s versions of Rainer Maria Rilke make you wonder, “Why did anyone ever think this was a poem?” It just doesn’t have that richness, that depth.

WDS: This gets back to something I said earlier, that you might be better off not knowing the original language. Because that language is going to be full of things that can only fully be grasped by someone who took in that language with their mother’s milk. The most obvious things are puns. When I work on poems, very often the person I’m working with indicates that something has a double meaning. I hunt for something in English that will do the same thing. Once or twice I’ve found it. But only once or twice. Most of the time, that, and certainly deeper richnesses are not going to be available in English. So I find myself often picking up suggestions or tones of voice that weren’t in the original. Looking for puns, looking for richnesses and so forth. I’m interested in making an interesting poem in English. The dictionary sense of a poem from another language is almost never of much interest. Mrs. M.D. Herder Norton’s versions of Rainer Maria Rilke make you wonder, “Why did anyone ever think this was a poem?” It just doesn’t have that richness, that depth.

EH: You have written under the pseudonym S.S. Gardons. What have you published under that name?

WDS: Oh dear! The poems about my sister’s death and my feeling that my mother was the cause of it. Not that she meant to be, not that she could help it, not that she could do other than she did. But if I had published those under my own name, she would have gone into the department store and seen a book by me and bought it. It would not only damage her to be thought at fault, but it would have made it worse. Until my mother and father had died I published those under that name. I have three or four other pseudonyms.

EH: Can you tell me what they are?

WDS: Mostly they are versions of Snodgrass spelled sideways. Dan S. Gross. Will McConnell. McConnell is a family name. I did translations from Kozma Prutkov.

EH: What do you publish under the pseudonyms?

WDS: Well, I’ve been married four times. KS [his wife]: Now you tell me!

EH: The truth comes to light!

WDS: [laughs]

EH: Do you have any advice for young poets today?

WDS: If you can be happy doing anything else, do it. George P. Elliott once told me that. This is what he always told people. Everything pays better. Everything is more honestly rewarded. But if you’ve got to do it, then you’re a life-termer. I’ve had a lot to do with pacifist organizations. In one of their publications there is a story about a young pacifist who is thrown in prison. He is in on the main floor with all the new guys, and he’s cracking up. Some of the prisoners go to the warden and ask him to do something. They put the new guy up on the top floor with the life-termers, because they had nothing to win. They didn’t have to put anybody down. They were just there. And that’s how it was going to be, and they had to get along. In a few days he settled back down again and he was all right.

EH: So being a life-termer as a poet, the competition falls to the wayside, the strange struggles, and you resign yourself to being a poet.

WDS: That’s right.

Pingback: Ernest Hilbert | INTERVIEWS