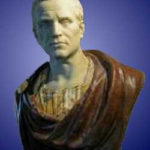

It is not until the reign of that frustrated artist and unsurpassed egotist, Nero, that we again recognize the true dandy, so insolent in repose, embodied in the fragmentary figure of Gaius Petronius (Arbiter). Nero was particularly sensitive to the opinions of artists. Just as Seneca had exercised a benevolent influence on the young emperor, so it was Petronius who drove Nero in his later years into a life of such extraordinary indulgence that it has no earthly parallel. What possessed that mad emperor to bequeath the title elegantiae arbiter (the “director of imperial pleasures” or “judge of elegance”) to a man of his court? And how did Petronius live in such a way as to attract the admiration of the world’s supreme ruler—a man whose name is still a by-word for extravagant excess and outrageous cruelty? (A man, lest we forget, who never travelled with less than thousand wagons in his train, and a thousand servants to mind his wardrobe, with the mules shod in silver and drivers dressed in Tyrian purple and gold. A man who nearly exhausted the imperial treasury in building a pleasure palace for himself so vast that it covered a third of the entire city of Rome! A man so gaudy that the bronze statue of himself at the palace’s entrance required 24 elephants to drag away!) It is Tacitus, in his Annals, who remarks of the Arbiter that:

It is not until the reign of that frustrated artist and unsurpassed egotist, Nero, that we again recognize the true dandy, so insolent in repose, embodied in the fragmentary figure of Gaius Petronius (Arbiter). Nero was particularly sensitive to the opinions of artists. Just as Seneca had exercised a benevolent influence on the young emperor, so it was Petronius who drove Nero in his later years into a life of such extraordinary indulgence that it has no earthly parallel. What possessed that mad emperor to bequeath the title elegantiae arbiter (the “director of imperial pleasures” or “judge of elegance”) to a man of his court? And how did Petronius live in such a way as to attract the admiration of the world’s supreme ruler—a man whose name is still a by-word for extravagant excess and outrageous cruelty? (A man, lest we forget, who never travelled with less than thousand wagons in his train, and a thousand servants to mind his wardrobe, with the mules shod in silver and drivers dressed in Tyrian purple and gold. A man who nearly exhausted the imperial treasury in building a pleasure palace for himself so vast that it covered a third of the entire city of Rome! A man so gaudy that the bronze statue of himself at the palace’s entrance required 24 elephants to drag away!) It is Tacitus, in his Annals, who remarks of the Arbiter that:

He spent his days in sleep, his nights in attending to his official duties or in amusement, that by his dissolute life he had become as famous as other men by a life of energy, and that he was regarded as no ordinary profligate, but as an accomplished voluptuary. His reckless freedom of speech, being regarded as frankness, procured him popularity. Yet during his provincial government, and later when he held the office of consul, he had shown vigor and capacity for affairs. Afterwards returning to his life of vicious indulgence, he became one of the chosen circle of Nero’s intimates, and was looked upon as an absolute authority on questions of taste in connection with the science of luxurious living.

Having attracted the jealousy of Tigellinus (the commander of Nero’s imperial guard), Petronius was arrested for treason at Cumae. Disdainful of such trumped-up charges, he preferred suicide to a trial. Tacitus records:

Yet he did not fling away life with precipitate haste, but having made an incision in his veins and then, according to his humor, bound them up, he again opened them, while he conversed with his friends, not in a serious strain or on topics that might win for him the glory of courage. And he listened to them as they repeated, not thoughts on the immortality of the soul or on the theories of philosophers, but light poetry and playful verses. To some of his slaves he gave liberal presents, a flogging to others. He dined, indulged himself in sleep, that death, though forced on him, might have a natural appearance. Even in his will he did not, as did many in their last moments, flatter Nero or Tigellinus or any other of the men in power. On the contrary, he described fully the prince’s shameful excesses, with the names of his male and female companions and their novelties in debauchery, and sent the account under seal to Nero. Then he broke his signet-ring, that it might not be subsequently available for imperiling others.

He died as Seneca had died, and he paid the same price as almost everyone did who was too close to the unstable and paranoid emperor. We have his Satyricon still. Widely considered the first novel of imaginative prose ever written, its portrait of pederasts and gourmands run amok in Imperial Rome is still shocking and influential. (The working title of F. Scott Fitzgerald’s Great Gatsby was Trimalchio in West Egg.) It should hardly surprise us that it was also a great favorite of Oscar Wilde’s, who translated the book and had it published in Paris under the pseudonym Sebastian Melmoth. Its dandyism, alas, is one of grotesque excess and neo-pagan nihilism, and not for the faint of heart. There is precious little in the way of philosophy that can be deduced from the wild immorality of the Satyricon, but many feel that we hear the true voice of Petronius in fragments like: “Nihil est hominum inepta persuasione falsius nec ficta severitate ineptius” (“There is nothing about man more false than his foolish convictions and there is nothing more stupid than hypocrite severity”). As we possess a mere tenth or so of the complete work, we probably should not judge the Arbiter too harshly for our own mystification.

We also have a small number of Latin poems attributed to him. Here is one, translated into English, on a subject that we can imagine was a favorite of his:

Laid on my bed in silence of the night,

I scarce had given my weary eyes to sleep,

When Love the cruel caught me by the hair,And roused me, bidding me his vigil keep.

” O thou my slave, thou of a thousand loves,Canst thou, O hard of heart, lie here alone? ”

Bare-foot, ungirt, I raise me up and go,I seek all roads, and find my road in none.

I hasten on, I stand still in the way,

Ashamed to turn back, and ashamed to stay.

There is no sound of voices, hushed the streets,Not a bird twitters, even the dogs are still.

I, I alone of all men dare not sleep,But follow, Lord of Love, thy imperious will.

Coming Next: Sir Walter Raleigh