As Reviewed By: Ernest Hilbert

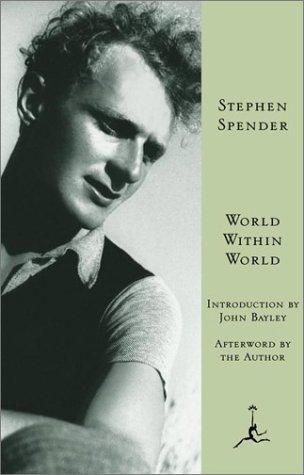

Stephen Spender’s World Within World is as much a reconsideration, a critique, of the art of autobiography as it is an autobiography. Just as Ford Madox Ford’s novel The Good Soldieris today read as an Ars Prosa, World Within World petitions its readers to consider new approaches to the genre, classifying formerly stock practices as “unnecessary convention,” including cumbersome investigations of a subject’s childhood for signs of future greatness, and delineations of otherwise irrelevant ancestry. John Bayley, one of the more eminent Oxford Dons (and, since the publication of his best-selling reminiscence of Iris Murdoch, Iris and Me, now a septuagenarian sex-symbol), has expressed the somewhat astonishing belief that Spender’s mid-life autobiography is “without any question the best autobiography in English written in the twentieth century.” Though one might instinctively presume this to be provocatively hyperbolic, there are grounds for this claim. As with Robert Graves’s brilliant memoir Goodbye to All That, World Within World is a partially fictionalized account of events, attitudes, and prominent individuals at war and at play. It is valuable for many qualities wanting in similar chronicles: Spender is disarmingly sincere in a manner quite removed from the typically feigned modesty of the English upper classes, and his appraisal of the intellectual and moral progress not only of himself but of an entire generation of English intelligentsia is uncompromising.

Stephen Spender’s World Within World is as much a reconsideration, a critique, of the art of autobiography as it is an autobiography. Just as Ford Madox Ford’s novel The Good Soldieris today read as an Ars Prosa, World Within World petitions its readers to consider new approaches to the genre, classifying formerly stock practices as “unnecessary convention,” including cumbersome investigations of a subject’s childhood for signs of future greatness, and delineations of otherwise irrelevant ancestry. John Bayley, one of the more eminent Oxford Dons (and, since the publication of his best-selling reminiscence of Iris Murdoch, Iris and Me, now a septuagenarian sex-symbol), has expressed the somewhat astonishing belief that Spender’s mid-life autobiography is “without any question the best autobiography in English written in the twentieth century.” Though one might instinctively presume this to be provocatively hyperbolic, there are grounds for this claim. As with Robert Graves’s brilliant memoir Goodbye to All That, World Within World is a partially fictionalized account of events, attitudes, and prominent individuals at war and at play. It is valuable for many qualities wanting in similar chronicles: Spender is disarmingly sincere in a manner quite removed from the typically feigned modesty of the English upper classes, and his appraisal of the intellectual and moral progress not only of himself but of an entire generation of English intelligentsia is uncompromising.

While certain (principally homosexual) disclosures came as quite a shock at the time of the book’s publication in 1951, the case of World Within World is hardly one of full disclosure. The subtlety with which he recounts particular episodes is of a kind almost entirely unknown to contemporary writers, whose apparent reluctance to withhold any information, however embarrassing or unentertaining, has gone some way in dulling their readers’ capacity to discern nuances altogether. Names are, in instances, altered, particularly when their sexual proximity to Spender would make their mention indiscreet. In cases of more public relationships, names are unavoidably retained. Finally, some characters are, by the author’s admission, types rather than distinct personalities (as with the famous example of the intolerably refined and egotistical “Communist lady novelist” encountered by Spender at the Madrid Writers’ Congress in the Spanish Civil War). While no one who moved in Spender’s circles would be particularly startled by the details of the book, the very fact that the book was published gave rise to some scandal (only many decades later could Christopher Isherwood, for example, admit: “BERLIN MEANT BOYS!”; these things were commonly bandied in their more or less rarefied milieu but were verbotenbeyond it). It was one thing to acknowledge as quietly as possible that things went on, but it was an entirely different matter when these libidinous peccadillos were shelved at the corner bookshop.

Spender’s depiction of undergraduate life at Oxford is, in some ways, not especially different from those one might encounter from any number of former Oxonians, from the classic satiric fantasy of Max Beerbohm’s Zuleika Dobson to the prudish disenchantments of Rosa Ehrenreich’s A Garden of Paper Flowers. It is really the presence of Auden that makes Spender’s Oxford years engaging. While the enduring conflict between beer-swigging athletic “hearties” and self-exilic, narcissistic aesthetes continues to this day (Spender is unpretentious enough to recognize that much of this conflict consisted of affectation on both sides, and that these poses not only grew difficult to maintain but were, to the world beyond ivied college walls, little more than dumbshow), certain waves of literary history do wash over and through the university (intermittent intellectual douching is essential). Auden was, famously, a superintending force, marshalling the artistic energies of his contemporaries as if they were military specialists: Isherwood was to be the novelist, Cecil Day Lewis and Louis MacNiece the poets, Spender the autobiographer (Auden encouraged him in this during a long walk around Oxfordshire, largely on the basis of a piece Spender had composed at age 18 about a homoerotic encounter with another English boy while on holiday in Lausanne). It is undeniable that Spender possessed a considerable aptitude for self-reflection and very balanced comprehension of both his own development and public events around him. Auden, though often off the mark (sometimes intentionally; he remarked that Americans took him too seriously, which is to say that they took him literally), was nonetheless accurate in his assessment of the young Spender’s talents in this direction.

Apart from light shed on significant contemporaries, the most likeable-and in its time provoking-facet of the book is Spender’s willingness to discuss homosexuality in a forthright and entirely unlurid manner. There are no descriptions of sexual acts, as such (that would have been considered indisputably pornographic), but Spender (who was also married twice and produced a child by his second marriage) devotes considerable attention to his affair with a young man, to whom he affixes the proletarian pseudonym Jimmy Younger; he describes the intimately emotional rather than physically carnal aspects of their relationship (though these gaps were eagerly, and as it turns out illegally, filled in by alleged plagiarist David Leavitt in his novelWhile England Sleeps a few years ago; the critic and poet James Fenton wrote to Leavitt: “An author has a right to chuck his work in the bin. That is what I would do. Quickly.”)

Spender spent his ingenuous early years after Oxford with naturalist and self-consciously modern German youths in Hamburg, where suntans, nudity, sexual promiscuity, and jazz came to form a dizzying nectar for the sensitive young poet, who already by that age was able to question: “What happened in the hearts of these people who gave themselves so easily to so many things?” He portrays an interwar generation bereft of stable moral bearings, as if waiting for a cause to take up after wallowing in endless indulgences and facile emotional relationships (Hitler was at this time barking Fascist rhetoric to sympathetic assemblies). Spender later took up residence in Berlin, at Isherwood’s behest, and entered into bohemian life in earnest. As a spectator during the mounting struggle between Communism and Fascism, which flared out from the political and economic deadfall of the First World War, Spender was immediately repulsed by the Fascists and later by the Communists as well (Spender’s polestar was truthful representation at all costs, so it is not surprising that he found particularly repulsive the Fascists’ unguarded acknowledgment that they were willing to employ lies in order to further the aims of the state).

Spain became the battleground for the two absolutist ideologies. The Republican cause was hijacked from a universal Liberal platform by Communists (who also commandeered the International Brigade) and the direct intervention of Stalinist Russia (Hitler and Mussolini threw men and materièl into the ascending firestorm to support the Fascists; England and France held firmly to non-interventionist policies). Spender’s involvement was, through the glass of his own memory, unclouded by the bravado common to personal accounts of battle, fairly prissy and irresolute. While he refused to join the International Brigade and preferred to stay clear of combat, he was willing to describe the unsurprisingly bloated fatuity of the Writers’ Congress assembled in the nearly-encircled Madrid; the presence of los intellectualesostensibly bolstered the Republican morale, but Spender depicts the Congress as a gathering of “spoiled children,” including himself in this ungenerous portrayal. Not long after setting foot in Spain (in the hopes of somehow extricating his former lover Jimmy, who had joined the International Brigade), Spender’s ideal of Communist righteousness was fractured after learning of concealed atrocities and willing blindness on the part of Party members. What emerges from this episode in his life is a more complex impression of the war, its participants, and the conduct of the previously sacrosanct Communist Party-especially after the Moscow Trials and the scandal surrounding the publication of André Gide’s Retour de l’U.R.S.S.-, of which Spender was at best a coolly-received member. He proved too sympathetic and intelligent to be swayed by the increasingly censorious and untenable Left, despite his contribution to the Left Book of the Month, Forward from Liberalism. He experienced the central crisis to befall intellectuals of the interwar period. Idealistic, sometimes effete, men and women, like Spender, Auden, and the famous editor and parodist Cyril Connolly, would eagerly formulate elaborate political agendas on paper and in cafés only to have them savagely mangled by the exigencies of political fact, by dispiriting internecine bickering in the lecture halls of London and unrestrained brutality in the hills of Spain. The ideological concerns of an entire generation of intellectual Europeans and Americans dangled over a chasm of meaninglessness in the ever-shifting fronts of the Spanish peninsula.

Spain became the battleground for the two absolutist ideologies. The Republican cause was hijacked from a universal Liberal platform by Communists (who also commandeered the International Brigade) and the direct intervention of Stalinist Russia (Hitler and Mussolini threw men and materièl into the ascending firestorm to support the Fascists; England and France held firmly to non-interventionist policies). Spender’s involvement was, through the glass of his own memory, unclouded by the bravado common to personal accounts of battle, fairly prissy and irresolute. While he refused to join the International Brigade and preferred to stay clear of combat, he was willing to describe the unsurprisingly bloated fatuity of the Writers’ Congress assembled in the nearly-encircled Madrid; the presence of los intellectualesostensibly bolstered the Republican morale, but Spender depicts the Congress as a gathering of “spoiled children,” including himself in this ungenerous portrayal. Not long after setting foot in Spain (in the hopes of somehow extricating his former lover Jimmy, who had joined the International Brigade), Spender’s ideal of Communist righteousness was fractured after learning of concealed atrocities and willing blindness on the part of Party members. What emerges from this episode in his life is a more complex impression of the war, its participants, and the conduct of the previously sacrosanct Communist Party-especially after the Moscow Trials and the scandal surrounding the publication of André Gide’s Retour de l’U.R.S.S.-, of which Spender was at best a coolly-received member. He proved too sympathetic and intelligent to be swayed by the increasingly censorious and untenable Left, despite his contribution to the Left Book of the Month, Forward from Liberalism. He experienced the central crisis to befall intellectuals of the interwar period. Idealistic, sometimes effete, men and women, like Spender, Auden, and the famous editor and parodist Cyril Connolly, would eagerly formulate elaborate political agendas on paper and in cafés only to have them savagely mangled by the exigencies of political fact, by dispiriting internecine bickering in the lecture halls of London and unrestrained brutality in the hills of Spain. The ideological concerns of an entire generation of intellectual Europeans and Americans dangled over a chasm of meaninglessness in the ever-shifting fronts of the Spanish peninsula.

It is during the Spanish War that Spender came to meet Ernest Hemingway, who had arrived to test his celebrated courage in the face of war (a disputable matter). Despite rare moments of clear-eyed literary discussion, Hemingway incessantly reverted to acting out his own characters, drinking and boasting, singing peasant songs and insisting that he did not read. Spender also spent time with André Malraux, who seems to have spent most of the war quayside sunning himself, driving in the mountains, and sitting down to gourmet meals. There are moments of decided hilarity in Spender’s accounts, and these contrast well with the over-arching sense of moral disaster occasioned by the war. Spender’s considerations around this time of T.S. Eliot’s poetry, particularly The Waste Land, are among the best ever written. Spender clarifies the role that Eliot’s poems played in shaping the literary sensibilities of The Divided Generation, made up of politically-committed authors who sought (unsuccessfully, in most cases) to keep politics out of their authorial compound.

World Within World is also very much about the closing of an era, an age of individual protest and intervention, or, more accurately, the belief that individual protest and intervention could prevent a totalitarian war in which all concerned would be forced to adopt the conditions and attitudes of fascism in order to combat it. After the collapse of the Republican government in Spain, a shadow was cast over the political purpose of Liberals and partially-committed Communists; individual moral involvement in world affairs seemed increasingly useless. After the outbreak of war with Nazi Germany-which, according to many at the time, issued directly from the Fascist triumph in Spain and the failure of democratic European powers to intercede-the individual conscience seemed to be abandoned to irresistible historical pressures:

World Within World is also very much about the closing of an era, an age of individual protest and intervention, or, more accurately, the belief that individual protest and intervention could prevent a totalitarian war in which all concerned would be forced to adopt the conditions and attitudes of fascism in order to combat it. After the collapse of the Republican government in Spain, a shadow was cast over the political purpose of Liberals and partially-committed Communists; individual moral involvement in world affairs seemed increasingly useless. After the outbreak of war with Nazi Germany-which, according to many at the time, issued directly from the Fascist triumph in Spain and the failure of democratic European powers to intercede-the individual conscience seemed to be abandoned to irresistible historical pressures:

For the time being, the only hope was that the current of power should be reversed and turned back on those who had first employed it: that the pendulum of the bombers, swinging over us, should swing back again over Germany. Yet to admit this was an admission of spiritual defeat: for it was to say that hope lay in power, in opposing despair with despair. We said this, with the result that we are still saying it. All this has implied the surrender of the only true hope for civilization-the conviction of the individual that his inner life can affect outward events and that, whether or not he does so, he is responsible for them.

During the Second World War, Spender, along with many other intellectuals, enlisted in the Fire Service. As if highly esteemed, if not beloved, of the gods, Spender’s stint was almost completely free of perilous activity: the conventional aerial bombing raids begun on Goering’s Adler Tag (“Eagle Day”, the first day of Adlerangriff, “Attack of the Eagles”) came to an abrupt end just before Spender began, and the first of the V1 “Buzz Bombs” crashed into London just hours after he left the service in 1944. He did, however, experience a very-near overshoot of one of Hitler’s vengeance weapons. It destroyed an apartment building nearby the attic lodging Spender shared with his then pregnant second wife, Natasha, who was evidently unperturbed by Zeus’s bolts.

That his gift for autobiographical description is expressed so remarkably well in poetry and fiction encourages one to believe it inevitable that an autobiography of considerable force would have issued from Spender at some point in his career. That it did so at the age of 42 presented an obstacle to some critics, who felt that he had done so too soon. Much later, at the age of 85, he defended his middle-aged decision on the grounds that he was then entering an altogether new stage of his life and felt the need to close off the former one, which was, as it were, divided both temporally and geographically: The end of the Second World War, which he saw as the end of the age, and his migration to America, to teach at Sarah Lawrence College at the behest of Harold Taylor, then president of the college. Much of World Within Worldwas written on Frieda Lawrence’s Ranch in New Mexico. His invitation by the German-born wife of England’s most impassioned and controversial novelist is fitting. The most extraordinary features of Spender’s life include his friendships with well-known personalities and their almost Dickensian tendency to turn up repeatedly throughout his life: W.H. Auden, Christopher Isherwood, Isaiah Berlin, Arthur Calder Marshall, Humphry House, David Gascoyne, Bernard Spencer, André Malraux, C. Day Lewis, Ernest Hemingway, Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, W.B.Yeats, the Sitwells (Sacheverell, Sir Osbert, and Dr. Edith), J.B. Priestly, Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz, Louis MacNiece, Edwin and Willa Muir. Spender lived what David Leeming termed, in his book of the same title, a life in modernism. Spender is the sum not only of his own creative endeavors but the social activities of which he was a part, as well as the history through which he lived. John Bayley regards the concentric worlds of Spender’s title as the world itself and the miniaturized world within the book’s covers. Spender himself describes them in the closing pages as the infinite expanses of the outside universe and equally vast depths within the human heart and mind. World Within World remains Spender’s greatest achievement, the realization of his finest qualities as critic, poet, novelist, playwright, and essayist.

That his gift for autobiographical description is expressed so remarkably well in poetry and fiction encourages one to believe it inevitable that an autobiography of considerable force would have issued from Spender at some point in his career. That it did so at the age of 42 presented an obstacle to some critics, who felt that he had done so too soon. Much later, at the age of 85, he defended his middle-aged decision on the grounds that he was then entering an altogether new stage of his life and felt the need to close off the former one, which was, as it were, divided both temporally and geographically: The end of the Second World War, which he saw as the end of the age, and his migration to America, to teach at Sarah Lawrence College at the behest of Harold Taylor, then president of the college. Much of World Within Worldwas written on Frieda Lawrence’s Ranch in New Mexico. His invitation by the German-born wife of England’s most impassioned and controversial novelist is fitting. The most extraordinary features of Spender’s life include his friendships with well-known personalities and their almost Dickensian tendency to turn up repeatedly throughout his life: W.H. Auden, Christopher Isherwood, Isaiah Berlin, Arthur Calder Marshall, Humphry House, David Gascoyne, Bernard Spencer, André Malraux, C. Day Lewis, Ernest Hemingway, Virginia and Leonard Woolf, Lytton Strachey, W.B.Yeats, the Sitwells (Sacheverell, Sir Osbert, and Dr. Edith), J.B. Priestly, Pablo Neruda, Octavio Paz, Louis MacNiece, Edwin and Willa Muir. Spender lived what David Leeming termed, in his book of the same title, a life in modernism. Spender is the sum not only of his own creative endeavors but the social activities of which he was a part, as well as the history through which he lived. John Bayley regards the concentric worlds of Spender’s title as the world itself and the miniaturized world within the book’s covers. Spender himself describes them in the closing pages as the infinite expanses of the outside universe and equally vast depths within the human heart and mind. World Within World remains Spender’s greatest achievement, the realization of his finest qualities as critic, poet, novelist, playwright, and essayist.