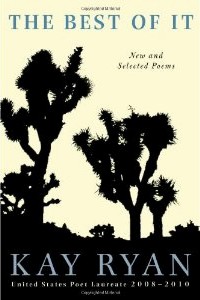

Reviewed: The Best of It: New and Selected Poems by Kay Ryan. Grove Press, 2011. 288 pages. $14.95.

Reviewed: The Best of It: New and Selected Poems by Kay Ryan. Grove Press, 2011. 288 pages. $14.95.

Kay Ryan’s pulling-herself-up-by-her-own-muddied-Blundstone-bootstraps-story is already the stuff of legend. After writing and publishing poems for 20 years or so in relative obscurity, in this last decade she became the darling of Poetry Magazine, won a Guggenheim and the Ruth Lilly in 2004, was named United States Poet Laureate in 2008, and was awarded the Pulitzer Prize in 2011 for The Best of It: New and Selected Poems. Suddenly, almost out of nowhere, she is popular and is a poetry “best seller” like Mary Oliver, with whom she has many things in common (style and subject matter not being two of them). Both are read by people who don’t read much, or any, “academic” poetry but giggle when Billy Collins is mentioned.

Kay Ryan is now about as household a name as seems possible in contemporary American poetry, but there is a good chance that in 2008, when Ryan was named Poet Laureate, even you, gentle reader of poetry reviews, scanned the headlines along with the hoi polloi and muttered, “Who is Kay Ryan?” We shouldn’t beat ourselves up too much for our ignorance, though, for if we didn’t know Kay Ryan, it was because she rather wanted it that way. You see, she’s not much like us, and she doesn’t like us. As she wrote in “I Go to AWP” (Poetry, July 2005), she had never been to the AWP, if you can fathom such a thing. This was, for her, “a point of honor”: she was not that kind of person. She was, and wished ever to be, “an outsider.” Besides, she has never taken (or even taught!) a creative writing class. Those who busy themselves with such things are, she notes in all caps, “THE SPAWN OF THE DEVIL.” They are not actually individuals but are “deadly white threads of the great creative writing fungus.” They make sentimental, whiny noises about being “nourished” and “stimulated” by young poets and obsess about the “arc” of their newest book. Throughout her ethnographic adventures among the natives, Ryan maintains her “abstract contempt” for the tribe of creative writers and most all their luminaries.

So if we didn’t know her it is because she was never much interested in knowing us. Instead of working her way up the Po-Biz ladder — winning this little prize here, publishing that important chapbook there — she toiled away in happy and noble obscurity, working for a living by teaching reading and writing at San Quentin prison and remedial English at the community college in Marin County, California. Hardly the empyrean labors undertaken on Parnassus—or Iowa City. Yet look at her now, vying with Justin Bieber and Lady Gaga on YouTube, being interviewed on PBS and NPR, reading at posh white-wine festivals, winning big prizes, and opining about all things poetical as the laurels rest heavily upon her head.

This isn’t to say she was completely unknown before. Some of her books were reviewed in respectable places, and she picked up an influential champion or two along the way. Those who wished to tell us about Kay Ryan compared her short, short-lined poems sometimes to Emily Dickinson’s, but more often to Marianne Moore’s. Some proclaimed her to be a Grandma Moses-type American Primitive or an autodidact whose “inch wide” poems are “Bible verses for the worldly.” Others found her poems as sophisticated and specialized as the atonal music of Erik Satie, Fabergé eggs, and the boxes of Joseph Cornell. Dana Gioia reportedly called her “our Elizabeth Bishop,” as if we were casting a new one, or as if the old one had dried up.

Perhaps better to dub Kay Ryan “our Adelaide Crapsey”—for, like Crapsey, Ryan is very good at writing small poems about small moments. Like Crapsey, Ryan has never written a “major” poem that could last a round in the ring with “In the Waiting Room,” “Questions of Travel,” or “At the Fishhouses.” Bishop notices everything and makes us notice it all, too. Ryan, in comparison, is like the class clown who is adept at pointing out the obvious and the obviously ridiculous. Randall Jarrell wrote of Willa Cather: “Her style has very distinct limits, but inside those limits she writes with ease and grace.” So it is with Ryan. Her métier is hitting big targets precisely. Her poems are lean and spare, rarely spilling over a printed page. They are quick, engaging, accessible flights of fancy inspired by something seen, a common phrase overheard, or some strange data in Ripley’s Believe It or Not. There are a lot of them, and they keep cropping up, profusely. I doubt we would call them “lovely” or “profound,” but they are certainly enjoyable and wise.

Ryan loves words—their materiality and their etymologies, and she has a particular fondness for homonyms, clichés, and puns. At first, her diction seems folksy and homespun, but soon enough one begins to notice an intellectual sophistication and urbane wit. As Quintilian says, urbanitas “denotes language with a smack of the city in its words, accent and idiom, and further suggests a certain tincture of learning derived from associating with well-educated men; in a word, it represents the opposite of rusticity.” Ryan is no bumpkin. And while her humor is sometimes of the pull-my-finger type, these are not poems as stand-up comedy. Her wit does not always make us laugh, and it is usually not polite, for she aims to satirize folly, mock inflated egos, and portray us as we really are. That is, Kay Ryan is serious — especially when she’s being funny, for as she wrote in “I Go to AWP,” even if she has little interest in commingling with the fungal “us,” she does seek a connection to the great tradition, and wants to write poems that will earn her “the respect of the dead.”

Ryan’s style mixes the formal with the conversational, gravity with levity. It reflects her attitude toward experience: life is tragic, but we shouldn’t take it too seriously. In this, she’s a little like Montaigne, who prefers the way of Democritus to that of Heraclitus:

Democritus and Heraclitus were two philosophers, of whom the first, finding the human condition ridiculous and vain, never appeared in public but with a mocking and laughing face; whereas Heraclitus, having pity and compassion on this same condition of ours, wore a face perpetually sad, and eyes filled with tears.

Ryan, like Montaigne, finds it “more pleasant to laugh than to weep, but because it expresses more contempt and condemnation than the other, and I think we can never be despised as much as we deserve.”

Even at her most ambitious, though, Ryan is subtle and her style is stoic: reserved, reasonable, simple, honest, lucid. She doesn’t wander about in effluvial free-associative hedonistic confusion, reflexively qualifying and negating every claim, preferring instead aphoristic brevity. She doesn’t ask her reader to be impressed by her range of imagination and depth of feelings and doubts, and we never hear the petulantly imperious I spotlighted in the contemporary, post-confessional lyric. Instead, her reader participates in a mature, moral experience of commenting on, assessing, and judging this foul and pestilent congregation of vapors. Her turns of phrase and internal rhymes display compression and nimble sophistication.

Ryan expresses much in little. Like Aesop, she delights in fabling our vices and absurd notions. If she errs in her balancing act of gravity and levity, it’s usually on the side of levity. She is at her best when juggling the pathos associated with the transience of things, as in “Don’t Look Back”:

This is not

a problem

for the neckless.

Fish cannot

recklessly

swivel their heads

to check

on their fry;

no one expects

this. They are

torpedoes of

disinterest,

compact capsules

that rely

on the odds

for survival,

unfollowed by

the exact and modest

number of goslings

the S-necked

goose is—

who if she

looks back

acknowledges losses

and if she does not

also loses.

One gets a sense here of Ryan’s ear and method—about the genesis of her poems. Perhaps hearing “neckless” instead of “necklace,” thinking begins, and a poem is born. For a less ambitious poet, this little misprision would be sufficient unto itself, and we would be regaled by how clever the poet is for noticing this coincidence as she piles on a few other homonymic puns so that we “get it.” A more admirable sort of poet than that would stop with those first three lines, creating something epigrammatic. Ryan, though, provides an argument. To be “neckless” would be a blessing: a life with no regrets, a pleasurable day without hindsight’s nagging. The otherwise unenviable physical limitations and survival tactics of sea creatures suddenly becomes a valuable pendant when hung upon this “neckless.”

Another fine poem that finds Ryan simultaneously mourning loss and mocking the impulse to cling to that which passeth away is “Things Shouldn’t Be So Hard”:

A life should leave

deep tracks:

ruts where she

went out and back

to get the mail

or move the hose

around the yard;

where she used to

stand before the sink,

a worn-out place;

beneath her hand

the china knobs

rubbed down to

white pastilles;

the switch she

used to feel for

in the dark

almost erased.

Her things should

keep her marks.

The passage

of a life should show;

it should abrade.

And when life stops,

a certain space—

however small—

should be left scarred

by the grand and

damaging parade.

Things shouldn’t

be so hard.

These kinds of meditations often lead to her composing nearly religious, and almost pious, poems: “Is it Modest,” “The Narrow Path,” “The Palm at the End of the Mind,” “Crib.” Two poems—“All Shall Be Restored” and “Swept Up Whole”—seem to consider the Rapture. Occasionally, as in “Blandeur,” she prays:

If it please God,

let less happen.

Even out Earth’s

rondure, flatten

Eiger, blanden

theGrand Canyon.

Make valleys

slightly higher,

widen fissures

to arable land,

remand your

terrible glaciers

and silence

their calving,

halving or doubling

all geographical features

toward the mean.

Unlean against our hearts.

Withdraw your grandeur

from these parts.

Life is hard. The truth is hard. And death, perhaps, will find each of us shouting our own version of “O, Solon! O, Solon!” The greatest works by the greatest writers constantly remind us of our tragedies big and small. By these tokens, we know these works are serious, and we know ourselves as the kind of serious people who deserve them. We lump their despair with ours and enjoy the company. But living well, and writing well, requires a little levity. Nature herself occasionally lays off her unrelenting destruction of things merely human to produce a hummingbird or a manatee. Thus, a great writer is like nature, or perhaps imitates nature, which is ever variable, as Ryan sees in “Dew”:

As neatly as peas

in their green canoe,

as discreetly as beads

strung in a row,

sit drops of dew

along a blade of grass.

But unattached and

subject to their weight,

they slip if they accumulate.

Down the green tongue

out of the morning sun

into the general damp,

they’re gone.

This kind of careful observation is also evident in “Cloud,” “Ledge” “Silence” and “Forgetting.”

Perhaps the closest Ryan comes to broaching a theme dear to Elizabeth Bishop is in “Learning,” about the unpleasantries of learning what is necessary, and in “The Fourth Wise Man,” where she gives another argument for why it would not have been a pity to have stayed home and not gone sight-seeing:

The fourth wise man

disliked travel. If

you walk, there’s the

gravel. If you ride,

there’s the camel’s attitude.

He far preferred

to be inside in solitude

to contemplate the star

that had been getting

so much larger

and more prolate lately—

stretching vertically

(like the souls of martyrs)

toward the poles

(or like the yawns of babies).

Even when Ryan allows herself to travel to imaginative isles and dream impossible dreams, it is not as if she has arisen now to go to Innisfree. She continues to reflect on how the tragedy of life is built into our anatomy as the essence of our being. And while it may be true, as Heraclitus says, that “There awaits men when they die things they neither look for nor dream of,” that doesn’t stop Ryan from hoping for a Paradise suited to her personality—a “Crustacean Island”:

There could be an island paradise

where crustaceans prevail.

Click, click, go the lobsters

with their china mitts and

articulated tails.

It would not be sad like whales

with their immense and patient sieving

and the sobering modesty

of their general way of living.

It would be an island blessed

with only cold-blooded residents

and no human angle.

It would echo with a thousand castanets

and no flamencos.

When Kay Ryan calls her selection of poems The Best of It, I am inclined to take her word for it. The unfortunate title comes from a poem in The Niagara River, where the phrase is used colloquially:

However carved up

or pared down we get,

we keep on making

the best of it as though

it doesn’t matter that

our acre’s down to

a square foot. As

though our garden

could be one bean

and we’d rejoice if

it flourishes, as

though one bean

could nourish us.

The best of The Best of It, besides the poems mentioned above, include: “Pentimenti,” “Finish,” and “Easter Island” from the “New Poems” section; “Flamingo Watching,” “Leaving Spaces,” “How Successful Can She Afford to Be?” “Les Natures Profondement Bonnes Sont Toujours Indécises,” “So Different,” and “Impersonal,” from Flamingo Watching; “How Birds Sing,” “Outsider Art” and “Heat,” from Elephant Rocks; “A Hundred Bolts of Satin,” “That Will to Divest,” “Great Thoughts,” and “The Job,” from Say Uncle; and “Hailstorm,” from The Niagara River.

Kay Ryan is a poet who knows what she is doing, and she does it compulsively. In Ryan’s career, there are no great changes, no political or religious conversions, no switching camps or styles, no public stands on public causes. If there is any development in her oeuvre it is slow and nearly imperceptible, like a single tone added to a theme by Philip Glass: so unobtrusive we hardly notice it, but once we do, we can’t remember it not being there.

Some have worried out loud about Kay Ryan’s influence on the future practice of contemporary poetry. They shouldn’t. American poetry could use a dose of restraint and humility, and Ryan would be a good tutor for young poets who care more about the “moral evaluation of human experience,” as that old crank Yvor Winters said, than crowing about how interesting each one of their fleeting thoughts, dreams, or memories are. More worrisome is the influence of the schizophrenic strings of nonsense popular these days, and the rambling I-look-out-the-window-and-see-X-which-reminds-me-of-your-body style, which is much more easily imitated by the young than the seemingly simple, plain style poems of Kay Ryan. Her poems often resemble the method she describes in one of her many ars poetica, “How Birds Sing”:

One is not taxed;

one need not practice;

one simply tips

the throat back

over the spine axis

and asserts the chest.

The wings and the rest

compress a musical

squeeze which floats

a series of notes

upon the breeze.

“For that plainness of style seems easy to imitate at first thought,” says Cicero, “but when attempted nothing is more difficult.” Thus, the influence of her songs may be a salutary, sobering, and rectifying—if they can be heard over all the noise.

Photo credit by Christina Koci Hernandez.

Kay Ryan’s poems seem almost devoid of craft.

Pingback: The Gravity and Levity of Kay Ryan | Joines Reviews

Nice and wonderful work.

A just estimation of Kay Ryan’s poetry, and its relationship to predecessors and the contemporary American poetry scene. Too often I think of her work as too small, and forget that small is a giant corrective to ego.