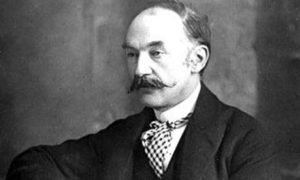

Thomas Hardy is still far better known as a novelist than he is as a poet. Although certain poems have lodged themselves where, as Frost put it, they will be hard to get rid of, there is still a widespread conviction that much of his poetry is either awkward, difficult or just downright bad. And this despite such influential voices as Philip Larkin, who declared that he “would not wish Hardy’s Collected Poems a single page shorter,” and that he regarded it “as many times over the best body poetic work this century so far has to show” (said in 1966).

I put myself firmly in Philip Larkin’s camp and say that Hardy has the unique distinction of being both a major novelist and a major poet: one of the greatest novelists of the 19th century and one of the greatest poets of the 20th. It is difficult for a critic to resist the alluring simplicity of this neat chronological distinction between the two sides of his literary career but perhaps we would do well to be cautious of drawing too many conclusions from this see-saw like vision of his artistic development. It would be risky to think of him as passing promptly from being a Victorian novelist to a Modernist poet. The other temptation is to pull the blanket brusquely to one side or the other, in an attempt either to see his novels as audaciously proto-Modernist or his poems as quaintly and nostalgically post-Victorian. Either interpretation grossly simplifies the writer.

However, the wish not to create too great a division between the novelist and the poet is comprehensible. This is not only because Hardy was writing poetry all through his novel-writing career, even if he published very little of it; it is principally because he brought to his poetry all the skills that he had acquired over decades of writing prose-fiction. I am not only talking about his narrative poetry – although I would declare that he is one of our greatest narrative poets, whether in his extended and compelling ballads like A Trampwoman’s Tragedy or in the pithy ironic anecdotes of Satires of Circumstance. Even his lyric poems acquire much of their power from his gift for creating a sharply focused point of view (often a “glimpse”, as he puts it in Satires of Circumstance) and for evoking a scene with dramatic implications. There are many poems that seem to gesture towards the novels, like “Midnight on the Great Western” (the poem provided a title for an excellent thriller by Michael Innes, The Journeying Boy), which seems like an excised scene from Jude the Obscure, or “The Rash Bride”, which provides an alternative and grimmer version of the opening scenes of Under the Greenwood Tree, or such poems as “The Lost Pyx” and “Tess’s Lament”, which make explicit reference to Tess of the D’Urbervilles. Everywhere his poetry shows the imprint of the novelist who knew the strategic importance of the telling detail, whether in creating an intriguing psychological mini-drama (see, for example, “The Workbox”) or a haunting picture of the natural world (“The Fallow Deer at the Lonely House”).

At the same time no poet of the twentieth century seems so alive to the possibilities that poetic forms offer; even a casual flick through the Collected Poems provides a stimulating overview of the great variety of stanza-forms he adopted. If Modernism’s prime task, as Pound put it, was to “break the iambic pentameter”, Hardy had already shown that he scarcely needed it himself; he only ever used it at length in the purely narrative parts of The Dynasts, the parts that are now (not without reason) least read. If readers have sometimes complained of the unrelenting gloom of Hardy’s vision of life, they have no reason to complain of any lack of variety in the forms of his poetry. And it is not only a question of changes in stanza-shapes or rhyming schemes; as with all great poets, variety in form means also variety in matter, mood and message. While no-one can reasonably deny that Hardy’s view of things is overwhelmingly bleak, the poems have an unmistakeable energy and passion. Florence Hardy’s remark to a friend, that her husband was at that moment “writing a poem with great spirit […] needless to say, it is an intensely dismal poem”, is well-known. It is this “great spirit” that comes across so strongly to us in these poems, and the technical ingenuity of the forms is just one manifestation of it.

The essays collected in this issue all testify to the ways in which this great spirit still makes itself felt to readers today. The essays arise out of the critical seminar that was held in June this year at the annual West Chester University Poetry Conference; for the last few years seminars have been held focusing on the achievements of individual twentieth-century poets (recent names include Yeats, Auden, Larkin, Bishop and Frost). Each participant in the seminar presents a paper on a single poem, which leads into general discussion. As there were thirteen participants at the Hardy Seminar this year, that left 934 of the poems undiscussed. Nonetheless, the papers presented on the handful of poems we did talk about (obviously with frequent cross-reference to other works, including the novels) managed, I think, to give some idea of the variety and profundity of Hardy’s great body of work. In this selection from the seminar Bruce Bennett opens the way with a fresh and lively analysis of what is perhaps Hardy’s most anthologised poem, “Darkling Thrush”, and this is followed by Meredith Bergmann’s closely documented study of one of Hardy’s “public poems” (“Convergence of the Twain”). David Katz offers a highly personal and effective reading of an early poem (“Neutral Tones”), while Nick Friedman gives a perceptive reading of Hardy at his very darkest, right from the title itself (“In Tenebris”). John Foy spiritedly takes on another widely discussed poem, “During Wind and Rain”, while my own paper discusses Hardy’s relations with his friend and mentor, the dialect poet William Barnes.[1]

Meredith Bergmann points out that the notion of “convergence” is central to Hardy’s vision of life. His novels and poems, as Hardy’s shrewdest critic, John Bayley, has noted, are always centred on encounters. Whether it is the shock of ship and iceberg or, on a smaller scale, of mail-cart and horse, as at the beginning of Tess, or of furtive hedgehog and musing man on a “mothy and warm” night, the encounters can lead to great disasters, personal tragedies—or even just fruitful meditations. Hardy’s job is always to report these encounters, faithfully and movingly. In the novels he presents the outcome (usually tragic) of such clashes, pursuing things to their bitter end. In the poems he often limits himself to reporting the encounter, stimulating the reader’s imagination so that it goes beyond the scene immediately created and begins to picture the consequences; Hardy, that is to say, prods us into creating the novel beyond the poem for ourselves. These essays, which can themselves be seen as critical encounters with Hardy’s poems, represent an attempt to engage in such creative activity, even if dealing only with a handful of poems. It is to be hoped, however, that they will stimulate readers to engage with the great world of Hardy’s Collected Poems. This world may call itself Wessex, and certain quaint place-names may recur in it (Mellstock, Casterbridge…), but there is nothing quaint or provincial about it. All of human – and, indeed, non-human – life is there.

[1] The other papers at the conference, which I hope will soon be published, were by Daniel Brown (“In the Moonlight”), Christine Casson (“The Going”), Robert Crawford (“A Spot”), Heidi Czerwiec (“The Voice”), Sunil Iyengar (“At the Dinner Table”), Tim Murphy (“Proud Songsters”) and Joyce Wilson (“The Self Unseeing”).