When was man first freed from the drudgery of earning his income? And who was the first to dedicate himself to the art of living well? At what point in history did an entire leisure class of hedonistic egoists first appear? And what is dandyism after all? It is merely an excessive delight in clothes and fashionable living?

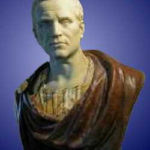

There is a long and colorful history of dandyism. Such men have always appeared, it seems, during eras of luxury and excess, whether during the Days of the Caesars, or the Age of the Virgin Queen. They have gone by many names. During the Restoration of King Charles the Second, they were “bucks” or “beaus” or “exquisites” or, more meanly, “fops.” During the Regency, they were “rakes” and “blades.” Throughout La Belle Epoque, they were “aesthetes” and “dandies.” This last name has become their common name—and a term used as both description and reproach.

The dandy has always inspired mixed feelings among his fellow citizens. According to Baudelaire, the dandy has a “burning need to create for himself a personal originality.” Such characters incite envy or contempt among their fellow man: it is a “burning desire” which strikes others as too ambitious or arrogant. The dandy has always been unmoved by such resentment; the pursuit of “idle perfection” is not done for applause. As Robert de Montesquiou once said (and his indifference to criticism could be called archetypal): “It is better to be hated than to be unknown.”

We will not concern ourselves with dandies who wrote little of consequence –great though they were in their manner of life – such as Alcibiades or Beau Brummell. It is too much off the point to entertain the anecdotes that surround such figures, not to mention their peers such as the Duke of Buckingham, or Ludwig the Second (the Swan King of Bavaria), or the Counts Boni de Castellane or d’Orsay. Examples are too abundant. As one author reminds us:

At one period of English history the whole population of the country was divided between dandies and anti-dandies, Cavaliers and Puritans, the former dandified in dress, religion, methods of fighting and in morals. They were great dandies those martial Cavaliers, and so were a few of their successors, who flirted and frivoled at Whitehall under Charles II.

Indeed, there have been periods of such widespread dandyism—in England during the Restoration and the Regency, and all along the Continent during La Belle Epoque—that it becomes a little hard to isolate the strains of so influential a social movement.

Over the next month, we shall therefore concern ourselves with the Great Dandies of Literature. From Plato to Petronius and from Byron to Wilde, we shall examine and celebrate those writers who strove for what Yeats (in his poem “The Choice”) thought impossible: perfection of the life, and of the work. Enjoy.

Suggested Reading:

The Satyricon by Petronius

The Anatomy of Dandyism by Barbey d’Aurevilly [Du Dandysme and de Georges Brummell; published 1844]

The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm by Ellen Moers

The Luck of Barry Lyndon by William Thackeray

A Rebours by Joris Karl Huysmans

Sartor Resartus by Thomas Carlyle

The Picture of Dorian Gray by Oscar Wilde

Suggested Links:

http://www.dandyism.net (A veritable treasure trove of dandy scholarship.)