Thomson William “Thom” Gunn (1929-2004)

As Reviewed By: Ernest Hilbert

It will be frequently remarked elsewhere that the past year saw many fine poets cross the bar, but only one of them devoted huge energies to poems about young men crossing barroom floors. The Anglo-Californian Thom Gunn, who died this year at the age of 74, has been everywhere memorialized and for an expectedly diverse assortment of reasons, or causes, as they may be. In native quarters, he was beloved of his generation of English poets, an heir of Auden, a dashing young man who composed elegant poems about motorcycle gangs and smoky rooms in books like Fighting Terms and The Sense of Movement. However, the height of his popularity in the United States came later, with his enormously popular book of elegies on the first major ravages of the AIDs epidemic in the 1980s, Man With the Night Sweats. What appeals to these two transatlantic groups of readers might be quite distant when seriously considered, but the quality in Gunn’s poetry that magnetized them both is an exquisite combination: English grace and American coarseness (for lack of finer terms in both cases). He set more poems in rough bars than probably any poet aside from Charles Bukowski, who specialized in tales from that boozy milieu.

It will be frequently remarked elsewhere that the past year saw many fine poets cross the bar, but only one of them devoted huge energies to poems about young men crossing barroom floors. The Anglo-Californian Thom Gunn, who died this year at the age of 74, has been everywhere memorialized and for an expectedly diverse assortment of reasons, or causes, as they may be. In native quarters, he was beloved of his generation of English poets, an heir of Auden, a dashing young man who composed elegant poems about motorcycle gangs and smoky rooms in books like Fighting Terms and The Sense of Movement. However, the height of his popularity in the United States came later, with his enormously popular book of elegies on the first major ravages of the AIDs epidemic in the 1980s, Man With the Night Sweats. What appeals to these two transatlantic groups of readers might be quite distant when seriously considered, but the quality in Gunn’s poetry that magnetized them both is an exquisite combination: English grace and American coarseness (for lack of finer terms in both cases). He set more poems in rough bars than probably any poet aside from Charles Bukowski, who specialized in tales from that boozy milieu.

The Times of London praised him as one of the past-half-century’s “shrewdest moralists.” This is surprising given his unabashed openness about hard drug use (inspired by his friend Paul Bowles) and especially casual sex, but there is something to it. Once the alleged shock of his subject matter has worn off, Gunn may be remembered largely as a poet of relationships, or to be more specific, as a poet concerned with the great questions attending love and permanence of affection when these two ragged glories are rubbed up too often against fantasy and straightforward lust. The view from across the Atlantic is telling, as the Times goes on to relate that “his reputation wavered after his move to the United States,” just as his estimation stateside warmed up. It is impossible to know if this is due to stylistic changes or a sense of abandonment that must have begun to afflict the Sceptred Isle around this time. The previous generation of British readers grew noticeably less chummy with Auden after his decampment, though this had the tinge of patriotic justification given that Luftwaffe bombs were pounding holes in the dome of St. Paul’s while Auden took cocktails at his Greenwich Village local. It is likely that some of Gunn’s original readers migrated away due to his bald descriptions of sex rather than his choice of address, though one is inclined to believe that some small burr of betrayal stuck in the British lion’s paw. But then, who would prefer damp tweed and warm ale on a rainy afternoon to a new world where

Birds whistled, all

Nature was doing something while

Leather Kid and Fleshly

lay on a bank and

gleamingly discoursed.

Gunn is also a poet of movement. Not a poet of travel, as such, but of constant change and the freedom tendered by refusal to set foot down firmly or cling to the past. There is freedom in movement, but it should be recalled that Gunn never had a steady family life in which he might stake an identity. His parents divorced when he was still young, and his mother committed suicide. He spent most of his student days at University College School living with friends and aunts. He grew to be at bitter odds with his father. The two men who finally exerted a lasting influence in his life were two giants of literary criticism: F. R. Leavis, while Gunn was at Trinity College Cambridge, and Yvor Winters at Stanford. A third figure, shadowy with historical distance, is John Donne, whose metaphysical intensity and wit lather many of Gunn’s better poems.

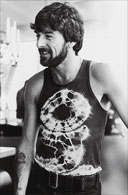

It is no revelation that Gunn’s early poems owe a debt to Auden. The tight-fisted and elusive diction of his first books never really disappears, even if the later poems tend to be more freely constructed and easier to comprehend on a first pass. This is a development in style that makes sense across both geography and time, in this case from Cambridge to San Francisco, from the buttoned 1950s to the bare-chested 1970s. Wolfgang Saxon wrote in the New York Times that in addition to writing primarily in inherited poetic forms, Gunn “experimented with free verse and syllabic stanzas. In doing so he evolved from British tradition and European existentialism to embrace the relaxed ways of the California counterculture.” This is true, but it also misses the point. He kept every inch of the British tradition while sunbathing on the deck with a daiquiri. Gunn’s dry formal style can be matched with that of his superior contemporary, Philip Larkin, but it is hard to imagine them sharing much else aside from an antipathy to the grand pronouncements of the high modernism that came before them. Unlike the perpetually disappointed and homely author of The Less Deceived, Gunn seems every stitch the charming, tanned beach boy, sometimes with bleached hair, sometimes as a robust, weathered brunette, as in the dazzling 1980 photograph by Robert Mapplethorpe. Richard Tillinghast placed his finger square in the critical knot that is so often pulled taut around Gunn when he remarked of the poet’s ability to bring “to demotic experience the classical clarity of his finely honed meter and incisive rhymes.” While it would be a mistake to assume that such a prolific poet can be summed only according to this formula, it is true that the larger share of his career can be snugly positioned this way.

While the second half of Gunn’s career was spent sometimes grappling homoerotic themes head-on, it is difficult to balance the image of him as a gay poet, strictly speaking. He is an Anglo-American poet, a post-war British poet, an experimental formalist, a poet who addressed the AIDS crisis and homosexual desire, but no single description works well by itself. This probably has a lot to do with the era in which he grew to prominence. He was well known as a poet on the jamb of greatness before he shouldered the closet door open. Also, he did not have to publish primarily in anthologies devoted to homosexual poetry in order to gain an audience. As a young poet today, he probably would. There is no question that homoerotic subjects stand out in his poems, but he is not entirely overwhelmed by these matters. The primary role of sex in his poems is to illuminate the ancient struggle between body and mind.

The bright young thing, the Oxbridge undergraduate is never cast entirely out of the garden party by the flaming sword of middle age experience. In the 1980s Gunn continued to publish poems of poise and nearly quaint allure, as in his invitation to his brother: “Dear welcomer, I think you must agree / It is your turn to visit me.” Like his countrymen Christopher Isherwood and David Hockney, Gunn was drawn to the sunburnt freedom of California, where cultural traditions were still young and malleable and class lines blurred beyond all distinction. While more conservative poets like Auden never got much past New York in their American pilgrimage, San Francisco seems more apt for Gunn’s generation. The Bay Area is as far as one can go, in many regards, before bouncing back the other way again or dropping nose-first into the Pacific. While he may seem comfortable writing on naturalist themes (“The Life of the Otter”) as on rough trade in the Castro district (too many to name), one should remember that his otter is behind glass at the Tucson Desert Museum. What this tells us about his relationship with his subjects is open to discussion, but one imagines that the objects of his closest attention were in no way distant from his embrace, if not his heart.

Peter Campion remembers Gunn as a poet “known for his daring subject matter,” though aside from his last book, Boss Cupid, which was released after his Collected Poems, Gunn’s selection of topics seems downright staid by today’s standards. In his first book, 1954’s Fighting Terms, he wrote in “Carnal Knowledge” of how “even in bed I pose,” and in “On the Move” of the motorcycles whose “hum / Bulges to thunder held by calf and thigh.” These statements were perhaps remarkable in their day, when a knotty Robert Frost was the most famous living American poet and the rumpled Auden lorded it over his own factions, but they are almost timid when set alongside the fumes and related leaks of the Beats in the same decade, even if Gunn shares some of their shameless abandon, their adolescent excitement, hanging out at “another all-night party” hearing its “angelic messages.” He is also a better poet than any of the principal Beats, even if he is less an object of dreamy nostalgia for young hippies. Gunn does not incessantly attempt to frighten the squares for the sake of it, and he also bore his observations out to more mature conclusions: “I said our lives are improvisation and it sounded / un-rigid, liberal, in short a good idea. / But that kind of thing is hard to keep up.” You can’t see very far with a lampshade on your head. The party may never have to end, but we all have to drag ourselves home at some point.

The general loosening of Gunn’s style can be best viewed in two poems written on the same subject decades apart, both of them ruminative gazes at The King. “Elvis Presley,” from the 1957 collection The Sense of Movement, sees syntax wound tightly around the grille of iambic pentameter stanzas:

Two minutes long it pitches through some bar:

unreeling from a corner box, the sigh

Of this one, in his gangling finery

And crawling sideburns, wielding a guitar.

Compare this formal muscularity to the more droll buoyancy of “Painkillers,” from the 1982 collection The Passages of Joy:

The King of rock ‘n’ roll

Grown pudgy, almost matronly,

Fatty in gold lame,

mad King encircled

by a court of guards, suffering

delusions about assassination,

obsessed by guns, fearing

rivalry and revoltpopping his skin

with massive hits of painkillerdying at forty-two.

The second exercise is both more straightforward and much closer to the glitzy kitsch of Presley, but these poems also refract a smaller historical difference: the lithe, black leather clad Elvis was in many ways magnificently new and even threatening, while the late-career star was in serious decline and damned to forcibly parody his own golden beginnings right up to his own tragicomic ending. The second is also more interesting in that it casts Elvis in the role of a loopy King Ludwig II of Bavaria while also bitchily pointing up the stylistic grotesqueness that resulted when our homegrown King became as bloated and dull as any pre-Revolutionary courtier. The second is more fun to read, but it yields less. Perhaps part of Gunn’s point is that the deflated diction and metrics match the sequined Presley’s spongy waistband, but the poem seems less successful than the earlier, tight-fisted one that demanded so much and released so little of itself. The author of the first poem, the sullen punk, aping Brando, will not make eye contact and speaks in monosyllables, yet he exudes an allure of danger, even mystery. The elder man behind the second poem, chic, articulate, is more agreeable but does not exert quite as much of a hold on our imagination. Both styles have their merits, and neither one entirely represents a complete stage in Gunn’s career, but the shift is one that has larger implications for poetry over the past five decades. Happily, however, despite some free verse sorties such as “Painkillers,” Gunn continued writing in tight forms right up to the end of his career.

Of all poets who have recently passed, Gunn is among the most deserving of elegies, given his talent along these lines. His superb elegies include “To Isherwood Dying” and “To the Dead Owner of a Gym.” It is nearly impossible to be stylish when facing the terrifying reality of death. There are fewer and fewer choices to be made. Gunn was one of the last of his kind, the last of a post-war generation of English poets reeling from the Second World War and struggling to twist out from the shadows cast by Eliot, Pound, and Auden, and then revel in the dazzling liberties afforded by the 1960’s and 70’s. He was also one of the last significant poets to write convincingly in clear forms with whole rhymes, unconcerned with the peril of quaintness that these might suffer. He held an uninterrupted prosodic thread that extended all the way back to Chaucer, unlike the American New Formalists who are compelled to scrabble together a new movement amid the savages, as they see it. Right up to the end, as in “Death’s Door,” Gunn demonstrated a willingness to take real risks in employing traditional rhetorical flair:

Of course the dead outnumber us

– How their recruiting armies grow!

My mother archaic now as Minos,

She who died forty years ago.

He dared to write Ogden Nash-like witticisms, as with the two line “Jamesian”: “Their relationship consisted / In discussing if it existed.” These chimes are no longer to be heard from such a confident and talented voice, and they will be missed. Gunn’s poem about J. V. Cunningham is a mirror that can easily be spun back to describe its author. It is also a fitting farewell:

He concentrated, as he ought,

On fitting language to his thought

And getting all the rhymes correct,

Thus exercising intellect

In such a space, in such a fashion,

He concentrated into passion.