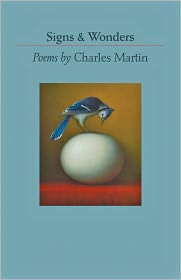

Reviewed: Signs and Wonders by Charles Martin. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011. 74 pages.

Reviewed: Signs and Wonders by Charles Martin. The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2011. 74 pages.

To publish a collection of new poems late in a distinguished career is a slightly anxious proposition, both for the poet and for readers. This is even more true when the previous book, nine years old now, was a “new and selected,” a gleaning of the best from previous books, along with a section of new work, looking like the summing up of a whole oeuvre. The anxious question is not, Can he still do it? As the poet’s interests shift, perhaps sharpening, perhaps deepening, we also want to know if he will still train his eye on the same matters that meant so much to us before.

That at least was the way I came to Signs and Wonders. The book is Charles Martin’s fifth original collection (besides two volumes of translations, from Catullus and Ovid), and his first since Starting from Sleep in 2002. I wanted most to know whether anything in the new work would shake me the way I am shaken by “Easter Sunday, 1985,” which opens with an epigraph:

To take steps toward the reappearance alive of the disappeared is a subversive act,

and measures will be adopted to deal with it.

—General Oscar Mejia Victores,

President of Guatemala

In the Palace of the President this morning,

The General is gripped by the suspicion

That those who were disappeared will be returning

In a subversive act of resurrection.

Why do you worry? The disappeared can never

Be brought back from wherever they were taken;

The age of miracles is gone forever;

These are not sleeping, nor will they awaken.

And if some tell you Christ once reappeared

Alive, one Easter morning, that he was seen—

Give them the lie, for who today can find him?

He is perhaps with those who were disappeared,

Broken and killed, flung into some ravine

With his arms safely wired up behind him.

It’s a wrenching statement in sonnet form, combining political and religious despair with a clear declaration that holiness is on the side of the murdered. It’s also one of Martin’s most anthologized poems, and asking for something to equal it is a large demand. Nothing in the new book is quite like it, but nothing tries to be. The world to be considered has changed, and Martin’s way of considering it in this book is to step back, to take the long view, to mull and ponder. He announces the intention in the little introductory poem, “Directions for Assembly”:

Signs is a noun (as in DO NOT DISTURB);

Wonders (as in “with furrowed brow”), a verb.

He does his wondering about the chosen signs in a masterly variety of well-chosen forms, as before, though in a different mix.

I will hazard a guess that one piece of history marks a difference between the old collections and the new one. It’s likely that Starting from Sleep was prepared for press before September 11, 2001; it’s nearly certain that its poems were written before that event, since a turn-of-the-millennium poem appears in the present new book, not the old one. The whole of the new book is tinged, in a way, with that tragedy: with history, with the pall of mortality, and even with a special, nostalgic lingering on the neighborhoods of New York City.

If I look for specifically political poems, the only one I find in the new book is unlike “Easter Sunday.” But then so is the quotation it takes off from: George Bush’s “I am the decider, and I decide what’s best.” The words are a puffed-up inanity, rather than a death threat, and they don’t invite the use of heavy-artillery religious metaphor, but the sniper rifles of satire. Martin picks the perfect metrical and formal tools: he puts the presidential voice in mincing tetrameter, shaped into three triolets, a form that forces the inanities to repeat and magnify themselves:

The ones we bomb to liberate

Have really got an attitude:

Despite the care we demonstrate

The ones we bomb to liberate

From tyranny respond with hate:

How’s that for sheer ingratitude?

The ones we bomb to liberate

Have really got an attitude….

The poem’s first appearance was in Iambs and Trochees, sadly now defunct but once a good place for lightish verse. But other poems in the book are even better examples of Martin light—actual light, with a wry take on life in all its darkness. The book ends with such a poem, called “Poison,” and I can’t decide whether this placement was wise, since it’s a precipitous drop in tone from the high seriousness of the poem just before it, about which more later. “Poison” uses the stanza form of Burns’s “To A Louse,” which helps it to borrow the tartness of Burns’s amused detachment. And it isn’t above rhymes like these:

For others an unsought egress:

Many an ogre and ogress,

Whose motto was “Only agress!”

Were shown the door

(Some regarding this as progress)

By hellebore.

The poem works through a catalog of every deadly substance and the various modes and reasons for ending it all. But it ends, and the book ends, in the genuinely Epicurean mode of everyday wisdom:

For, as John Maynard Keynes once said,

In the long run, we are all dead.

Until that happens, eat your bread

And drink your wine

And lie with your love close in bed,

As I with mine.

Most of the book is more sober than this, and sadder. There are exceptions—the sonnet “The Spaniard,” a translation from Belli, is a huge grin—but on balance the book is a thoughtful read. One of the most poignant meetings of the personal with the historical/political comes to us in a translation: “Ovid to His Book,” a rendering of the first book of the Tristia (one of several works about the poet’s exile). The longing for home, the pain of having offended power (what did Ovid do to deserve exile? the poem never explains), the discomfort of knowing the book’s shortcomings, all come clearly and gracefully through in the pentameters, rhymed in this case, that Martin favors for reworking classical poetry. In an essay in the Fall 2010 issue of Blackbird, “A Classic in Paraphrase,” he gives a handy explanation, with illustrations, of his reasons for preferring to translate Latin in pentameter, rather than either to stretch the words out into Latinate meters or to lop them down to a modern mindset and free verse. He prefers, as his title says, paraphrase—the poet’s sense made real for moderns, rather than his exact words, so that he has Ovid saying to his book

Say what you need to and then say no more.

Say nothing of what I’m being punished for—

how long do you imagine I’d survive

if I were to lead off The News at Five?

When biting words offend you, just recall

the best defense is often none at all,

and if you’d really have my exile end,

go find us both an influential friend….

Although Martin prefers English meters for translating Latin poems, he uses plenty of classical meter—sapphics and alcaics—in original poems that meditate on irony, a headstone inscription, and works of art. He uses plenty of metrical variety of all kinds, including Old English alliterative meter. This alliterative poem is the one piece I have a minor formal quibble about, possibly a bugbear of mine: Like other contemporary formalists, Martin seems to have internalized a rule for this form that demands at least three alliterating words in every single line. Look at a genuine Old English poem like Deor and you’ll find that many lines make do with only two, as Auden often did in The Age of Anxiety. It’s also possible for an Old English alliterative line to have two different alliterating pairs. The “always-three” rule can make for a stuffed feeling, and in spots the very formal, Latin-derived diction of this poem increases that feeling. I like the poem best near its end, where it settles into simple words and looks at its own doings, saying of the world’s chaos,

With woven words we ward it off

Over the silence: caesura that stands for

The fell fissure we feel underfoot

The book’s metrical and formal variety is a joy in itself. Although I was sad not to find the bouncy, bucking heterometric patterns of “E.S.L.” anywhere in this book, I still found plenty of surprise. And the variety is not simply its own excuse for being: the heroic couplets, classical meters, terza rima, alliterative-accentual form, and even the Burns pattern all seem chosen to be in conversation with the past, which is the book’s center and still point. Good as it is for formal poets to give us a break from iambic pentameter, in this book the long, quiet pentameter ruminations provide the greatest pleasures. “Brooklyn in the Seventies” is full of local and temporal color, and its nostalgia is for my own salad days too, so I’m a sucker for it. But the poem is much more than nostalgic: it’s a meditation in ten-line rhymed stanzas on the meaning of so much change, and on the way “selves were in a frenzy of commotion” during those years. “Near Jeffrey’s Hook” is a study in heroic couplets of a New York neighborhood, defined by a river and a bridge, and focusing on the physical changes to the area and the comings and goings of the people in it. And “After 9/11,” the next-to-last poem in the book, uses a deliberate terza rima to blend the distant history of a lost battle of the Revolutionary War with the horrors of 2001, which are somehow both vivid and already fading. It ends on the thought of the unknown remains that mark both events: “In our city built on unacknowledged bones.”

“After 9/11” is alone worth the price of the book and will repay many readings, but all the poems share important virtues. They’re sonically pleasing and rich in allusion, but they’re also direct. Here there are no cryptic, difficult poems on the attack. Nothing here is pointless, and much is beautiful. All works toward a fruitful clarity and invites us to think hard about what bones we and Martin have built on.

A very good and elucidating overview of this book. Made me put it on the list of to buy a.s.a.p. Thank you.