An excerpt from “The Last of the Dandies”

Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, June 1862

Article unsigned

“Who is Captain Gronow?”

He is the last of the “Dandies” of the Regency of George IV.; the sole survivor—unless we except the present octogenarian Prime Minister — of the favored mortals who, forty years ago, danced at Almack’s with the fair and frail Lady Jersey; dined at White’s with Alvanley, Kangaroo Cook, Hughes Ball, Red-Herring Yarmouth, and other worthies who have long passed the Styx; who had looked with hopeless envy upon the wonderful coats and miraculous cravats of Beau Brummell and Gentleman George; who knew the men who had penetrated the sacred mysteries of Carlton House; and who never appeared by daylight until afternoon, when the world was sufficiently aired for their advent.

In 1812 Gronow, a lad fresh from Eton, received an ensign’s commission in the Guards, was sent to Spain, where he showed pluck and spirit; went back to London and was admitted to the most select circles of fashion, being one of the half dozen out of three hundred officers of the Guards who had vouchers for Almack’s, whose sacred portals were jealously watched by the lady patronesses; and which no mortal man might pass except in full dress. Wellington himself, coming in trousers, was once remorselessly turned back. Gronow now speaks somewhat irreverently of the seven lady patronesses, whose smiles or frowns forty years ago consigned men and women to happiness or despair. Lady Jersey’s bearing was that of a tragedy queen, while attempting the sublime she frequently became ridiculous, being inconceivably rude, and often ill-bred. Lady Sefton was kind and amiable; Madame de Lieven haughty and exclusive. Princess Esterhazy was a bon enfant — a “good creature;” Lady Castlereagh and Mrs. Burrell, now Lady Westmoreland, were de très grands dames—“mighty stuck-up ladies.” The most popular of all was Lady Cowper, now Lady Palmerston.

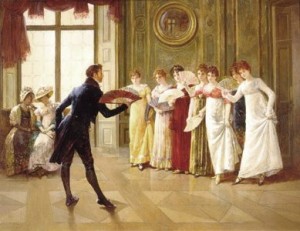

Gronow gives a curious picture, representing one of the first quadrilles ever attempted at Almack’s. The ladies wear short-waisted, tight-fitting dresses, which give the impression of a total absence of undergarments. The gentlemen wear knee-breeches, and pumps, with square-tailed coats. The Roman-nosed personage whose head is well thrown back, as if to prevent his eyes from being gouged out by his pointed shirt collar, is the Most Noble the Marquis of Worcester. The lady whose hand he holds is the fair and frail Lady Jersey, high-priestess of the shrine of fashion. The active youth who kicks up his heels like a young colt, while he gallantly bends over to kiss the hand of his partner, is Clanronald Macdonald, otherwise unknown to fame. The lady who wheels around on tip-toe is Lady Worcester.

These delights were rudely interrupted. Napoleon broke loose from Elba, and the English cavalry were sent to encounter him. Young Gronow’s battalion was to stay at home; but General Picton, yielding to his importunity, consented to take him on his staff. A proper outfit was wanted, and the youth’s funds were at low ebb. He borrowed £200, with which he rushed to a gambling-house, and staking the money won £600 more. With this he fitted himself out in becoming style and set off. He had his share in the fight of Waterloo, accompanied the army to Paris, where he enlarged his knowledge of “life;” then went back to London to renew with fresh zeal his career as a dandy Guardsman. If not one of the great lights in the dandy firmament, he had yet a recognized place in it. His portrait in time appeared in the print-shop windows in company with those of Brummell, the Regent, Alvanley, Kangaroo Cook, and other worthies. It represents him, we should say in 1825; a dapper, be-frogged figure, with tightly-strapped trousers, silly face, and comical hat. And now, an old man of threescore and more, he sits down to give the world some account of his recollections of the great men and lovely women of his early days.

He writes in a dawdling, slip-shod style, worthy of Major Pendennis; but here and there manages to give an anecdote or sketch worthy of notice as a part of the picture of the times. To do the old Dandy justice, there is little of grossness in his anecdotes and reminiscences, though the men and women of whom he speaks were, with hardly an exception, as debauched and dissolute a crew as the world ever saw. Gluttony, drunkenness, gambling, and debauchery were the rule of their lives. Statesmen and judges went regularly drunk to bed; a “six-bottle-man” was looked up to with reverence; every man in “society” expected the gout, and made the pill-box his constant companion. Few of the names which appear in the history of the times are wanting in the scandalous chronicles of their day.

We have named gambling as one of the characteristics of the age. Young Gronow risked his borrowed £200 at the card-table. But this was nothing to the high play which prevailed at the clubs. Fox once played twenty-two hours in succession, losing £500 an hour. His losses in all amounted to £200,000. The Salon d’Etrangers in Paris offered to the English visitors abundant facilities for play. It was kept by the Marquis de Livry, who received his “guests” with a courtesy which made him famous throughout Europe. He was in looks the counterpart of the Prince Regent, who sent Lord Fife over to Paris on purpose to ascertain this important fact. His Lordship was a constant visitor to the salon, in company with a French danseuse, upon whom he spent £40,000 in a short time. Another visitor was Fox (not the celebrated Charles James), the Secretary of the British Embassy. He was never seen by daylight, except at the Embassy or in bed. At night he rushed to the salon, and if he had a Napoleon it was sure to be staked and lost. At last he was successful. He put down all he had, won eleven times in succession, broke the bank, and carried off 60,000 francs. Gronow calling upon him a few days after found his room filled with silks, shawls, bonnets, shoes, laces, and the like. “It is the only means I had,” Fox said, in explanation, “to prevent those rascals at the salon from winning back my money.” Lord Thanet was one of the most inveterate gamblers. He had an income of £50,000, all of which he dissipated at play. When the tables were closed for the night he would invite those who remained behind to stay and play in private. One night he lost £120,000, and when told that there had probably been cheating, simply replied, “Then I consider myself lucky in not having lost twice that sum.” A great gambler of the day was the Hungarian Count Hunyadi. He was for a time the rage, on account of his good looks, manners, and wealth. Ladies’ cloaks and cooks’ dishes were a la Huniade. For a while his luck seemed invincible; at one time his winnings were reckoned to amount to two million francs. He had two gens d’armes to wait upon him to his home, to guard against robbery. To all outward appearance he was the most impassive of players. He would sit apparently unmoved, his right hand in the breast of his coat while thousands were at stake on the turn of a card or a die. But his valet said that in the morning bloody marks were to be seen upon his chest, showing how he had pressed the nails into his flesh in the agony of an unsuccessful turn of fortune. Luck turned at last, and he lost not only his winnings but his fortune, and he was obliged to borrow £50 to carry him home to Hungary. Old Marshal Blucher was a constant frequenter of the salon. He generally managed to lose all the money he had about him, and all that his servant, who was wailing in the ante-chamber, carried. When he lost he would scowl fiercely at the croupier, and swear in German at every thing French. If he won the first coup he would allow it to remain on the table, but when reminded by the croupier that the bank was not responsible for more than 10,000 francs, he would roar like a lion, and swear in his own language like a trooper. The Bank of France was once called upon to furnish him with several thousand pounds, which, it was said, were to make up his losses at play. This, with other instances of extortion, led to the removal of the Marshal from Paris by the order of the King of Prussia.

Gronow mentions three or four successful gamblers. Among these were Lord Robert Spencer and General Fitzpatrick; being nearly “cleaned out,” they put their funds together and set up a faro bank in the club, with the consent of the members. The bank, as usual, was the winner, and Lord Robert soon found himself in possession of £100,000. He pocketed his gains, and never gambled again. Still more lucky was General Scott, the father-in-law of George Canning and the Duke of Portland. He was a famous whist-player, and was careful to avoid those indulgences which muddled the brains of his competitors, confining himself to chicken and toast-water; so he came to the whist-table with a clear head, and was able, according to the admiring Captain Gronow, “to win honestly the enormous sum of £200,000.” Brummell even found time, amidst the graver cares of the toilet, to do something in the way of gambling. One night he won £20,000 from George Harley Drummond. The loser was a member of the famous banking-house, and was requested by his partners to leave. They doubtless thought that the man who could take no better care of his own money was an unsafe custodian of that of others.

Editor’s Note: To understand the fabulous sums that were gambled during the Regency at establishments like Almack’s, one most remember: one British pound in 1830 would have the purchasing power of about 67 British pounds today. Thus, General Scott’s winnings of 200,000 pounds would be worth about 13.4 million in our money, and Fox lost a similar sum playing in one 22-hour stretch.

As someone who knows little of this era but who has read a lot of Trollope, it certainly seems that gambling destroyed as many young men (and often their families along with them) as any other vice of the age.