Birds of the Air, by David Yezzi, Carnegie Mellon University Press, Pittsburgh, PA, 2013

Lord Byron’s Foot, by George Green, St. Augustine’s Press, South Bend, IN, 2012

Shadows and Gifts, by Quincy R. Lehr, Barefoot Muse Press, 2013

Oldest Mortal Myth, by Joanna Pearson, Story Line Press, West Chester, PA, 2012

* * *

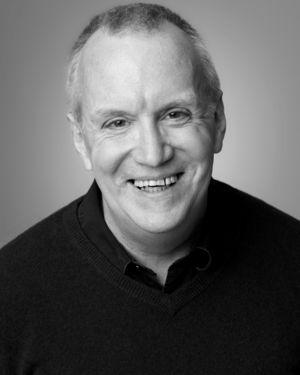

Birds of the Air

David Yezzi

Carnegie Mellon University Press, Pittsburgh, PA, 2013

David Yezzi’s third full collection, Birds of the Air, extends and expands on his previous work, making it clear that he has learned well from Auden, Hecht, and Wilbur. The characteristics that set his poems apart are the delicacy of his ear and his ability to modulate Frost’s “sound of sense” from line to line. Whereas many so-called formalists beat the snare drum, Yezzi proceeds with the lightest of touches and the keenest sense of fine-tuned emotion. “Crane” is about folding a sheet of paper into an origami bird, and more:

Paper creased is

with a touch

made less by half,

reduced as muchagain by a second

fold—so the wish

to press our designs

can diminishwhat we hold.

The lines move with extreme efficiency from a description of folding a piece of paper to a moral realization, played through the folding metaphor, that when we pursue “our designs” we often “diminish what we hold.” The use of “diminish” here is brilliantly double. It indicates that the paper is made smaller when refined into the shape of a crane, but it also suggests that the rigors of art require that something be lost so that something else, more prefect, might be gained, “something finer / and finally more.”

Yezzi’s poise and fluency play against a dark, troubled vision of life in which he—all of us—are in a precarious state, “ascending with no tether.” The gulls in his title poem, relying on the beneficence of a woman throwing bread to them in the nighttime sleet, snatch “their staple needs straight from the air, the sky replete with every wanted thing, / until it seems that they might live off giving.” The bounty of bread thrown to them, however, is soon gone, after which the gulls are ominously on their own:

After she goes, the dark birds settle back.

They float south with the floes along the bank,

their fortune pitched in wind, the water black.

It’s the menacing, unstated subtext here, as in other poems, that reveals the influence of Hecht on Yezzi’s vision.

In Part II of the new book is a sonnet sequence called “Flatirons” about climbing the peculiar rock formation that goes by this name in Colorado. It’s a meditation, affected through action, on ascent, loss and mortality as the climber goes impossibly higher, realizing that “no way looks right, and there is no way down / but keeping on.” It can be read, too, as stoic thinking on the attenuation of relationships, even with those we love:

Free-solo: dearest, I am losing you,

not now (one hopes!) but slowly, over time.

Admit that there is nothing left to do

but re-devote our efforts to the climb . . .

Yezzi has the stylistic qualifications to be considered a salon poet. I think, though, that he would cringe as this suggestion because he’s more rugged and has more fresh air in him than most. He’s earned his outdoor stripes with “Flatirons” and the stunning earlier sequence “Azores,” about sailing across the Atlantic. Rare are the poets, in my experience, who can write about po-biz and the North Atlantic and who know enough about cliffs to ask, “What is it that wipes the rock free of direction?” He writes about extreme physical situations in exquisitely controlled language. This skill is refreshing as it is uncommon.

Yezzi has the stylistic qualifications to be considered a salon poet. I think, though, that he would cringe as this suggestion because he’s more rugged and has more fresh air in him than most. He’s earned his outdoor stripes with “Flatirons” and the stunning earlier sequence “Azores,” about sailing across the Atlantic. Rare are the poets, in my experience, who can write about po-biz and the North Atlantic and who know enough about cliffs to ask, “What is it that wipes the rock free of direction?” He writes about extreme physical situations in exquisitely controlled language. This skill is refreshing as it is uncommon.

Two long, notable poems in the collection are the blank-verse narratives “Dirty Dan” (written in memory of the poet and science-fiction novelist Tom Disch) and “Tomorrow and Tomorrow.” In both of these, Yezzi lets himself relax into the colloquial registers. Here is a troupe of young actors (from “Tomorrow and Tomorrow”) rehearsing Macbeth in suboptimal conditions:

Before we left, we froze our asses off:

rehearsing in some empty public school

on 6th and B—no heat and no hot water,

when people slept in tents in Tompkins Square.

Kids would throw M-80s off the roofs—

these huge explosions—and we’d have to run for it.

We’d step outside to smoke a cigarette,

and they’d come streaming down like, holy shit!

Yezzi doesn’t shy away from emotional realism. Three poems, each in couplets, take up the vagaries of friendship and contingent alliances without a shred of sentimentality. In “Cough,” he admits scathingly:

Once you become a cliché, I can hate you—

or, treat me tenderly and let me date you.But that only retards the writing-off

That comes with boredom, amour-propre, or (cough)irreconcilable differences . . .

And in “Pals,” he notes bitingly that:

Pals find means to fit your ends,

but how long they stay pals dependson the ways you are simpatico.

How do they know? Pals know. They know.

Despite the darkness and severe elegance in Yezzi’s work, there is a sense of humor: “I feel as pointless as a garden gnome.” Anyone who can come up with a line like that has my vote. This is a great book.

* * *

Oldest Mortal Myth

Joanna Pearson

Story Line Press, West Chester, PA, 2012

Joanna Pearson begins her four-part book, Oldest Mortal Myth, by revisiting a series of ancient myths that she moves comfortably through, depicting “those / who metamorphose / for cloaked purposes / yet still take the shapes, / the dark prerogatives, of gods.” She contrasts the mythic rape of Leda with an actual act, and we see from the start that there will be difficult things about bodies in this book. In other poems from Part I, we meet Hephaestus and Pasiphaë and the terrifying but pitiful Minotaur lurking in his cannibalistic mess:

He bears his heavy cow head

above shivering human knees

and mollusk-soft genitals . . .It’s no wonder he’s bitter

in that stained labyrinth littered

with dry bones, the stench

rising from blood-matted fur,

animal-heat misting from his nostrils.

He hates as one can only hate

when others are repulsed.

The Athenian youths are sent,

bedewed and draped in terror,

and his halfling heart beats faster.

They scream at his approach.

He grunts, distressed again,

then devours them—

but watch with what slow tenderness

he pauses, dismembering

each lovely, sweet-fleshed woman.

This is very evocative writing, and the poems in Part I are successful because of her empathy with characters from Greek mythology, her ability to quicken them on the page and her fine formal control of the line as she improvises on a basic iambic beat. If the whole book devoted itself to myths, however, it could be slow going, but Pearson is too smart an artist. The book morphs, in stages, from Greek myth through Catholicism to circus folk in their sideshow misery, and from there to the medical student’s dissecting table and the hospital Emergency Room. By the time you get into Part III of the book you start to understand the unforced way these poems are talking to each other. All of them are about bodies and the terrible things that happen to them. They are raped, stolen, abused, transformed, deformed, born defective, injured, killed, dissected. Because Pearson takes great care in depicting the sad, shocking details, these poems are as convincing as they are grotesque.

This is very evocative writing, and the poems in Part I are successful because of her empathy with characters from Greek mythology, her ability to quicken them on the page and her fine formal control of the line as she improvises on a basic iambic beat. If the whole book devoted itself to myths, however, it could be slow going, but Pearson is too smart an artist. The book morphs, in stages, from Greek myth through Catholicism to circus folk in their sideshow misery, and from there to the medical student’s dissecting table and the hospital Emergency Room. By the time you get into Part III of the book you start to understand the unforced way these poems are talking to each other. All of them are about bodies and the terrible things that happen to them. They are raped, stolen, abused, transformed, deformed, born defective, injured, killed, dissected. Because Pearson takes great care in depicting the sad, shocking details, these poems are as convincing as they are grotesque.

The circus crew from Part II are the saddest of all, like “The Half Lady,” all torso, who is hated by her jealous colleagues for the beauty of her upper half as she “leaves to play roulette with Lizard Boy,” or the put-upon juggler’s wife, who lives “inside the house of shattered things.” The wives of these performers, be it the wife of the sword swallower, or the ice sculptor or the knife-thrower, lose their husbands to odd, unworthy obsessions. The circus poems risk becoming simple caricatures, but she saves them by teasing out the strangest, most awful details.

Pearson’s descriptive powers are formidable. In “The Shooter,” she describes a young man in the ER who mistakenly shot off one of his own testicles with a handgun:

The testicle, unshucked and glistening,

makes us wince but loses mystery,

a blood-streaked white against the dark skin

of this wild-eyed, weirdly silent kid.

The urology house-staff inspect “the testicle spilled out like oyster meat, / primordial, exposed, and slippery…” and “prepare to sew it back into its purse / of scrotal skin.” She describes a blood-sucking tick buried in the flesh as an “oft-missed punctuation mark / of buggish nightmare sentences, bringer of the dark / caesura, king creeper, lord crawler.”

In “Anatomy,” from Part III, she looks with her unsentimental doctor’s eye on the cadaver:

How peaceful, pickled bodies under tarps,

and so much less disturbing than we thought

to slice gray rind, to peel the stringy fascia,

to trace out nerves in arms as stiff as branches.

Each chest, preserved, is rubbery as latex.

The now-slack buttocks bunch, acquire the texture

of dank, pocked, day-old orange peels in dumpsters . . .

Welcome to the morgue! Also in Part III is a sonnet sequence, written with great invention, on various strange medical conditions: Palinospia, Prosopagnosia, and Akinetopsia, among others. Each is about the body gone awry. Part IV begins with a poem about a mother who gives birth to conjoined twins:

I bore them like I bore an underwater urn

planted inside me, raining my own tears

onto the moonscape of my belly

for them to listen. The half-shells

of their lids stayed shut, blind to my plush reds.

And when finally the doctor wrenched

them out, sleek bluish fish, I saw

translucent brows furrow, how they cast

only one misshapen shadow, and I wanted them

unhinged, cast off, thrown back.

These conjoined twins don’t make it, but they point back to their surviving counterparts in one of the circus poems from Part II. After all the gruesome problems and accidents, you might ask what exactly is the oldest mortal myth? Pearson tells us at the end of “Anatomy.” It’s “that oldest mortal myth of permanence through words.”

* * *

Lord Byron’s Foot

George Green

St. Augustine’s Press, South Bend, IN, 2012

If George Green’s mind were a room, it would be furnished with comfortable old couches, a big bookshelf (Byron, Auden, Yeats, Edgar Allan Poe, the autobiography of Keith Richards), a portrait of Maria Callas and John Wayne, a poster of Bob Dylan, a potted tree and a lava lamp. Before venturing any analysis, let me admit that my heart was softened immediately by this poem about Andy Warhol’s portrait of Mick Jagger:

He is in my opinion past his prime

already in this print, and he and Keith

are fast becoming tacky little skanks

and sherry-slurping, chicken-headed whores.

They shake their butts and sweat in leather pants,

Like ancient drag queens high on Angel dust.

Nice blank verse, George! Maybe it’s my tired mind, but I can’t help hearing in the background, “The worlds revolve like ancient women / Gathering fuel if vacant lots.” Or how about this irreverent nugget from the same sequence (“Warhol’s Portraits”), about Chairman Mao:

The Chairman’s constipation was so bad,

he only defecated once a week,

and during the Long March his weekly voidings

were sometimes celebrated by his troops.

Mao moved his bowels once on a mountaintop

above the clouds, and members of his staff

began to dance and clap their hands.

If Green is not part of some New York School, he should be. He knows a lot about painting, music, movies, opera, theater, history, literature and rock n’ roll, and he ingeniously puts all this to his own, special music. He writes about paintings and painters with the same unworried approach as Frank O’Hara (though Green favors blank verse), and he revels in the minutiae of the New York cityscape. He writes, with a great flare for camp, about the movies (Edward Field was an influence here), and he blithely cherry-picks odd things to write about from history, much the way Ezra Pound did. When you open his award-winning first book, Lord Byron’s Foot (winner of the 2012 New Criterion Poetry Prize), you’re in Green’s world.

If Green is not part of some New York School, he should be. He knows a lot about painting, music, movies, opera, theater, history, literature and rock n’ roll, and he ingeniously puts all this to his own, special music. He writes about paintings and painters with the same unworried approach as Frank O’Hara (though Green favors blank verse), and he revels in the minutiae of the New York cityscape. He writes, with a great flare for camp, about the movies (Edward Field was an influence here), and he blithely cherry-picks odd things to write about from history, much the way Ezra Pound did. When you open his award-winning first book, Lord Byron’s Foot (winner of the 2012 New Criterion Poetry Prize), you’re in Green’s world.

It may be that he has composed two of the funniest poems ever written, “Bangladesh” and his title poem, “Lord Byron’s Foot.” At the West Chester Poetry Conference last June, I witnessed Green read the latter to a packed house. I saw respectable people and estimable, middle-age poets bent over, wheezing, unable to sit up in their chairs, brought to the brink of tears. The poem is about Lord Byron and his friggin’ foot. Both “Bangladesh” and “Lord Byron’s Foot” are long, their effects cumulative, so I can’t quote the poems in full, but here are two excerpts. These things sell themselves:

from “Lord Byron’s Foot”

We see you posing with your catamite,

a GQ fashion-spread from 1812,

but one shoe seems to differ from the other.

Is that the shoe that hides your hobbled foot?

Your foot, your foot, your game and gimping foot,

your halt and hobbled, clumped and clopping foot.

In this except from “Bangladesh,” the park is Tompkins Square Park in the East Village, where Green has lived for many years:

We have to start in 1965,

when all the gay meth heads couldn’t decide

which one they most adored, Callas or Dylan,

both of them skinny as thermometers,

posing like sylphs in tight black turtlenecks.

Then, gradually, a multitude of Dylansbegan to fill the park, croaking like frogs,

strumming guitars, blowing harmonicas,

hundreds and hundreds, several to a bench . . .

Green casts his aspersions with a smile. Those who are out of favor might be called “odious poltroons” or “dunderheaded dolts.” Not everything, though, is fun and games. He also turns seriously to the helpless and forsaken, like Rose Poe (sister of Edgar Allan), a literate but toothless wreck who, after the fall of Richmond, “skulked around the homeless camps / alone, avoiding other indigents / (whom she disdained as her inferiors)… ” One recurring theme that complicates and darkens the prevailing humor is that of disappointment. We see Rita Hayworth, in “Affair in Trinidad,” as a stiffened alcoholic and smoker; the actor Jeffery Hunter, John Wayne’s sidekick in The Searchers, forgotten and depressed, “banished to foreign features” and dead at 43 after falling down a flight of stairs; and the ageing Tarzan played by Johnny Weissmuller, “the only jungle lord who really mattered” going flabby in the chest: “Sadly his middle age waxed sore on him, // causing his pecs to flap after he jumped / onto a branch, and so they put him in / a shirt and made him Jungle Jim.”

Green likes “to mess, theatrically, with craziness” but also with sadness. In the room of his mind, why the lava lamp? Because many of these poems are poems of nostalgia, for “xylophonists and ventriloquists / who lived in cheap hotels… / well used to heavy seas.” Why the potted tree? Because all of these poems are alive.

* * *

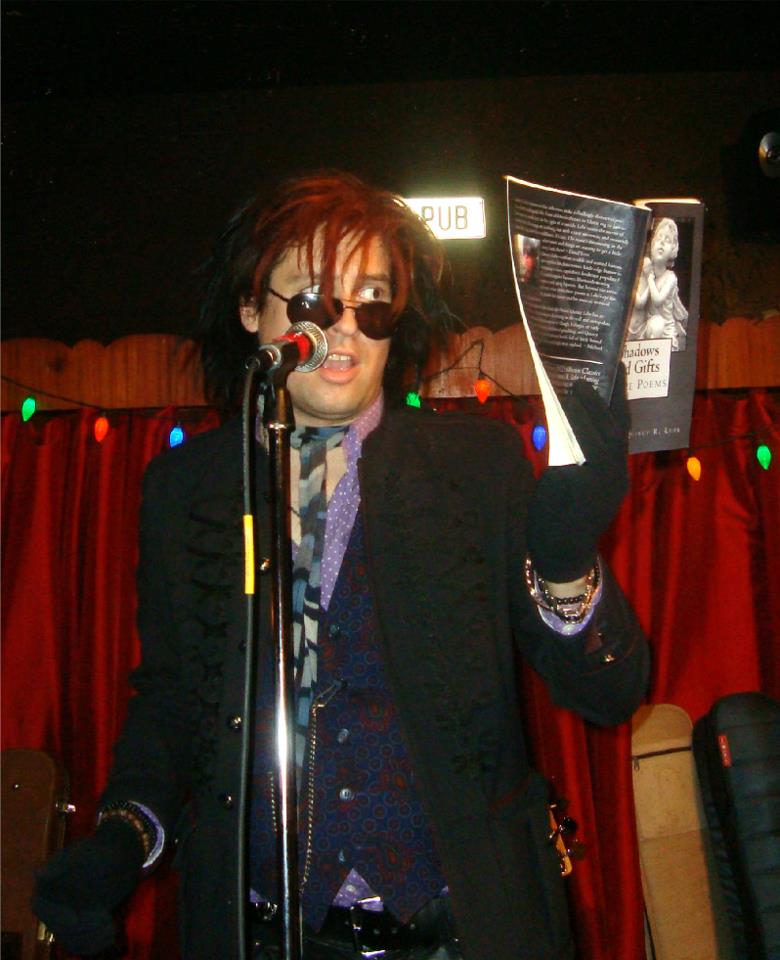

Shadows and Gifts

Quincy R. Lehr

Barefoot Muse Press, 2013

What I like most in Quincy Lehr’s poetry is the purity of his anger, his bile, and his disillusionment. If you have a pretty balloon and it’s filled with hot air, Lehr will come around dressed like a bass player in punk rock band and pop your balloon with a knitting needle. He’s not afraid of stepping forward and declaring, in well-structured verse, what he thinks has missed the mark. Lehr takes us to task not so much to pour salt in our wounds but to shock us back to some more accurate sense of where things stand, which isn’t always pretty:

You can take this any way you like,

just take it—medicine, an unpaid tax,

the clenched-up bully’s fist about to strike.

The blow will come; just take it and relax . . .

Lest one think that he is just a pugilist, Lehr is also trained as an historian (Ph.D. from Columbia). A Lehr poem is often a cry against the absurdities of history, a “desperate lunge” at the contradictions of a world in which we stagger from one cultural extreme to another:

It’s Deutschland, Deutschland, Über Alles,

and Let’s Give Peace a Chance!

Send Panzers to the Vistula

then do a hippie dance.

He’s been described as a satirist. “The purpose of satire,” as Robert Graves said, “is to destroy whatever is overblown, faded, and dull.” Lehr does that, but it’s not that simple. There is in Lehr’s poems a Romantic sensibility and even a thwarted religious impulse. So much anger and fury cannot come forth if the poet hadn’t earlier fallen from some far height where he’d once imagined things to be much better than they actually are. As he says, we have “veered from an early goal / and that thing they called ‘soul’.” I think it’s in his bitter disillusionment that Lehr finds his muse.

He’s been described as a satirist. “The purpose of satire,” as Robert Graves said, “is to destroy whatever is overblown, faded, and dull.” Lehr does that, but it’s not that simple. There is in Lehr’s poems a Romantic sensibility and even a thwarted religious impulse. So much anger and fury cannot come forth if the poet hadn’t earlier fallen from some far height where he’d once imagined things to be much better than they actually are. As he says, we have “veered from an early goal / and that thing they called ‘soul’.” I think it’s in his bitter disillusionment that Lehr finds his muse.

The concluding poem in the book, “A Gifted Child,” is a five-part satirical narrative about the disenchantment of an aspiring leftist intellectual. She is successfully launched by her old-school Marxist family into an American university. Lehr comments on the shortcomings of her lecture-hall perspective:

The ghetto residents, just blocks away,

are poor and quiet bereft

of what goes on within those walls.

“But I’m Aesthetic Left! [she says]

I do my bit with words and photographs,

with papers and critique.

I’d stay and chat, but I’m afraid

I’ve got an exam next week.”

As he tracks her fall, Lehr remarks of the futilities of post-modernist academic thought:

. . . Where the hell’s the radical other now?

Shirking its duties as the dialectic

negates its own negation in the waste,

a matter of politics—or is it taste?

The bloom comes off the rose as the student realizes in the mounting tedium of academic colloquia that “All seminars are ‘critical,’ / and every text ‘transgresses’.” She wins a fellowship and goes abroad, to Paris, to “find herself.” Instead, well . . . you’ll have to read the poem.

The Romantic speaks out when Lehr refers to “the skinny dreamer [who] turns into a fighter” and asks, “Where’ve our tortured artists gone?” This is a rhetorical question because Lehr knows where they’ve gone. After he poses the question, he turns his flame-thrower on the commercial makeover of Time Square:

Farewell, Adult Emporium! You’re now a clothing store,

maybe a Planet Hollywood—and God knows which sucks more.Where’s my filthy city gone? They smothered it in bleach,

hired a doorman, raised the rent, and placed it out of reach.

Lehr says it himself, “there’s fury in the verse.” Indeed! These poems are shot through with the ire of a punk rock ethos. Yes, Lehr has played bass in a post-punk band called Black Statues. And he’s on speaking terms with the ghosts of punk romantics like Sid Vicious. But he knows his T.S. Eliot too. Lehr is a poet of erudition and anger. In the middle poem of this manuscript, called “Who Killed Bambi,” he employs an epigraph quoting the Sex Pistols song “Pretty Vacant,” which he then brings into alignment with Eliot’s “The Hollow Men,” working off the syntax and repetition from Eliot’s cry of despair:

Somewhere between the gesture and the grasp,

somewhere between the titty and the asp,

somewhere between the cigarette and cancer,

somewhere between the pikeman and the lancer . . .

Let me conclude with one more observation about Lehr’s impressive range. The first poem in the chapbook is called “The Lengthened Shadow of a Man,” a phrase he borrows from Emerson by way of Eliot’s poem “Sweeney Erect.” In this poem, Quincy pairs the Latin poet Catullus with Syd Barrett, the doomed and afflicted founding member of Pink Floyd who was rendered dysfunctional by mental illness and drug abuse. This sort of juxtaposition is pure Quincy Lehr. Rock on!