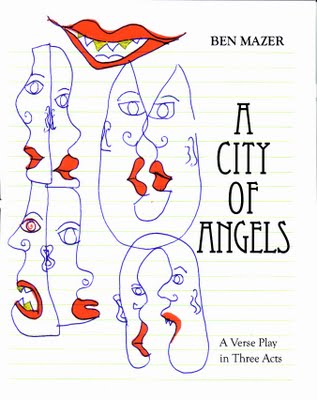

Reviewed: A City of Angels: A Verse Play in Three Acts by Ben Mazer. Cy Gist Press, 2011

Reviewed: A City of Angels: A Verse Play in Three Acts by Ben Mazer. Cy Gist Press, 2011

A verse drama—particularly when encountered, not on stage, but in a limited edition chapbook—has a tall order in front of it. It must, solely through dialogue, convey scene, emotion, and plot, even while working as verse. Ben Mazer’s City of Angels never succeeds more than intermittently at any of these. One can sense, as if through the fog of the streets in which the play is set, a far better work, but too often, one feels that an early draft has been published that is still in need of a good gust of air to clear away the mist and make the story clearer.

It’s not as if Mazer’s a novice and the shortcomings of the play can be traced to inexperience. He has three full-length collections to his credit (the two most recent having appeared in 2010), not to mention two chapbooks, editorial work with the poems of John Crowe Ransom, Landis Everson, and Frederick Goddard Tuckerman, and a position on the editorial board of Fulcrum. He has been at the poetry game a long time with no small bit of success, which makes the play’s failures all the more frustrating.

One of the dangers of blank verse, the dominant verse form in the play, is that an author can coast on a cadence—the way a hippie jam band spins out a twelve-bar pattern for twenty minutes. The first scene, which consists of a three-page monologue by one of the main characters, John Crick, has too many passages like this:

The streets are static yet they seem to move

with an unanchored motion through the grooves

of time and memory, a wider thought

that reassures them they exist in space

and that God’s nature grants they are a place

where much is predicated to unfold

when in the morning I unleash the thoughts

that brought me to return as if to break

the patterns of the time that came before

and sever all connections to the past

when time moves forward into a new day,

and motion stirs in the awakening town

to find that all is new, a blank slate

where history will properly begin

groping to find its new identity

innocently as it looks around

to find that all is moving toward now

and there is nothing that will be the same

except the streets, the sidewalks and the trees,

the houses where this change has taken place

when all emerges from its winter sleep.

I quote the third sentence of Crick’s first speech for a reason. This is a 157-word, twenty-one-line sentence, chock full of good tropes and intriguing images, none of which particularly helps the reader figure out what’s going on. A sense of mystery about whatever important business has brought Crick back to the unnamed city where the play is set is, of course, legitimate at the outset, but three pages of this stuff has a lulling effect that, rather than causing the level of tension to rise, causes the reader’s attention to wander. Not good for Act One, Scene One.

Soon enough, Crick meets Mary Wells, the daughter of the president of the local university, in which Crick, longwindedly as is his want, explains that Mary’s father has invited him to work at the university while pursuing his own, still-nebulous ideas. Here, the dialogue, which if nothing else flowed during Crick’s monologue, becomes stilted. Here’s a typical exchange:

CRICK

You needn’t trouble. I’ll sleep anywhere.

Perhaps this sofa, or the floor will do.

MARY

Nonsense. I’ll make you up a proper bed.

There is no need for you to take the floor.

We have a spare room. You’ll be cozy there.

I’ll get some sheets, and find a pillow, too.

The gaseousness of the lines becomes more irksome when one realizes that one has reached the end of the first act with very little sense of the characters. Crick is a restless intellect who has been away for a long time but is back. Mary is a bit restless, repeatedly telling Crick how quiet the town is and telling him about a disquieting, rather heavy-handedly foreshadowing dream she had about a strange man who “spoke to me as if he knew my thoughts/and offered to assist me to escape/and find my way back home.”

In Act Two, we belatedly start to get a better sense of what’s going on, as Crick tells Mary’s father, President Wells, that:

…I’d like to find a group

of young, ambitious, imaginative folk

who had some classic education but

were forward looking in their view of things

and interested in the invention of

a livelier expression than I’ve seen

on any stage in London or New York.

After all the secrecy in Act One, the revelation comes as a bit of a let-down. I was gunning for Crick being the inventor of some massively destructive weapon (especially as the play is set in Europe in 1938), and what we have instead is an artistic visionary, whom the Wellses—despite son Robert’s misgivings that Crick “sounds a little crazy”—decide to back in his endeavors (a bit too easily—the decision is almost instantaneous). Meanwhile, Crick, due to a chance meeting with one John Cross and a subsequent discussion with two old women, discovers that his family has been involved in a long blood feud with the Crosses. (One of the old women, describing the ancient feud, delivers the play’s worst line—“Many a Crick was nailed upon a Cross.”) Mary and Crick, at the conclusion of the exposition of the Crick-Cross feud, declare themselves in love with one another.

You with me so far? We are about two-thirds of the way through, and we have more or less set up the essential background information, though with all of the hemming and hawing that it has taken to get there, this reader’s attention span has been so sorely taxed that he is less moved than relieved that something seemed to be happening. Whereas in the first act, Mazer’s pace flagged, in the second act—almost as if to make up for it—the reader gets a great deal of exposition too quickly.

The third act moves the action (such as it has been) forward a month and starts in a barn where two members of the Cross family, Sam and Tom, plot to kill Crick. They, unlike their better-educated relative John whom we encountered earlier, not only hate the Cricks but, in Tom’s case, artsy-fartsy intellectuals whom literary magazines praise. Clearly, both hatreds would apply to John Crick. Obviously, Mazer sees two themes come together, as he has Tom Cross complain (after a series of godawful puns like “Do You be Cross?” and “one shit Crick up our ass”):

They have gatherings of the students in the libraries where this sort of thing is read and discussed. But that’s not where things are really happening, no. There are foolish people in high positions of power who have influence over public opinion. It is a problem for literary people. But you and I don’t care for all that. Our eyes are in a sharper focus.

Mine, on the other hand, are not. We’ve been told that the Crosses are ne’er-do-wells who killed John Crick’s father, but we know this through the monologues of third parties—aside from John Cross, this is the first time we’ve actually encountered apparently typical representatives of the family. One also wonders why Tom, whom Mazer crudely sets up as a philistine, cares what the eggheads think of Crick’s (still undescribed!) drama. For Mazer, the link between Crick’s vaguely theatrical ambitions and his noble, embattled line are clear, but I can’t say the same for me.

Perhaps inevitably, Tom and Sam Cross’s attempted murder of John Crick, in which John Cross and Robert Wells die defending him, happens off-stage, described in flashback by President Wells as he languishes, dying of heartbreak. Crick learns that his is, in fact, the royal line of somewhere or other, and he and Mary decide to wed, among other things—and I couldn’t care less.

The play feels woefully incomplete, with an overstuffed plot despite nothing especially exciting happening where we can see it. The pacing is off, and Mazer, at times, seems to be uncertain what the play is about. Initially, it seems it is about Crick and his artistic vision, while by the end, it has become a tale of a blood feud and Crick’s family history. The shift, rather than drawing the reader further into the story, leaves one unmoored and unsure what the play is about, and what’s more, bored with the whole thing. While there is a good story buried somewhere in A City of Angels, at present, there are simply too many loose ends and pat resolutions. Crick’s vague, unexplained, supposedly outlandish ideas too quickly become the subject of critical raves without struggle or even specificity. The European setting on the eve of World War II only makes a few allusive appearances. And far too much of the play is consumed with characters talking with each other nebulously about things happening elsewhere, or at different times, rather than engaging in much discernible action. Mazer can do—and has done—far better than this.