(The first in a series on obscure authors and their work.)

As Reviewed By: Garrick Davis

The Count Jean-Marie-Mathias-Philippe-Auguste de Villiers de l’Isle-Adam was born in 1838, and it is not extravagant to assert that his destiny was determined by his birth. He was the last heir of one of the great noble families of France, whose lineage could be traced back to the Crusades. Among his ancestors were the highest officials of the ancient kingdom; the greatest of them was Philippe, the Grand Master of the Order of the Knights of St. John of Jerusalem, and Founder of the Order of the Knights of Malta, who defended the Isle of Rhodes against Suliman’s armies in 1521. The family coat of arms was gold on a field of blue, with a severed arm draped with an ermine banner and its mottoes seemed fashioned for the poet: “Va oultre!” and “La main à l’oeuvre.”

[private]More importantly, he was the only child of the Marquis de l’Isle-Adam. The poet’s cousin and biographer, the Vicomte Robert du Pontavice de Heussey, has written: “I do not believe that there has ever existed either in reality or in fiction a character more extraordinary than that of the father of Villiers.” The stories of this thin and imperious gentleman have almost passed into legend; one fable should suffice to sketch him here. The family lived modestly in a small village in Brittany and, to support them, the Marquis looked for buried treasure by digging near the old family castle near Quintin. Why? He was convinced, and persuaded his son as well, that a fortune had been hidden by their ancestors during the Revolution. The gold was never found, of course, but to the end of his days the Marquis schemed for that lost wealth. “Papa is continually on the point of becoming a millionaire,” the poet once remarked, “and I like him a lot despite this formidable quirk.”

Thus Villiers was born into an inheritance of dreams. His family was “at the same time exceedingly well-born and excessively poor.” His father was impractical to the point of madness; his mother was merely kind and pious, and believed that her son would restore the family name to its former glory. As the fiscal irrationality of the Marquis continually threatened to bankrupt the household, Villiers’ mother demanded a legal separation five years after her son’s birth. This was granted in the same year that Villiers’ maternal great aunt, Danièle Kerinou, saved the family by adopting it. With the women firmly in control of the purse-strings, the Marquis was rendered an eccentric but no longer ruinous presence. All of them henceforth lived together, on the aunt’s modest retirement pension, and continued to do so for another twenty-five years, until her death in 1871.

The only point on which such a family could agree was that Villiers was a genius. In grade school, he raised baby birds in his desk and wrote long stories. At seventeen, he wrote poems for a lovely Breton girl who died suddenly, and conceived the ideas for novels and plays that consumed him for the rest of his life. It was the boast of his cousin and biographer that Villiers’ memory “was so good that he knew by heart almost everything he had ever written.” As his novels, poems, and plays have been collected into eleven volumes, this is a terrifying claim. He possessed a photographic memory, as we now call it, and not just for his own writings. Friends and acquaintances have attested that Villiers was known to recite, in artistic gatherings, some of the longest of Poe’s novellas in their entirety.

Memory alone was not what made his name. His conversation was brilliant-indeed, it was probably his greatest gift-a soaring and labyrinthine gale that dazed his listeners. Joris Karl Huysmans rated him the greatest talker of his day, along with his fellow poet Barbey d’Aurevilly. The American critic James Huneker, who met both of these writers in Paris when he was a struggling teenaged pianist, rated Villiers even higher:

My French poet was naturally neat, charming in his manner, and the most wonderful talker in the world. Barbey d’Aurevilly could discourse with the magic tongue of a lost archangel; but Barbey, with all his coloured volubility, could not improvise for you entire stories, books, plays, during an evening in a hot, crowded, clattering café. These miracles were nightly performed by my poor dear friend. How did he do it? I do not know. He was a genius, and lived somewhere in the rue des Martyrs.

This in the year 1879, when Villiers was forty years old. As a youth, he already possessed this gift of improvising monologues by the yard and it was merely by talking, casually, that he was to become famous throughout Paris, shortly after his arrival.

It was twenty years before the meeting with Hunecker, in 1859, that Villiers and his family permanently moved to Paris. Such were his abilities that the family encouraged him unceasingly in his artistic vocation and, once he had determined to become a writer, they sold everything and followed him to the capitol. They had resolved “to go and await in some out-of-the-way corner in the formidable town the final victory of the last of the Villiers de l’Isle-Adam, who, according to their childlike faith, was with brain and pen to reconquer for them the fortune and the celebrity which their ancestors had won by blood and sword!” Rarely have parents shown a greater dedication to the dreams of their child, and Villiers, for his part, was dedicated to them entirely. Indeed, it was the great burden of his life to realize his family’s ambitions for him, and that he failed to do so undoubtedly weighed on him far more than the indifference of the reading public to his work. These failures were, however, unforeseen as yet. On the day that the family began its march to Paris, the old Marquis was said to have shouted, “It is God’s will!”

Coming to the capitol, Villiers searched out the writers he most admired. He presented himself at the offices of the Revue Fantaisiste, the journal of young French writers who were soon to be called, derisively, “Parnassians”-after the title of the group’s anthology. The revue was headed by the nineteen-year old Catulle Mendès, and through its offices passed many of the distinguished artists of the day. This was, in fact, the great age of French literature. Hugo, Balzac, Baudelaire, Gautier, Flaubert, Musset, Heredia, Verlaine, Sainte-Beauve, Vigny, Nerval, Dumas, Leconte de Lisle, the Goncourts-all of them walked the streets of Paris in these years, and Villiers was accepted by them immediately. “He impressed us, “said one observer, “as being the most magnificently gifted young man of his generation.”

It was here, in the rooms of the Revue Fantaisiste, off the Passage Mirès, that Villiers met Charles Baudelaire for the first time; it was to be one of the most significant friendships of Villiers’ life. It was also Baudelaire who introduced him to one of his artistic heroes, Richard Wagner. Many nights he drifted through Paris with Wagner and Baudelaire on either shoulder, discussing art. It was also here, in 1864, that he met Mallarmé, who remained his best friend to the end of his life.

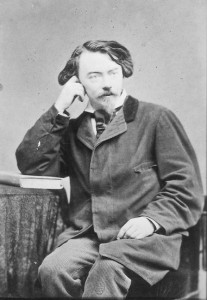

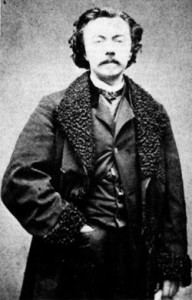

The young Villiers was difficult to miss in any crowd. He would walk into a room, with his fair hair curled into locks, wearing a fur-lined coat, and an enormous Cross of Malta around his neck. When telling his stories, he often mimicked his imaginary characters, in the style of a great and original actor. He kept all of his manuscripts near at hand-in fact, stuffed in his coat pockets-so that he could work on them when the mood struck. When caught without paper, he was known to write on anything; some of his poems are preserved on cigarette sheaves, on napkins stained with beer from the ale-houses, and wine from the cafés. Mallarmé said that this was the particular form of his dandyism, his special sign-manuscripts in his pockets, always.

The early promise of Villiers never settled into popular success or, even, regular publication. Though his Premières Poésies were published soon after he came to Paris, it was rare that any press took the risk of printing him. His first few books were all set to type at his expense. Many of his plays were accepted by theater managers but never performed, just as many of his stories were taken by newspaper editors but never printed. When his work did appear, it was in such tiny editions that he was thought a fraud by some because his books were almost impossible to find. Villiers was not entirely blameless in his obscurity. He would constantly announce commissions, imminent publications, and completed works that have never been found, and were probably never written.

Yet he was never motivated by the worldly success that his family craved for him, going so far as to state that “an individual who writes for fame is not worthy…to be given a job as a nark in a properly-run police station.” Fame he did not seek, but public notoriety came his way in spectacular fashion in 1863. The throne of Greece was empty, and the protectorate nations of England, France, and Russia were to decide on its next king. Napoleon III was understood to hold the decisive vote. Villiers’ father came home one day, visibly agitated, and read the following announcement in the paper:

We learn on good authority that a new candidature has just been announced for the throne of Greece. The candidate this time is a French grand seigneur well known all over Paris-the Comte Philippe Auguste de Villiers de l’Isle-Adam….At the emperor’s last private reception, one of his intimates having inquired concerning the probability of this candidate’s success, his majesty smiled enigmatically. The new aspirant to kingly honours has our best wishes.

Villiers took the news seriously from the first, and set about preparing for a royal reception. The Marquis, believing his son in need of only money to complete his rise to monarchy, went out to beg from the Baron Rothschild and disappeared for a week. Meanwhile, Villiers requested an audience with the Emperor. This was duly granted-the message being delivered, by an Imperial carriage, to the door of the family’s house on the Rue St. Honoré. A tailor was found who provided the young count with gloves and evening coat, on credit. On the appointed day, a hired carriage took him to the Tuileries where he encountered the Duc de Bassano, the acting chamberlain of the palace. Convinced that the Duc wanted to eliminate him from contention for the throne, Villiers refused to speak to anyone other than the Emperor; meanwhile, the Duc took the writer for a lunatic and promptly had him forcibly removed from the chamber.

Why had Villiers been granted an audience at all? “Because the Emperor believes everything he reads in the newspapers,” according to the writer, “just like everyone else.” In fact, according to his cousin, Villiers had been the victim of perhaps the greatest hoax ever perpetrated by one writer on another. It was also an act of revenge.

Some time before, Villiers had pulled a prank on his colleague, Theophile Gautier, by offering the role of Othello to that great writer and critic-who also styled himself an actor. This production of Shakepeare’s play was wholly imaginary, but Villiers charmed Gautier into frequent rehearsals and, finally, into wearing a strange costume, and staining his face and arms black, for the part. At the appointed hour of the dress rehearsal, Gautier walked into a crowded café in the guise of Othello-and was greeted with the howls of his fellow artists. He was not amused, but he bided his time in order to expose his counterpart’s vain presumptions as an aristocrat.

So, in due time, when the newspaper columns began to muse on Villiers’ suitability for the Greek throne, no one suspected Gautier (a columnist and theater critic for more than one paper) of planting the rumor. After all, the lineage of Villiers de l’Isle-Adam was such that this improbable idea swiftly became possible; and the Emperor soon received letters, seconding Villiers’ nomination, from an innocent public. It was, no doubt, beyond Gautier’s wildest fantasies that his victim would actually be interviewed by the Emperor, but when Villiers received the invitation, Gautier prepared his dupe in this way:

The contriver of the trick took admirable advantage of the disposition of his victim; he reminded him that the familiars of the Tuileries were not over-scrupulous; he told him a heap of tragic anecdotes relating to the morrow of the second of December, and having as their scene this palace, which, according to him, was as full of trap-doors as an operatic stage. Many people, he insinuated, who had entered that little door on the Place du Carrousel have never been seen to come out; so let Villiers beware, for if any favourite had an interest in his disappearance, a trap-door, a dungeon, might open suddenly under his feet. Above all, he must absolutely refuse to explain himself to any but the emperor himself!

Sure dire warnings did not fail to affect Villiers, for he wrote his will and sent it to his uncle just before leaving for the palace. Once there, his rudeness toward the chamberlain ruined what must have been a legitimate interview for the Greek throne! To the end of his days, Villiers believed that he had been a candidate-as, indeed, he had-and that no hoax had taken place; also, he insisted that the Duc had wished to destroy him that night but “my coldness, my dignity, the good style and moderation of my words, doubtless impressed the Sbirri, and I was allowed to depart in peace.” For his part, Gautier did not admit to the prank-as well he shouldn’t-since his ploy had deceived not only Villiers but the Emperor, and most of France as well, and he probably feared for his life should the truth be told. His jest had, after all, nearly made a penniless poet the King of Greece! Thus ended one of the most improbable episodes in all of French literary history.

There were more mundane disappointments waiting for Villiers as well. In 1866, he proposed to Théophile Gautier’s younger daughter, Estelle, only for his parents to refuse the match as beneath him. He duly broke it off. A year later, he founded the Revue des Lettres et des Arts and filled it with fine contributors; it lasted six months. During the winter, Villiers waited desperately for the printer to deliver a few hundred copies of the latest issue; when they arrived, he made a bonfire of them to heat his rooms. He applied for a literary grant only for his dossier to be returned to him with one word scrawled near his name: “unknown.”

The worst years, however, arrived with war. Though he was a Royalist and a Roman-Catholic, Villiers remained in Paris during the Commune. He even manned the barricades, and fought alongside the Communards-in his own eccentric way, of course. Calling himself “Captain of the Waifs and Strays of La Villette”, he walked about in a strange uniform of his own creation, with the insignia of a branch of some imaginary guard. He always had a mania for wearing huge medals and decorations at ceremonial occasions but, now, glittering rows of them were found beneath his overcoat. One wag dared to ask him who conferred such honors. Villiers’ reply was curt: “I do.”

This was 1871. The conditions in Paris were almost insufferable, and the shadow of starvation faced all of those who remained in the city. It is said that rat’s meat and horse flesh were sold in the markets at prices most could not afford. It was in this year that Aunt Kerinou died-and this was the great tragedy from which the family never recovered. With her passing, the stable income from her pension disappeared. The apartment on Rue St. Honoré was abandoned quickly; the furniture was sold; Villiers’ mother returned to the country. His father would not be put off from his speculations concerning some bitumen lakes and continued his adventures, now quite penniless. And Villiers “went to live alone, to begin that sad pilgrimage through Parisian lodging-houses, which lasted all his life, and closed in the Rue Oudinot, under the roof of the Brotherhood of St. Jean de Dieu.” He was thirty-three.

In 1879 the young Huneker met Villiers, now forty years old, in the Café Guerbois; he has left us a wonderful transcription of this evening, entitled “The Magic Lantern” and collected in his book, The Pathos of Distance. How had Villiers spent those years? Hunecker describes the Bohemian life that the Frenchman suffered, and the ill fortune that had already become synonymous with his name:

That he barely managed to make ends meet we knew; we also knew that he never sold any of his stories or novels or plays. True, he seldom wrote them. He only talked them, and the prowling animals of Bohemian journalism, sniffing the feast of good things, would pay for the drinks, and later the poet had the pleasure of reading his stolen ideas, in a mediocre setting, filling some cheap journal. How he reproached the malefactors. How he reproached them in that passionate, trembling baritone of his. No matter, he always returned to the café, drank with the crew, and told other tales that were as haunting.

Villiers was neither a drunk nor an idler. He was a night-owl, and preferred the evenings for his walks, which often lasted until dawn. This perambulatory life was probably begun to avoid creditors, and the possibility of debtors’ prison, but it became his routine over the years. He composed his works while he wandered, and no one, according to his cousin, “knew all the secrets, all the hidden sores, all the grandeur, of the merciless streets of Paris” better than he. Villiers was known by the inhabitants of this garish world, but he was not one of them:

All that population of charlatans which swarms before the cafes, money-lenders, money-getters, and rogues-sham litterateurs and sham artists-journalists, venal, if not already bought, scandal-mongers, masters in the art of blackmail, stealers of other men’s ideas, well-dressed blackguards, elegantly apparelled demi-mondaines, swindlers…he unmasked them all in short, sharp, vengeful sentences, burning with implacable scorn.

The outcasts and misfits of Paris often returned his sarcasm by bowing before him, in mockery, and calling him “the nobleman of the soup kitchens.” It may be said that the great vice of Villiers was pride-particularly in his lineage and his name. The world, certainly, did all it could to humble him for it. Though he was dressed in filthy clothes, often broke, and hungry-he was proud,

…and with a lively sentiment for the illustrious name he bore, he would never, when poverty came upon him, undertake any of those lucrative, if ignoble jobs, which in these days were always to be had in the literary world. He carried his respect for his calling as far as his respect for his ancestry, and no matter how pressing his need was, he would never send a hastily-finished page, nor even sentence, to the printer. He read and re-read everything, first low, then loud, and finally, when the whole was weeded and corrected, he would declaim it in that clear sonorous voice which he always used when reciting his own writings. According to him, the worst crime a writer can commit is to sell himself.

This was not madness but, rather, the extreme fastidiousness displayed by the finest artists in all ages-which the world never understands, and rarely recompenses. That Villiers was able to maintain his artistic standards throughout his life, in the face of such adversity, is a testament-not to pride but to faith. He possessed an integrity which pride alone cannot sustain, unless it is supported by faith in the highest degree. It cannot be an accident that his last lodgings were found on the Street of Martyrs.

1879 was a schizophrenic year. At the invitation of Wagner, Villiers managed to travel to Beyreuth, where he was presented to the King of Bavaria. At Wagner’s insistence, Villiers read one of his tales to the assembled court, and was astonished at the laughter he incited. It was only after the Grand Duke of Saxe-Weimar, who later became the Czar of Russia, pointed out Liszt nearby that Villiers understood: the court was astonished at the resemblance of the pianist to Villiers’ imaginary character, the Dr. Triboulat Bonhomet. His reading was a great success, and Villiers was treated as a great writer in Germany, which must have struck him with the greatest irony when he considered his position in his own country. He met Nietszche at Wagner’s house, enjoyed the musical concerts, and then returned home.

That same year, Villiers moved to a “tenth-rate” room in the Rue des Martyrs, where his faithful friend, Léon Dierx, lived next door and his cousin nearby. Pursued by creditors, he now lived “on the heights of Montmartre, where he still possessed an old easy-chair, a rickety table, and a poor asthmatic piano, which the bailiffs had despised.” It was here, as well, that Villiers first met the woman who would later become his wife, Marie Dantine. She was a retired midwife who became devoted to the writer, and looked after him as best she could. When Villiers was asleep, Marie would sneak into his room and mend his garments, or replace a ruined shirt with one donated by his cousin. The building’s waiter was even trained to bring in a bowl of soup, very quietly, for the writer around noon. The man who had once retained the Comte de Houssaye to find him a bride from the rich nobility was now domesticated by an illiterate charwoman, who bore him a son out-of-wedlock in 1881. Villiers cherished this young heir, but refused to marry the mother-out of shame, perhaps, or fear of disappointing his parents.

For the Marquis and his wife were still alive, residing in a shabby apartment on the Avenue Malakoff. Whenever Villiers sold a story, he would rush to his mother and share the proceeds. She, too, remained devoted to him until her death in 1882. To obscure her passing in one of the poorest districts of Paris, Villiers wrote a letter to the newspapers extolling her family’s lineage and listing their ancient titles. The Marquis himself passed three years later.

Thus, his parents hardly lived to see the worldly success of their son-modest as it was. He became a regular contributor to Le Figaro, and found it easier to place his work in various publications. His fame was further enhanced when Joris Karl Huysmans published a novel, A Rebours, in 1884 which caused a sensation in the literary world. The main character of this book, Des Esseintes, spoke of Villier’s work in glowing terms, and book sales increased. The two men became close friends, and Villiers would dine with Huysmans on Sundays, accompanied by young Victor. He also befriended Leon Bloy, and maintained his close relations with Mallarmé, who held the older man in the highest esteem.

The next years were triumphant but all too brief. In 1886, the publication of his longest work, L’eve future, was greeted with astonishment and critical praise. A Belgian society offered to pay him handsomely for a series of lectures, and, incredibly, he obliged. He managed to afford a better apartment, abandoned his usual lodging-houses, and installed a few pieces of cherished furniture bequeathed to him by his parents. He was no longer consigned to the direst poverty. His books were sold and discussed. He possessed a son-who would carry on the family name, and on whom he lavished his attention. In 1888, Villiers fell ill. Huysmans will tell us the rest:

Sickness prostrated him, laid him shivering in his bed. Weary of Paris, he settled at Nogent, and soon grew worse. Dr. Robin recognized the symptoms of cancer, but disguised the truth, asserting that the malady was one of the digestive organs, and fortunately Villiers believed him. One day that he was suffering more than usual, the sick man complained to me about the house he was in. It was, as a matter of fact, as cold as a cellar, sunless, almost rotted with damp. He said he would like to leave it, and added that he needed skilful nurses to turn and move him in his bed. I mentioned the Brothers of St. Jean de Dieu in the Rue Oudinot in Paris, and two days later I had a letter from him saying he was settled in their house….I found him there delighted with the change, convinced of his speedy recovery, full of plans, amongst others to give up going to the brasseries on the boulevards and to work quietly in some corner far from the buzz of journalism.

Villiers began at this time to talk about ‘Axël,’ which was then on the stocks, and which he desired to remodel….And then suddenly he grew silent. For the first time, perhaps, in his life, that gift of fancy, which had enabled him to forget all the endless sufferings of life in the fairyland of his imagination, failed him. He beheld life as it really is, understood that cruel reality was about to wreak her vengeance on him, and then his long martyrdom began.

Villiers was soon unable to eat. Newspaper reporters came daily to the monks, inquiring whether the famous writer had died yet: they were impatiently awaiting his departure so that they could file his obituary. Meanwhile, friends implored him to marry Marie Dentine for the sake of his illegitimate son, but he resisted and would not give his reasons. Finally, Huysmans talked to a priest, Father Sylvester, who promised to persuade the dying man as best he could. Villiers, within minutes, gave his consent. Huysmans managed to arrange the necessary paperwork, and a ceremony was conducted at the bedside. Huysmans stood as a witness and reported:

When it became necessary to sign the registers, the wife stated that she did not know how to write. There was a terrible moment of silence. Villiers lay in agony with his eyes closed. Ah! He was spared nothing. His cup overflowed with bitterness and humiliation! And while we were all looking at each other, almost broken-hearted, the wife added: ‘I can make a cross as I did for my first marriage.’ And we took her hand and helped her to make the mark…

The priest who had convinced Villiers to marry his mistress now performed a last kindness for the couple. Though it was against the rules of the Brotherly Order, he had obtained permission for the new wife to stay by her husband’s side during the night, for Villiers greatly feared that he would die alone in the darkness.

A few days later, the last sacrament was given to him. He could no longer speak, but managed to squeeze his last visitor’s hand gently. Huysmans hurried away, overcome with emotion at seeing his friend “half-conscious, his wan face grown hollow, and his throat rattling.” It was late, and the convent closed. The next morning, Huysmans’ doorbell rang, very early, and he knew, before he answered it, that his friend was gone. Villiers’ wife had come, sobbing, to bring him the news.

The aftermath of Villiers’ passing was just as tragic. There was no money for the funeral, so the editor of Le Figaro graciously supplied a sum sufficient for his decent burial. Huysmans and Mallarmé stood by the grave with young Victor, and “sheltered the poor unconscious orphan boy as best we could from the pelting rain.” The storm finally drove Leconte de Lisle away before he could finish his eulogy. As for his only son, Victor-the last heir of the noble and illustrious line of Villiers de l’Isle-Adam-he died in 1901, a childless boy of twenty.

What more can the reader bear to hear of this man’s life? For Huysmans, it was almost too painful to recall his friend and “that extraordinary existence, starving, forlorn, penniless, and clouded by troubles so great as to make his condition at times without parallel in its misery.” Mallarmé was haunted, too, by his example. When asked about Villiers, he would say, “He was the man who refused to be anything but that for which he had been born.” There was no higher praise.

His tomb is in Père Lachaise; I have stood there myself.

***

Links:

Essay by Arthur Symons (from The Symbolist Movement in Literature)

The grave in Père Lachaise of Villiers de l’Isle Adam