Of all the modern poets of France who claimed noble birth—and many did so, by inserting de before their last name as a literary and social affectation—only two indisputably had that right: Villiers de L’isle-Adam and Robert de Montesquiou. And while Villiers was born to a family of paupers who had titles but no land, Robert was to enjoy such immense wealth that his lifestyle became the stuff of legend. He was the first and last example in French literature of a new archetype: the playboy poet. Only Lord Byron occupies a similar place in terms of lineage and literature, but there the analogy abruptly ends: the two men otherwise share no similarities. Rather, it is Oscar Wilde, with his fastidious and ironic wit, that Montesquiou most resembles.

The Count Robert de Montesquiou-Fezensac was born, the last of four children, on the 7th of March in 1855. The lineage of his family made it arguably the oldest and most illustrious in France—traced back to the time of the Merovingians, through the dukes of Aquitaine. D’Artagnan, the fourth Musketeer, was an ancestor. The poet’s great grandmother had been the governess of Napoleon’s son; and the poet was dressed in the diapers of the King of Rome as an infant.

When Montesquiou was born he was put in the hands of a wet-nurse, under the immediate care and attention of his grandmother—his mother being too weak, apparently, to care for him. His father, meanwhile, was out of the country. This seemingly temporary arrangement swiftly became permanent, as Robert was shuttled from chateau to chateau—the precocious toy of his grandmothers, who traveled with an army of servants in attendance. Perhaps consequently, he was never close to his family and his later notoriety was not endearing to them. One can only imagine what Montesquiou’s relatives thought when he said of them:

Our ancestors having exhausted the spirit of the family, my father inherited only a sense of grandeur. For my brother there was nothing; but he had the courtesy to disappear. As for me, I will have the glory of adding to the ducal bonnet of the Fezensacs the laurel crown of the poet.

Though he was introduced to the influential Robert Haas earlier, Montesquiou’s true initiation into the literary world came in 1875, when he was invited to a fancy-dress ball given by the Baronness de Pouilly. Here, Robert first met the poets and writers with whom he had always wished to be intimate: Barbey d’Aurevilly, Francois Coppée, José-Maria de Heredia, and Catulle Mendès. He soon also made the acquaintance of Judith Gautier, and Stephane Mallarmé. They all noted his intellect, his amusing nature, and the sincere respect he displayed for the literary profession. Robert was soon well known among both the fashionable and literary circles of Paris.

Would he be a poet or a painter? A critic or collector? Strange to say, Montesquiou’s first great success was in the field of interior decoration. In the attic of his parent’s mansion on the Quai d’Orsay, he transformed the rooms into a kind of dandy’s heaven that transfixed and fascinated his contemporaries. Robert gave tours regularly to favored guests, several of whom left detailed descriptions of these surroundings. The furniture was even described in fashion magazines. What could have made such an impression? What did the apartment contain? It was a marvel:

[…] Leaving himself free to adorn any bare walls later on with a few drawings and paintings, he confined himself for the present to fitting up ebony bookshelves and bookcases round the greater part of the room, strewing tiger skins and blue fox furs about the floor, and installing beside a massive money-changer’s table of the fifteenth century, several deep-seated wing-armchairs and an old church lectern of wrought iron, one of those antique singing-desks on which deacons of old used to place the antiphonary and which now supported one of the weighty folios of Du Cange’s Glossarium mediae et infimae Latinatis.

The windows, with panes of bluish crackle-glass or gilded bottle-punts which shut out the view and admitted only a very dim light, were dressed with curtains cut out of old ecclesiastical stoles, whose faded gold threads were almost invisible against the dull red material.

As a finishing touch, in the center of the chimney-piece, which was likewise dressed in sumptuous silk from a Florentine dalmatic, and flanked by two Byzantine monstrances of gilded copper which had originally come from the Abbaye-au-Bois at Bièvre, there stood a magnificent triptych whose separate panels had been fashioned to resemble lace-work. This now contained, framed under glass, copied in real vellum in exquisite missal lettering and marvelously illuminated, three pieces by Baudelaire: on the right and left, the sonnets La Mort des amants and L’Ennemi, and in the middle, the prose poem bearing the English title Anywhere out of the World.

This was Montesquoui’s study, barely fictionalized by the novelist Joris-Karl Huysmans in A Rebours (or Against Nature). Published in 1884, this novel had for its hero the ultimate aesthete and dandy, the Duc Jean Floressas des Esseintes, “ a frail young man of thirty who was anaemic and highly strung” and whose resemblance to Montesquiou was purely intentional. Huysmans had heard the tale of the extraordinary apartment from Mallarmé and from the Goncourt brothers—and he reproduced the details of those rooms, and their owner, with such precision that, to this day, Montesquiou has not escaped from the shadow of his fictional twin. A Rebours caused a scandal, and it quickly became the Bible of the so-called Decadent movement. (It gained its eternal notoriety at the trial of Oscar Wilde in 1895. When asked by the prosecutor the name of the “yellow book” that so corrupted Lord Wotton in The Picture of Dorian Gray, Wilde identified A Rebours. )

Montesquiou found himself, at the age of twenty-eight, infamous—a figure that the reading public considered indistinguishable from Des Esseintes. So much so that, when the Count ordered rare books from a dealer one day, the owner exclaimed with supreme naivete: ‘Why, Sir, those are books fit for Des Essientes!” The Count was unamused. He was not the mirror image of that character— Montesquiou was never so antisocial or withdrawn. Still, the resemblances are so striking that these qualifications are quibbles. Both were consummate dandies. The fastidious attention to personal appearance, the exotic connoisseurships, the cultivation of eccentricities for their own sake, the wish to raise aristocratic living to a kind of art, the narcissism raised to self-parody—all of these characteristics marked Montesquiou as one of the most remarkable personalities France has ever produced.

Where had Montesquiou found his strange and exquisite taste? How had he arrived at such fantastic and bizarre notions? There were some famous literary and aesthetic precedents. As a young man, Baudelaire had decorated his rooms at the Hotel Lauzun in an outlandish manner, while the famous English dandy Beau Brummell had been lionized in print by the author Barbey d’Aurevilly, whom Robert admired. There was the popular icon of Lord Byron, along with the Romantic excesses that he embodied. Still, Montesquiou was to exhibit all of these strains simultaneously and in extremis: as fastidious and fashionable in high society as Brummell, as eccentric and shocking in his tastes as Baudelaire, as careful in his pursuit of art as Byron was careless in his pursuit of life. This is why Montesquiou, refracted through the lens of A Rebours, became the model hero of the Decadence—that late 19th century movement characterized by refined aestheticism, artifice, and the quest for new sensations.

He also now found himself the Arbiter Elegantiarium—the Supreme Judge of Taste—for the literary and fashionable demi-mondes of France, a position he was to occupy for several decades. Whether at the offices of Le Figaro or Charvet, he was (what one French caricaturist called) “our national Petronius.” The fashion mavens of the Faubourg St. Germain, and the wealthiest society wives, composed his inner circle on one side: Baroness Adolphe de Rothschild, Countess Potocka, Marquise de Casa-Fuerte, Princess Bibesco, along with his dearest friend and cousin, the Countess de Greffulhe. On the literary side, the Count numbered Mallarmé, Heredia, Edmond de Goncourt, Paul Bourget, Judith Gautier, and Robert Haas among his friends. He mixed these two circles together to startling effect. At one party in 1891, Gustave Moreau, Heredia, and Leconte de Lisle mixed with nobility on the island in the Bois de Boulogne, while pieces by Fauré and Wagner were performed.

The Count was not content to remain the living shadow of Des Esseintes either. He moved from his famous apartment, now imitated far and wide, and discarded much of the furnishings. His new inspiration was Japan. From visits to museum exhibitions and suggestions from Judith Gautier (who was an accomplished Orientalist), Montesquiou’s new apartment on the Rue Franklin embraced the East: a Japanese gardener was hired to tend the dwarf pines in blue pots and the lantern-studded rock garden, as the Count took tea dressed in a kimono. Whistler sketches were hung above Empire furniture. An immense beaten copper kettle supplied water for a Persian bath in the dressing room. In another room, the hydrangea flower was the single motif: the paintings and the furniture were covered with them. Many pieces were commissioned from Émile Gallé, the famous glass-maker, who considered the Count his “dear and immaculate guide” aesthetically. Gallé sent letters to Montesquiou written on strips of wood veneer or ocellated paper; in return, the artisan was sent to visit Wagner with a recommendation. Together, the pair designed a cheval-glass inlaid with wisteria, a chest of drawers decorated with hydrangeas, and a clock whose marquetry displayed pansies “to strike the mauve hour.”

Montesquiou’s affinity for all things Japanese did much to popularize the fashion. The Countess de Greffulhe installed a red lacquer bridge and a pagoda at her mansion, while the Bing store for Oriental antiquities became a way-station for wealthy collectors. Meanwhile, the Count was befriending painters: Paul Helleu, Le Gandara, John Singer Sargent, and Jacques-Émile Blanche (whose alienist father had treated the poet Gerard de Nerval with such sympathy). Together, these artists were working through the influence of Japan and, soon, of England as well. In 1884, Montesquiou traveled to London and discovered the Pre-Raphaelites, and the philosophy of William Pater. Burne-Jones took him to the studio of William Morris; and the Prince de Polignac introduced him to a newly arrived American writer, Henry James. In turn, James arranged the first meeting of Montesquiou with the painter who became his great friend and confidante, James Whistler. Temperamentally, they were brothers—the American author of The Gentle Art of Making Enemies was immediately sympathetic to the French master of the malicious maxim. In letters to each other, Whistler signed himself “The Butterfly” while Montesquiou was “The Bat.”

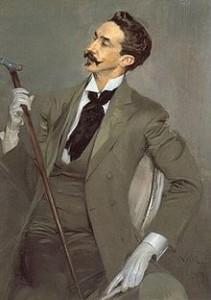

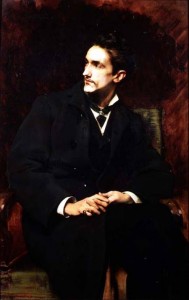

Whistler painted a dark portrait of the Count which can be seen in New York City, slowly eroding, in the Frick Museum. It was the last large canvas that Whistler ever finished. Montesquiou had it exhibited at the Salon of 1894, and held court in front of his own portrait on several occasions—publicizing Whistler’s genius. When asked by a prospective patron how much it was necessary to pay for a Whistler portrait, the Count thrusted: “One must give him more that one is able to!”

Montesquiou was now at the center of the Art Nouveau movement, as he had been the inspiration for the Decadence. Moreau, Le Gandara, Whistler, Helleu—all trusted his taste and advice. As he had once discovered and idolized Odilon Redon, the Count now championed Aubrey Beardsley. The poet and aristocrat understood, as well, the power that his taste exercised in polite society, and that knowledge no doubt turned him to aesthetic criticism. One of his epistolary titles from this time perfectly describes his new role—“the Professor of Beauty.” As an impresario of the arts, the Count would deign to please and instruct those disciples who understood the master’s call. The shift in styles from the Decadence to Art Nouveau is also illustrated in the choice of emblems on his personal stationary. The bat was abandoned for the peacock—that most flamboyant and arrogant of birds, resplendent in its polychromatic plumage.

In seeking a new style at once harder and more classical, he also discarded Japan and moved to Versailles, where a mansion on the Avenue de Paris was leased to suit his new tastes. The grandiose proportions, the perfect geometry of the gardens—the Count was so enthralled by the majesty of the Sun King that he had himself photographed as Louis XIV. His ambition was now to host the most exquisite parties. Helleu was retained to paint the fountain; his secretary Gabriel Yturri was sent to buy exotic flowers; Sarah Bernhardt was assigned the task of reciting his verses. His summer garden parties became the destination for fashionable Paris circles. The menus and the guest lists were drafted painstakingly, like poems, and mixed figures like Anatole France with Countess Potocka. A fancy dress ball was even held on the lawns of the Trianon, the guests costumed as the Royal Court—the Count began to refer to Versailles as his “marble beach.” It was in 1893, at one of these fetes that the painter Madeleine Lemaire introduced the host to one of his shy admirers: Marcel Proust.

It did not take long for this young man to ingratiate himself with Montesquiou, who desired talented disciples. Proust was soon religious in his attendance on the Count, and faithful in his service to the point of imitation; his gestures, his pose, even his laugh began to mimic his mentor. Montesquiou, for his part, shared every scandalous detail, every terrible secret of high society with his young friend, and it must have been with a mixture of bewilderment and awe that the Count encountered, some years later, his vast armory of anecdotes in Proust’s novel, only slightly concealed. The mentor had neither considered his pupil’s perfect memory, nor counted the latter’s insatiable desire for gossip and social gatherings as anything more than snobbery. Certainly, Montesquiou had not guessed that his entire milieu was to be the subject of the greatest French novelist of his day. The adulteries, bankruptcies, and degradations of the upper class that the Count regaled Proust with were meant to be enjoyed, not repeated.

Proust’s indiscretions, however, would not come to light until 1913. At the turn of the century, Montesquiou was busy exercising his genius for entertaining—the success of his parties at Versailles had merely fueled his ambition to create ever larger gatherings and richer decors. His beloved personal secretary, Gabriel Yturri, located an impressive mansion in Neuilly, near the Bois de Boulogne, that was soon renovated and named “the Pavilion of the Muses.” Sycamores were planted around the outdoor rotunda, silks were chosen to line the bedroom walls, marble statues stood in marble halls, Empire furniture filled the great salon—and, for the final touch, a pink marble fountain that had once belonged to the Sun King himself was carted from Versailles, all ten tons of it, and installed in the garden. Still, the Count’s eccentric collections were not discarded. In the library, beside the esoteric volumes, were shelved his literary relics: a bird-cage owned by Michelet, a lock of Lord Byron’s hair, Beau Brummell’s cane, Baudelaire’s sketch of his mulatto mistress. The Countess Greffulhe had even allowed a plaster cast of her chin to be made; it too had its place of honor.

Into such a magnificent setting, Montesquiou marshaled his guests with all the deliberation of a general commanding troops in the field. Some were blacklisted, some were invited to be mocked (as the host was fond of saying: “Every party should be given against someone”), while others were suffered to visit merely for the sake of their profile. The Count’s attitude to them is enlightening, especially when he considered if he had, ultimately, entertained well:

Without doubt a little despotically. The truth of the matter is that I prefer the parties themselves to the people I invite to them—and perhaps my guests realize that. I have always regarded them as an inseparable—shall I say unavoidable?—detail of any reception, but a detail that it, alas! all too often recalcitrant. Guests are a flock of sheep, not easily guided and eager to nestle in the remote corners of an apartment or the recesses of pieces of furniture, rather than stand in the position suggested to them in a well-ordered gathering…

Such was the reign of “the Lord of Transitory Things,” as Montesquiou once described himself in a poem. The choice of flowers and colors for each occasion, the careful selection and guests, the arrangement of music, from all of these details the Count created not so much a party as a living tableau—and it is a testament to his power that polite society allowed itself to be dominated in such a way for thirty years. It was a curious bargain to be sure; Montesquiou would fawn over guests only to circulate punning couplets at their expense later. Of one distinguished gentleman he rhymed:

Boni de Castellane can pass

For banker, daughter, and ass.

As for Mrs. Potter Palmer, the rich wife of a biscuit manufacturer:

Pamela bears the palm as champion biscuit-maker

On only one small point does she defy persuasion—

To eat one of her biscuits you can never make her,

Even the finest meet with obstinate evasion.

With all those who admired or detested him, Montesquiou left the impression that his tongue was chiefly to be feared. They schemed to gain his attention, flattered to procure his invitations, and purchased de luxe editions of his poetry—but he preferred to make enemies of these acolytes. One of Proust’s letters to him figured this trait superbly: “You rise above enmity, like the seagull above the storm, and you would suffer from being deprived of this upward pressure.” So this seagull was always summoning a storm in order to fly—as if controversy was the only air he could breathe. Such perversity eventually ruined his reputation, just as his desire to emulate the extravagances of the Sun King decimated his finances. In the end, the society over which he dominated as a lord and tastemaker was one that he disdained, so much so that he could declare: “Society people have no wills, they only have whims.”

The Count was now a man in his fifties. His own books, sumptuously designed, had not brought him the critical respect or the public attention that he craved. He was dismissed as a dilettante, a gifted amateur—with money and taste, to be sure, but talent? The reception he received from his fellow poets was always polite but a little cool; as for the masses, he enjoyed their warm indifference. Of all the writers that Montesquiou championed over the years, there was only one whose charms he found it impossible to impress upon the public: his own. How could his gifts as a taste-maker best be used? How could he still be of service to Literature?

It was time to think of his legacy; the Count was hopeful of finding a new disciple, a new and sublime talent, to whom he could bequeath all his adages and art, all his strategies and guile—the wisdom that had conquered and dominated fashionable Paris for thirty years—but when each acolyte appeared he was eventually rebuffed. The young Jean Cocteau, who could scarcely conceal his desire to emulate the Count, was one of those who failed to impress the older man with his brilliance. For once, Montesquiou’s eye for genius faltered—here was, after all, the one who most deserved lessons from the Professor of Beauty. Instead, Montesquiou would wave away those who attempted to introduce him to Cocteau socially by jabbing, “I know her well already.” As for Cocteau, did he not spend the rest of his life faithfully imitating the Count—albeit without the older man’s blessing?

Montesquiou was also capable of kind gestures. On one occasion, Bernhardt was induced to recite the Count’s poem in honor of Edmond de Goncourt, who followed the lines “in a copy written in Montesquiou’s hand and illuminated by Caruchet; the paper was buff, decorated with peacock’s feathers painted in gouache with so much discretion that they seemed to be no more than elegant watermarks on it.” He gave Mallarme’s doomed son a parakeet from the West Indies, in a golden Chinese cage. The sixty-six letters that Verlaine wrote to him—on hospital stationary, on the calling cards of prostitutes, on bills from wine merchants—the Count had bound in Moroccan leather with this line from Molière as epigraph: “Men and women afflicted, singing and dancing.” He also privately arranged a pension for the old poet and, when that proved insufficient, sent messengers with money. On the day that Rimbaud’s former companion perished (with the final, fevered words: “The wreaths are suffocating me…take away the wreaths”), Montesquiou visited him; he also helped pay for the funeral where so many wreaths were laid.

The Count was capable of kindness, but his life is remarkable for its bracing wit. Some of his remarks were little sarcasms that barely stung—Heredia’s stunningly beautiful and imposing wife, for example, was nicknamed “The Breasted Tower.” Others were so cutting and definitive that they became legendary. He first created and then, rather peevishly, destroyed the career of the pianist Léon Delafosse by blacklisting him with his chorus of society women. When Delafosse passed his mentor soon after their falling out, he bowed—but the reply was supremely blasphemous: “It is natural that one bows when passing the cross, but one must not expect the cross to return the bow.” Such was the end of Delafosse’s career. Montesquiou was even sharp from beyond the grave:

A last act of malice, prepared many years before, came to light shortly after the death of the Count. Madame Arman de Caillavet’s daughter-in-law, who imagined that she could tell the poet everything since she lived with the delusion that he was in love with her, had been in the habit of writing to him constantly. In his will, Montesquiou bequeathed to her a casket, which his solicitor announced that he would bring to her. The unfortunate woman summoned all her friends. ‘You see, he loved me—I am the only person to whom he has left a souvenir.’ The casket arrived in due course and with beating heart she opened it, a circle of friends round her. It contained all the letters she had ever written to him; and none of them had ever been opened.

As for Proust, the Count was almost the last to recognize him as his true literary disciple. The publication of Recherche was met with a condescending curiosity first, followed by grudging approval, and then bitter recognition. This last emotion was inevitable; though Proust denied it to Montesquiou repeatedly, the cruel homosexual dandy Baron de Charlus bore a great resemblance to the Count. “I am in bed, ill from the publication of three volumes which have bowled me over”— he confessed to a friend. The obsession with his former protégé grew until he filled a notebook with comments on the novel, and even asked one lady: “Will I be reduced to calling myself Montesproust?”

The gulf in reputation between Proust’s books and his own threw the Count into despair. His last years were devoted to insipid séances and ad hoc spiritualism. He took rest cures far from Paris, accompanied by his new secretary Pinard, but his strength would not return:

An impression which is even more extraordinary than painful is that which consists of suddenly observing, without any warning, that one’s life is over. One is still there, more or less physically dilapidated or still putting up one’s resistance, and with one’s faculties apparently intact but ill-adapted to the taste of the day; one feels disaffected, a stranger to contemporary civilization, which at one time one had anticipated, but whose present manifestations wound and shock less than they seem vain.

One of the great shocks of Montesquiou’s life was that he had lived to see himself go out of fashion; the second shock was to find that fashion had changed into something he could not understand or care about. In a sense, this was the spiritual death of the dandy and the snob. Before his relatives could complain, the last chateau at d’Artagnan was quickly sold to strangers. The rest of his belongings were bequeathed to his secretary—his collection of canes; the engravings by Whistler; the portraits by Laszlo and Helleu; William Morris tapestries and Chinese vases; gilded writing desks and ebony chests; the sublime creations commissioned from Galle and Lalique; and the 500 files that composed his correspondence and notes. Finally, there was the magnificent collection of books—those many rare volumes bound and decorated expressly for him—that made Montesquiou one of the greatest bibliophiles of his day. (They were sold and scattered at auction a year after his death; the three-volume catalog is now a collectible itself). After packing up all of his items from the Palais Rose, the Count decided to spend the winter in Menton. He lived another three weeks.

The body was brought to Versailles, where Montesquiou was buried next to his faithful Yturri. Only twenty guests attended; none were relatives. Of all the poets and painters and personalities that he had touched with his sympathy, or struck with his tongue, only one came to mourn: Ida Rubinstein. The rest had other fashions to follow. A motto was etched on the tomb (“Non est mortale quod opto”) but the best grave-marker was sketched, of course, by Proust; the day after Montesquiou’s death, this letter arrived at the residence of the Duchesse de Gramont:

[…] I got to know him at an age when I was still young enough for him always to remain for me what a ‘great personage’ is to a child. The miracle is that during a period of so many years in which I saw, one after another, so many ‘stars of the social firmament’ suddenly become ‘old bores’, viewing this transformation with the astonishment of someone who, not having been informed that summer-time started the day before, does not understand why his watch does not tally with others—the miracle is that, during all those years, there was never a cloud between us and that he would, with a smile, always allow me to reproach him with his conduct to so many people. I say no clouds, or at least not ones that I noticed; but he was not a man to conceal them and his manner was more that of one who is about to hurl a thunderbolt. However, his memoirs will put me right about that. It is not, however, possible (and up to his last weeks, in spite of his assertions to the contrary) that he was not slightly angry about the proportion, in effect radical, between the little success of my book and the frightful obscurity into which his own had fallen. It is one of the great injustices of our time, and from it he suffered terribly. He never knew all that I undertook to defeat a conspiracy of silence, for which in the beginning he had himself been perhaps in part responsible. But I nurse two hopes about him. The first: I do not believe in the literal sense of the word (and in spite of all the telegrams that he sent me last year from a nursing-home) that he is dead. Was he even really ill? In any case, if he was indeed ill, that must have given him the idea of a sham death, at which he would be present like Charles V, to surprise us afterwards. He was a brilliant stage-manager. The departure for Menton is inexplicable if he was dying; and other things too.

If, alas, the death was not feigned but true (which is what I do not believe) he will come back all the same. Injustices have their day. And at least in spirit and in truth he will be reborn.

This letter was found among a heap of kindling-paper in the house of the Duchesse by Montesquiou’s biographer, Philippe Jullian, in 1965. Such was the fate of that “inexhaustible” subject, whom Proust called “the wittiest man I have known.”