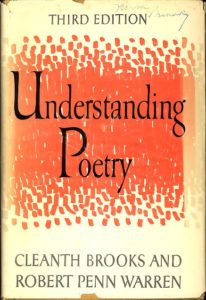

Reviewed: Understanding Poetry by Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren. 1st edition, 1938. 2nd edition, 1950. 3rd edition, 1960. 4th edition, 1976.

Reviewed: Understanding Poetry by Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren. 1st edition, 1938. 2nd edition, 1950. 3rd edition, 1960. 4th edition, 1976.

What was the most important literature textbook of the 20th century? A work by two associate professors at Louisiana State University, it turns out, which went through four editions, and which made millions for them. Understanding Poetry—which by its second edition had already been adopted by over 250 colleges and universities—is one of the great landmarks in that rite of spring, or forced march, that we call the undergraduate survey course. For more than 40 years, hapless college freshman were assigned this tome (680 pages, minimum) as their one great rope to climb the unfamiliar crags of Parnassus; the radioactive-orange cover of the fourth edition still inspires awe—or dread—among a sizeable portion of the still-living. Among professors, its reputation is even greater: the book is commonly credited with revolutionizing the teaching of literature in America.

Today, when textbooks are written by committees of hack teachers, at the behest of a publishing conglomerate, for the edification of school boards—a pablum for the public revised into gruel every few years—it seems remarkable that any textbook could rule a half-century, unopposed. What’s more remarkable is this: Understanding Poetry is certainly not the greatest achievement of either of its two authors, Cleanth Brooks and Robert Penn Warren. For the latter, his reputation as a teacher and critic is almost eclipsed by his poetry, his trophy case of Pulitzers and other prizes, and the popular success of his novel, All the King’s Men. (In 2005, the U.S. Postal Service even issued a commemorative stamp to honor the centenary of his birth.) Meanwhile, Brooks remains, for many, the ideal of the English professor. (He arrived in 1964 as the cultural attaché to the American embassy in London, just in time to call on an ailing T.S. Eliot; though, more usually, he was forced to lunch with too many people, “including the time-wasters, the narcissi, and occasionally the clinically insane.”) The pre-eminent scholar of Southern literature, his works on Faulkner remain unsurpassed; his critical books are classics; his teaching admired by students like Robert Lowell, Peter Taylor, and Hugh Kenner who themselves became famous writers. So this textbook is merely one title in a roll call of achievements that, between these lifelong friends, constitutes one of the great literary and critical collaborations of the last century.

It began auspiciously too. Brooks and Warren met as undergraduates at Vanderbilt University in 1924—a time when the legendary professor and poet John Crowe Ransom gathered students and teachers on Saturday evenings to read and discuss their own verse informally. The group (which included the poets Allen Tate, Donald Davidson, and Merrill Moore) called themselves “the Fugitives” and published a literary magazine with that name, chiefly to get their own work into print. (Warren was a member of the group, and a senior; while Brooks, being a freshman, was not.) These discussions were friendly but also intense and critical, as members offered close readings of proffered verses. It must have been a heady time to be a humanities student in Nashville; the intellectual ferment at this tiny college was considerable. The first issue of their magazine editorialized on the mood: “Official exception having been taken by the sovereign people to the mint julep, a literary phase known rather euphemistically as Southern Literature has expired, like any other stream whose source is stopped up. The demise was not untimely: among other advantages, THE FUGITIVE is enabled to come to birth in Nashville, Tennessee, under a star not entirely unsympathetic.” This was the dawn of the so-called Southern Renaissance.

Both men eventually left Nashville for graduate study elsewhere. Brooks went to Tulane but found it dull; while Warren went to UC Berkeley only to discover that his new classmates were more interested in Marx and Engels than Pound and Eliot. Both men were awarded Rhodes scholarships. When Brooks arrived at Oxford University in 1929, he found a welcome note from “Red” in his room. This is where their friendly collaborations first took shape, according to Warren:

Our characteristic topic of conversation was the opening world of poetry and poetic conversation and theory. We shared what might honestly be called a passion for poetry. I was already spending night after night trying to write poems, but his appetite was leading him into a devoted study of criticism and theory. It was Cleanth to whom I showed my midnight efforts, and from whose criticism, always offered with a graceful tentativeness, I was led more and more into the sense of the relation between theory and practice.

A few years later, as a favor to the graduate school dean (a Rhodes alum himself), the head of the English Department at Louisiana State University brought on Brooks (in 1932) and Warren (in 1934) as cut-rate lecturers. They were both surplus to requirements apparently; the department was already well-staffed. LSU had largesse to spread around, however, as the state’s governor, Huey Long, had only recently set about transforming a third-rate academic backwater into one of the largest universities in the country. Newly tripled in size (its marching band quadrupled as the first priority of the governor), the school had money available for a literary magazine as well, and the two young scholars were asked to start up the venture: so the Southern Review was founded in 1935.

While co-editing the journal was a carrot, sophomore English was the stick for both professors at LSU. What the pair discovered in their classrooms was a situation altogether dire. Though American literature had clearly established itself as a thriving force—and though literary modernism had decisively seized the salons of Europe and was led by American expatriates such as Eliot, Pound, Stein, and Hemingway—it was nowhere to be found in American universities. As late as 1936, the Harvard professor and critic Howard Mumford Jones could say that “in this country education in English literature is education in British literature.” The nation’s schools had not yet accepted the nation’s literature. Shelley, Wordsworth, and Keats presided while Whitman, Dickinson, and Melville remained personas non grata. This state of affairs was yet one more habit that we had learned from our ancestors across the pond. The tradition of neglecting contemporary and native authors for a pantheon of ancient and foreign books was not accidental but quite intentional: English Literature being an unacceptable thing to be taught to Englishmen until the year 1840 (when F. D. Maurice was the first to be named a professor in that discipline, unapologetically, at King’s College London).

Here we must allow a historical digression. The modern scholar might grunt at this point and ask: then how were the English learning English before? Or their own literature? The plain fact is that they were hardly learning English at all; the Greek and Latin classics being sufficient literature in the schools until World War I. The first book to argue for the study of the English language and its works did not appear until 1582 (Richard Mulcaster’s Elementary); the first histories of English literature appearing almost two hundred years later due to the diligence of Thomas Warton (1774) and Samuel Johnson (1779) and at the instigation of booksellers, not professors. It was Warton who apparently stirred the colleges finally to interest themselves in Spenser and the Elizabethan poets, and that was not until 1757—the first year that Warton served as the professor of poetry at Oxford. It took another century for F. D. Maurice to get his chair, and for Her Majesty’s School Inspector, Matthew Arnold, to begin including English authors as fit subjects for school exams. Broadly speaking it wasn’t until the 1850s that literature was taught in Britain with any regularity—a decent interval if one remembers that Chaucer had, by then, been dead for five centuries and authored works that proved (as Dante had done for Italian) that the vernacular need not be inferior to Latin.

That’s a long time for Chaucer’s countrymen to miss his point, but they did. One might say that English literature became reputable in the schools at exactly the time that the Middle English used by “the father of all English writers” became a fit subject for historical and philological study—the language of Middle English, mind you, not the masterpieces that were made from[with] it by Chaucer. This quasi-Germanic and pseudo-scientific method was imported wholesale to America and reigned undisturbed until the 1930s. What Brooks and Warren encountered in the colleges when they began their teaching careers was, in other words, a profession devoted to teaching anything but literature—teaching it, in the memorable jibe of F. R. Leavis, “in terms of Hamlet’s and Lamb’s personalities, Milton’s universe, Johnson’s conversation, Wordsworth’s philosophy, and Othello’s or Shelley’s private life.” What the typical professor of that era taught was a sub-department of History (facts being teachable exam-fodder), with an emphasis on Biography (the author’s and his circle), and a penchant for fuzzy, emotional uplift in the responses to the reading material.

So it was not only the curriculum and the reading lists that were outmoded: the discipline of English Literature itself seemed hopelessly retrograde. Of course, Brooks and Warren also faced the practical question of how to teach freshman to understand anything at all. Of those early days, Brooks later remarked:

Our students, many of them bright enough and certainly amiable and charming enough, had no notion of how to read a literary text. Many of them approached a Shakespeare sonnet or Keats’s ‘Ode to a Nightingale’ or Pope’s Rape of the Lock much as they would approach an ad in a Sears-Roebuck catalogue or an editorial in their local newspaper.

All of the textbooks that were available seemed old-fashioned and unsuitable. So Warren took it upon himself to write a thirty-page handout on metrics and imagery, which was first used in the spring semester of 1935. A year later, the handout had been expanded to include fiction, drama, and prose—and was printed by LSU with the title, An Approach to Literature. (The scholarly old-guard on campus, unimpressed by the book, began calling it “The Reproach to Literature.”) The book proved to be so popular that its rights were sold in 1939 to a commercial press (and it remained popular enough to see its fifth edition printed 40 years later). Brooks and Warren now knew for a certainty that they could change their profession, and that textbooks were the catalysts. They wanted to do something bigger, something for their poetry classes. They wanted to call the next book Reading Poems, and they set to work, as Warren later recalled, with a plan:

We sat down and argued out general notions and general plans for the book—only to find as work developed that we were constantly being thrown back to revise original ideas. But very early Cleanth had made a fundamental suggestion. After an introductory section of general discussion, we would get down to individual poems, and start with narrative, including folk ballads. Folk poetry has one great pedagogical advantage. It springs from a nonliterary world and some event that has some special appeal to the imagination of that world.

The seven sections of the textbook were divided by literary genres and devices, and the poets were not clumped together according to geography or birthdates. Each section had its own foreword. Almost forty poems were given “close readings” (line-by-line critical discussions) of several pages’ length, while two hundred more were included with questions and exercises attached. A glossary of poetic terms and techniques was included as well. The introduction to the book made a compelling case for why poetry is essential in our lives, but it was not written to be a manifesto of the “new criticism.” It was, rather, in the prefatory “Letter to the Teacher” that the authors announced:

This book has been conceived on the assumption that if poetry is worth teaching at all it is worth teaching as poetry. The temptation to make a substitute for the poem as the object of study is usually overpowering. The substitutes are various, but the most common ones are:

1. Paraphrase of logical and narrative content;

2. Study of biographical and historical materials;

3. Inspirational and didactic interpretation.

Of course, paraphrase may be necessary as a preliminary step in the reading of a poem, and a study of the biographical and historical background may do much to clarify interpretation; but these things should be considered as means and not as ends. And though one may consider a poem as an instance of historical or ethical documentation, the poem in itself, if literature is to be studied as literature, remains finally the object for study.

This was the official call for literature teachers across to the country to drop the scholarly pretensions of their profession, and return to literature. Though it seems a modest opening paragraph for a letter now, it was heard at the time as a rallying cry by the young, and a declaration of war by the old. John Crowe Ransom, in a review of the book, said as much: “The analyses are as much of the old poems as the new ones, and those of the old are as fresh and illuminating as those of the new; or at least, nearly. What can this mean but that criticism as it is now practiced is a new thing?”

The contents were startling too: the authors had included poems by their friends, Mark Van Doren and Allen Tate (twice); their teachers John Crowe Ransom (twice, alongside Dryden and Yeats) and Donald Davidson (in between Collins and Donne); and their favorites such as T. S Eliot (next to Andrew Marvell) and Hart Crane. Verses by W. H. Auden (b. 1907) settled alongside Shakespeare’s. Assumptions were meant to be unsettled by these proximities: what if a student found himself preferring a poem by Allen Tate to a classic one? Was Tate a classic then as well? Or was the classic merely a tag given by the dead for the dead, and constantly in need of questioning? One imagines that students were less rattled by this fearless line of thought than many of their teachers.

Literary reputations that were secure, even seemingly unassailable, were investigated; poems that were classroom staples were found to be flawed. The authors did not pull their punches with great men either. Edgar Allan Poe can be “very vague and confused,” and Percy Bysshe Shelley should be scorned for his love-swoons since “some people die very easily—they are always dying over this and that—always thinking that they are dying.” On lesser poets, they can be charmingly brutal. The authors chopped down Joyce Kilmer’s “Trees” (a poem so popular that its publishing rights kept Poetry magazine solvent for years) in four pages, with gusto from the opening: “The fact that it has been popular does not necessarily condemn it as a bad poem. But it is a bad poem.” Understanding Poetry placed the gentleman’s canon of 19th-century American writing, especially, under such harsh light that most of it was dropped from other textbooks at once. William Cullen Bryant, John Greenleaf Whittier, James Russell Lowell, Oliver Wendell Holmes, and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow: the Genteel Tradition evaporated overnight like a Cambridge fog. After quoting a poem by James Russell Lowell on the death of one of his children, the authors wrote: “We know that this poem was written by Lowell as an expression of personal grief. But this does not mean that the poem is necessarily a good one.” That was mild. Over three pages, Sidney Lanier was hammered as a sentimental poet with incoherent imagery: “The poet should have solved this difficulty of implication for the reader or should have abandoned the image. Instead, he ignored the matter, which seems to argue that he himself really was not paying much attention to the full implication of what he was doing.” So much for Lanier’s tearful tribute to his dear wife.

The Bostonian bric a brac was replaced by American originals: Walt Whitman, Emily Dickinson, and the modernists. A poem by Amy Lowell was included, and approved of, after one by Wordsworth. Ezra Pound and H. D. were yoked together, with a nod to the Imagist credo. Robert Frost got the lion’s share of the attention, with eleven poems printed in their entirety. (The poet must have crowed when he saw “After Apple-Picking” sandwiched between Milton’s “Il Penseroso” and Lord Byron’s “Ocean.”) Everywhere, the work of contemporary American poets rested comfortably alongside the classics. Brooks and Warren broke with another orthodoxy as well by including so many poets of the American South, who ordinarily would be neglected. A century after Ralph Waldo Emerson had warned his countrymen that they had “listened too long to the courtly muses of Europe” and that it was time for an exceptional literature to come forth from the free minds of an exceptional democracy, the American university at last had a textbook that treated its own poets seriously.

In his old age, Warren remembered their efforts very modestly: “In 1938 our book appeared to a small stir of praise and blame. As the years passed we certainly never felt that this was the book we had hoped to make.” Speaking for his fellow English professors, Arthur Mizener was more accurate: “For us the real revolution in critical theory . . . was heralded by the publication . . . of Understanding Poetry.” Harold B. Sween added that “Among the rank and file of university faculty in the English-speaking world, few works of this century have gained the influence” of this book. Some 73 years later, a better introduction to understanding poetry has not been produced.

Understanding Poetry is then, in a sense, part of the common culture of the educated American classes—in a country that eschews a common culture, and that forcefully resists, year after year, a common curriculum. If we list those books which every American should read, the list is rather long, but if we list those books which every American has read, the list is very short. In our high schools: Huckleberry Finn, The Great Gatsby, and Catcher in the Rye. In our colleges, Beloved. By this standard, which is the popular standard of what most students have been assigned at most universities, then the importance of Understanding Poetry becomes clear: its contents are the closest approximation to a canon of poetry that we possess. Herein are the poems which the educated American has actually read. In that regard, Brooks and Warren’s taste has stood the test of time very well, but then they were both readers of real genius. (One of his fellow LSU professors even gushed to a student that, “Brooks sees more in one line of poetry than anyone else does in the entire poem. He’s probably the world’s most profound reader of poetry.”)

To open its pages now and compare it to our new textbooks is to suffer vertigo—our educational system has fallen from a very high place. (What would the authors have made of colleges that don’t require English Literature majors, even, to take a course in Shakespeare?) What they never set down was a reason why college undergraduates should study poetry at all. In our own, more dissolute, day—when the humanities have fallen into disrepute—we have need of such reasons. We have need of teachers like Brooks and Warren again, who would explain to us why freshman should always be forced to climb the summits of literature together. If you think that textbooks are invariably dull affairs, you owe it to yourself to find this book.

Editor’s Note: This essay originally appeared in Humanities magazine, July/August 2011.

I didn’t see this essay in HUMANITIES and thus feel fortunate to have had the opportunity to read it here. I feel ever more fortunate that I was schooled by those who were committed to close reading but also, in the way Lowell taught at Harvard, brought biographical and historical context to various poets and their work. The various “-isms” and their inevitable schisms–and absurdities–had me fleeing graduate school at NYU and not returning, except for the classes with Seamus Heaney, Derek Walcott, and Helen Vendler I audited at Harvard and Boston University, and then the self-teaching that was part-and-parcel of being Seamus’s TA and a Junior Tutor at the former institution, until I entered Vermont College in the late eighties. The “-isms” have their place, certainly, but I think they are best understood in metaphoric terms and to be introduced to students only AFTER a solid background in word-for-word and line-by-line immersion in poems themselves. For then and only then can one hope to understand how a poem is put together. HOW it means.

Came to this late but agree to the enormous influence Brooks and Warren had in USA. Unfortunately many of the presuppositions they brought to the table in that book have been shaken by the tsunami of

critical though out of Europe after Brooks and Warren left the scene. Word for word line by line was replaced. Poets suffered the most,

I suspect. And now Marion Montgomery has passed away down in Crwfrod GA, the last living contact with the Tate, Ransom, Warren group. I suggest CPR dwell more extensively on these matters. Much of our collective poetic memory is in danger of being lost.